July 30th, 2024

Written by: Lisa Wooldridge

Henry Molaison was a healthy 7-year-old in 1933 when he was knocked over by a bicycle and hit his head. A few years later, he began to have seizures.1 The seizures got worse and worse until, by his late 20s, he could no longer function in his daily life. In 1953, Dr. William Beecher Scoville, his neurologist, offered a radical solution – surgically removing part of his brain. Molaison and his family agreed to give it a try. That decision would change the course of his life – and, at the same time, the course of neuroscience.

The surgery’s aftermath

In some ways, the surgery was a success. He entered the hospital with medication-resistant seizures so frequent and severe that he could not complete daily tasks, but over time Molaison’s seizures became more controlled by medication.3 By the end of his life, he had only one or two large seizures each year.3 But something else was very wrong. Henry could carry on a conversation for a bit, and scored above average on an IQ test.4 He remembered much of his life before the surgery, and he could still walk and draw. But he’d ask the same questions every few minutes. He couldn’t remember the people who took care of him in the hospital.

Molaison’s condition was a severe form of anterograde amnesia. That is, while he could briefly remember things happening to him from moment to moment, he could no longer store new long-term memories to remember years, weeks, even minutes later. For the rest of his life, Henry Molaison was stuck in time, unaware that it was passing around him.

In the 1950s, neuroscience still understood relatively little about how the brain makes and stores memories. Many researchers were therefore interested in studying Henry. To protect his privacy, researchers used only his initials in published works. Thus, Patient H.M. – one of the best-known people in neuroscience history – was born.

What did we learn from Patient H.M.?

Because of the unique nature of both his brain surgery and his abilities and disabilities after the surgery, Patient H.M. features in case studies across a wide variety of neuroscience topics. A case study is a type of research study that involves intensive examination and description of one, or only a few, people or events. Case studies are very useful when scientists and doctors are trying to understand rare conditions, or when trying to determine if some part of the body is necessary for normal functioning. While we can never make sweeping judgements about the brain from following a single person or even a handful of people, the findings from these cases can point researchers in new directions.

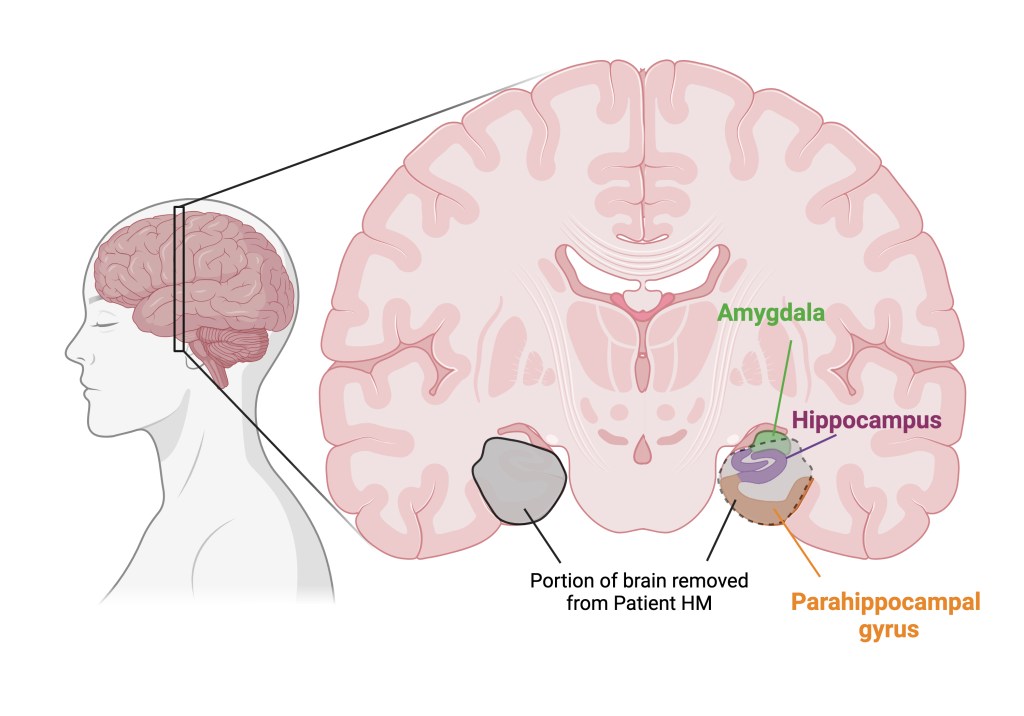

Dr. Scoville’s surgery removed a portion of Molaison’s brain containing (most of) two important brain structures: the hippocampus and amygdala. The portion removed also included a nearby structure called the parahippocampal gyrus. Figure 1 shows a map of where these structures lie in the brain and what was removed; we will discuss more about each structure’s critical functions below.2

There are dozens of case studies about Patient H.M. illustrating how these structures contribute to our experience of the world. By studying what patients without one or more of them can and cannot do, we can infer what the lost structure does, what tasks or experiences require it, and what can still happen even without it. And indeed, decades of careful research support many of the conclusions scientists initially made from studying Patient H.M. Here are just a few of the key insights we gained from that work.

Insight #1: The hippocampus is necessary to store certain types of long-term memory

Perhaps the biggest influence of Patient H.M.’s case was on our understanding of how memories are created and stored. Prior to Patient H.M.’s surgery in the 1950s, scientists were unsure how the brain produced and stored memories. The favored hypothesis suggested that memories were stored all over the cortex, the top layer of the brain that gives it its characteristic wrinkly appearance. Under this framework, different parts of the cortex were more or less of equal importance for long-term memory storage.4 But Patient H.M.’s profound memory loss after the removal of a relatively small portion of cortex – just the parahippocampal gyrus—challenged that hypothesis.

His case might also mean that memory storage didn’t rely on the cortex entirely (or at all!), but instead relied on other parts of the removed brain tissue – the hippocampus or the amygdala. By chance, Dr. Scoville had a second patient with profound amnesia (i.e., memory loss) after a surgery that included the removal of his hippocampus. Since Patient H.M. and this patient had that in common, Dr. Scoville proposed that the hippocampus was the critical brain structure for long-term memory storage.4

In the subsequent decades, an extensive body of work has strongly supported the role of the hippocampus and the nearby parahippocampal gyrus in long-term memory.1,3 To learn more about how the hippocampus creates memories, check out these articles from PennNeuroKnow authors.

Insight #2: Memories that do not require conscious thought do not require the hippocampus

When we think of memories, we tend to think about the events in our lives that we can actively remember. But, as it turns out, memory is not that simple. Though Patient H.M. couldn’t “remember” new things, he did have a different form of memory left to him – he remembered how to do things like walking or writing. He could even learn how to physically do new things – his “muscle memory” was intact. One of his most frequent researchers, Dr. Brenda Milner, taught him to draw a star while only looking at his hand in a mirror. He got better the more he did this task, indicating that something in his brain or body had remembered how to do it.3 Even six months later, Patient H.M. was still doing better at this task than when he started.

Strikingly, though he couldn’t tell you who they were or why he knew them, Patient H.M. developed feelings of familiarity with his doctors and with others he met after the surgery.3 He could learn to associate cues with outcomes – also called classical conditioning – even though he couldn’t remember learning.5 And he eventually learned the address and floor plan of a house he moved into several years after his surgery.3 Clearly, parts of his brain could “remember” – even though he was unable to tell anyone about his experience of learning these things. In other words, he could use unconscious memories, but not conscious ones.

Patient H.M.’s case indicated that these unconscious types of memories, in contrast to facts or memories about events that we can actively think of, do not require an intact hippocampus. Further work would point scientists to a completely different set of brain structures for learning and remembering skills like riding a bike, and an overlapping but distinct set of brain structures for classical conditioning.6

Insight #3: The amygdala helps us know how we’re feeling.

After some time, doctors noticed that Patient H.M. rarely complained of pain. Even when he received electric shocks during a study, he noticed the sensation but did not complain about it at all.7 Did Patient H.M. not feel these sensations as intensely as he should? Or did he simply not think they were uncomfortable?

Both were partially true. He could tell the difference between two temperatures applied to his skin, though he wasn’t as good at this as healthy subjects. This suggested that he could feel intense temperatures. However, the most striking difference came when researchers looked at his response to what should be heat-induced pain. Patient H.M. did not rate any amount of heat as painful, even at temperatures that healthy subjects couldn’t stand.7

Curiously, in the same study, the neuroscientist Dr. Brenda Milner found that Patient H.M. had difficulty rating his own hunger or thirst. When he did provide a rating, it didn’t correspond to how much he’d had to eat or drink. Together with the findings about his inability to notice pain, Dr. Milner decided he had a difficult time reflecting on how his body was feeling.

After comparing their findings to other medical and scientific reports, the researchers suggested that Patient H.M. ‘s dampened detection of pain, hunger, and thirst was probably due to the loss of his amygdala. Further research has supported this idea. In the modern day, we understand that the amygdala is important for determining whether incoming information is good or bad, and whether it’s important.8 We also know now that it is a key brain structure for responding to pain, and it helps create the characteristic discomfort that makes pain, unlike other kinds of touch, hurt.9,10 And through communication with certain parts of the cortex, we also now know that the amygdala is critical for understanding how our body feels from moment to moment (for more on this “sixth sense”, check out this previous PennNeuroKnow article).11

Conclusion

Henry Molaison probably didn’t plan to spend his life as a research subject, but his willingness to be one provided us with many insights into how the brain works. Over the course of his life, he allowed nearly 100 neuroscientists and doctors to examine him.3 Hypotheses that were first hinted at by Patient H.M.’s very specific responses to the world around him demonstrated new ideas that are now considered key principles of memory, and inspired decades of research.1 To paraphrase Dr. Suzanne Corkin, one of the researchers that worked with Patient H.M., neuroscience is in his debt.3

References

- Squire LR. The legacy of patient H.M. for neuroscience. Neuron. 2009 Jan 15;61(1):6-9. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2008.12.023. PMID: 19146808; PMCID: PMC2649674.

- Salat DH, van der Kouwe AJ, Tuch DS, Quinn BT, Fischl B, Dale AM, Corkin S. Neuroimaging H.M.: a 10-year follow-up examination. Hippocampus. 2006;16(11):936-45. doi: 10.1002/hipo.20222. PMID: 17016801.

- Corkin S. What’s new with the amnesic patient H.M.? Nat Rev Neurosci. 2002 Feb;3(2):153-60. doi: 10.1038/nrn726. PMID: 11836523.

- Scoville WB, Milner B. Loss of recent memory after bilateral hippocampal lesions. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1957 Feb;20(1):11-21. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.20.1.11. PMID: 13406589; PMCID: PMC497229.

- Woodruff-Pak DS. Eyeblink classical conditioning in H.M.: delay and trace paradigms. Behav Neurosci. 1993 Dec;107(6):911-25. doi: 10.1037//0735-7044.107.6.911. PMID: 8136067.

- Thompson RF, Kim JJ. Memory systems in the brain and localization of a memory. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1996 Nov 26;93(24):13438-44. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.24.13438. PMID: 8942954; PMCID: PMC33628.

- Hebben N, Corkin S, Eichenbaum H, Shedlack K. Diminished ability to interpret and report internal states after bilateral medial temporal resection: case H.M. Behav Neurosci. 1985 Dec;99(6):1031-9. doi: 10.1037//0735-7044.99.6.1031. PMID: 3843537.

- Janak PH, Tye KM. From circuits to behaviour in the amygdala. Nature. 2015 Jan 15;517(7534):284-92. doi: 10.1038/nature14188. PMID: 25592533; PMCID: PMC4565157.

- Neugebauer V. Amygdala pain mechanisms. Handb Exp Pharmacol. 2015;227:261-84. doi: 10.1007/978-3-662-46450-2_13. PMID: 25846623; PMCID: PMC4701385.

- Corder G, Ahanonu B, Grewe BF, Wang D, Schnitzer MJ, Scherrer G. An amygdalar neural ensemble that encodes the unpleasantness of pain. Science. 2019 Jan 18;363(6424):276-281. doi: 10.1126/science.aap8586. PMID: 30655440; PMCID: PMC6450685.

- Sun W, Ueno D, Narumoto J. Brain Neural Underpinnings of Interoception and Decision-Making in Alzheimer’s Disease: A Narrative Review. Front Neurosci. 2022 Jul 11;16:946136. doi: 10.3389/fnins.2022.946136. PMID: 35898412; PMCID: PMC9309692.

Figure 1 was created by Lisa Wooldridge using Biorender.com

Cover Photo from Pixabay.com user Jarmoluk

Is there a controversy over how much of H.M.’s hippocampus was removed? Also, isn’t it possible for hippocampal cells to regrow?

Your point #2 seems to imply a connection between memory and consciousness, but it seems H.M. wasn’t unconscious so did his state fall into some fuzzy in-between category of conscious/unconscious?

LikeLike

Hi James,

These are excellent questions!

A combination of MRI brain images decades after his surgery and postmortem examination of his brain confirmed just how much of his hippocampus was removed, but during his lifetime there was indeed a misunderstanding about how much was removed. Dr. Scoville estimated that he removed a piece of the brain approximately 8cm long each side, but the later tests showed that the removed portion was closer to 5cm. This meant that a lot more tissue remained than scientists initially assumed.

In fact, a good portion of the back part of his hippocampus remained. However, we think that it probably wasn’t very functional, since the portion of cortex removed is so important to its functioning and without it that portion of the hippocampus probably couldn’t communicate with the rest of the brain. But we don’t know for sure! (These details come from Reference 2)

You’re spot on that the brain can make new cells in the hippocampus — and it is one of the few places in the brain that does this! The total number of cells in the hippocampus doesn’t usually increase over time in humans though, instead cells are lost over time. Though they’re critical to memory, we don’t know exactly what new hippocampus brain cells are for. We also don’t know if they are able to assume the function of lost cells. And you tend to lose as many cells as you grow in the hippocampus.

Because he didn’t recover his memory abilities even after decades of surgical recovery, it seems likely that whatever new cells his hippocampus produced weren’t sufficient to replace the ones he lost. (These details come from this paper: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4394608/)

I’m not sure I would say H.M. was necessarily in an altered state of consciousness, although that depends on how you define it.

He was aware of the world around him and could engage with it — he was awake and alert, could carry on conversations for a few minutes, answer questions, etc. This probably looked like a typical level of consciousness from the outside.

Another way of stating the memory impairments: he was unable to access the types of memories that need to be intentionally recalled (like, what did you have for lunch yesterday or what is the capital of France) — i.e., ones that require conscious thought — but he had automatic memories like muscle memory and classically conditioned memories, that don’t require you to consciously think about them. So that doesn’t necessarily indicate his state of consciousness was reduced, just that he couldn’t intentionally bring up certain types of memory.

However, because the definition of consciousness often includes awareness of oneself, you could argue that he did have some impairment in consciousness because he wasn’t as able to describe his internal state as he should have been (hunger, thirst, pain).

Super long, but I hope this clears things up!

Best,

Lisa

LikeLiked by 1 person