November 18th, 2025

Written by: Lucas Tittle

Have you ever wondered how your brain decides what you like or dislike?

I started wondering this in college after getting sick from eating pizza from one of my favorite pizza places, Joe’s Pizza. I worked in a lab really close to Joe’s and I would often “forget” my lunch so that I could eat there. Once, I was late to the lab and rushed to grab a slice of cheese and scarfed it down. But then…I started to feel sick. I tried to keep working, but a few minutes later…well…let’s just say I no longer had pizza in my stomach. Since that tragic day, I haven’t eaten at Joe’s and I really don’t like it.

To be clear, I love pizza. Just not Joe’s Pizza. But how could I suddenly dislike something I once liked so much? In this post, I hope to provide insight into how the brain decides our preferences.

Emotions and actions

There is a close relationship between our emotions, memories, and actions. Each emotion has a distinct positive or negative quality, also known as valence, and the type of valence assigned to our experiences can change our perception and behavior. For example, before getting sick, Joe’s Pizza had a positive valence to me, so I associated Joe’s with something good and yummy and was motivated to keep coming back for more.1

Generating or assigning valence is something that happens in the brain, so that’s where we will look to try to answer how the brain decides our preferences.

How the brain assigns valence

The brain is made up of nerve cells called neurons, and separate parts of the brain perform different functions. However, some brain regions have multiple functions.8 For example, one part of the brain that assigns valence is the nucleus accumbens shell or NAc. People like to call the NAc the “reward center” of the brain, because it becomes active when we anticipate something we want or like.2 While this is partly true, it turns out that NAc actually participates in both positive and negative valence.2

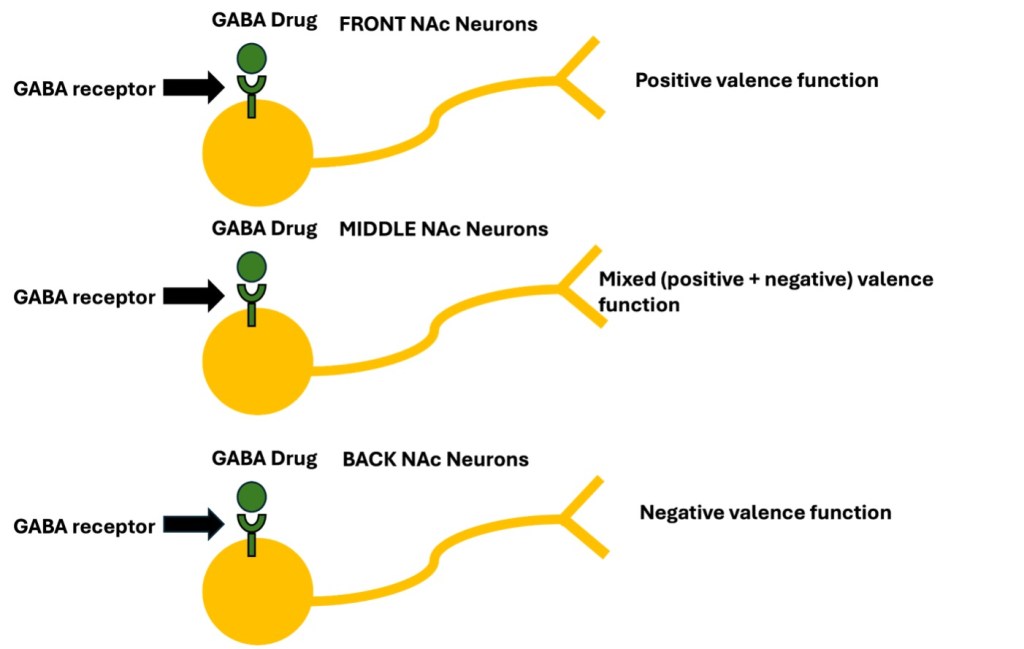

The NAc uses chemical messages, or neurotransmitters to communicate with other neurons. When neurotransmitters bind to their receptors, patterns of brain activity begin, which can start the valence-generating process in brain regions like the NAc.4 One study used a drug to activate the receptors of a neurotransmitter called GABA at different sites along the NAc. This study found that activating the front of the NAc generates positive valence and makes rats double their food intake. As GABA injections moved backwards towards the middle, the rats began exhibiting both positive and negatively valenced behaviors, and towards the back of the NAc, GABA made the rats really afraid and defensive.4

These results suggest that the NAc has separate valence-generating functions, based on where neurons become active4 (Figure 1). Similar to playing a keyboard, different notes along the NAc generate different emotional behaviors!4 But when might one emotional function happen over another in real life?

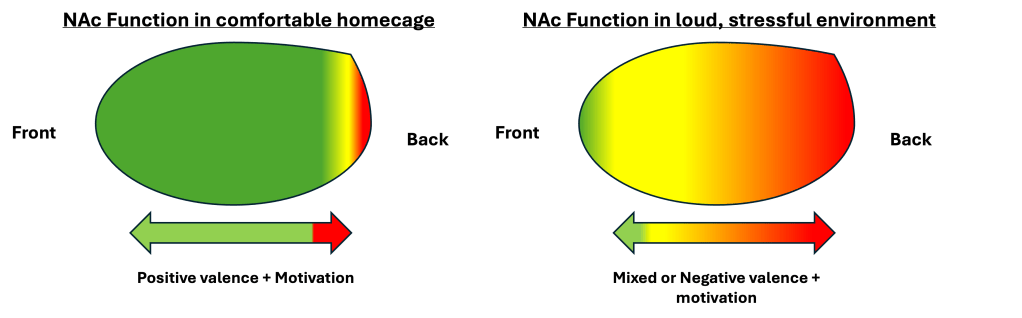

One possibility is that the NAc switches “modes” depending on the situation.8 For example, when rats are in their home cage, where they feel safe and happy, brain activity in most of the NAc generates positive valence and makes the rats increase how much they eat and drink (Figure 2). However, in a bright and loud environment, which stresses rats out, the same brain activity along the NAc causes defensive and fear-related behaviors (Figure 2). These results suggest that in stressful environments, most of the NAc switches to a negative valence mode a to alert other parts of the brain that something is wrong.5 Moreover, front-back functional divisions in the NAc may not always be dedicated to positive or negative valence functions.5,8

When good turns bad in the brain

By now, I hope I’ve convinced you that that valence is flexible, and can change depending on experience. Take my Joe’s Pizza story for example. Joe’s didn’t always have a negative valence to me. It was my negative experience with Joe’s that made my perception undergo a valence flip from positive to negative. Joe’s pizza is the exact same, but how I think of it has changed, which changed my behavior.

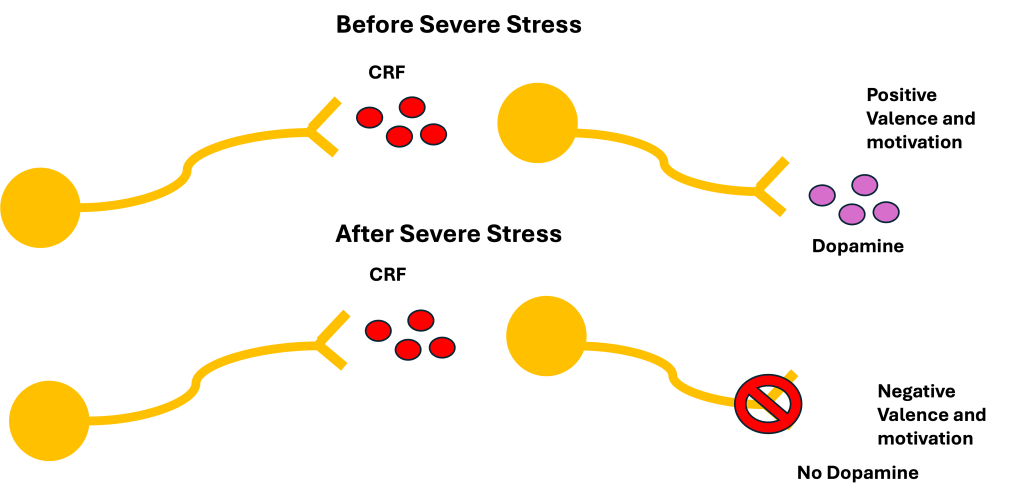

We saw before how GABA signaling in the NAc generates both positive and negative valence. However, GABA isn’t the only neurotransmitter the NAc uses. NAc neurons that use the neurotransmitter corticotropin-releasing-factor (CRF) may also be a flexible emotional mode, just over the longer-term.7 CRF is famous for being the major stress hormone that starts your fight or flight response, so it is thought of as having negative valence functions.7 However, not all stress is negative, and mounting evidence suggests that CRF signaling in the NAc generates positive valence, because CRF activity in the NAc causes nearby neurons to release dopamine, which is involved in positive valence and motivation.6,7

Since neurotransmitter signaling generates flexible emotional behaviors, the same might apply to CRF. One study found that the function of CRF in the NAc changed after a stressful experience, like making rats swim when they really don’t want to. After this “forced swim,” CRF was unable to cause dopamine release or generate a positive valence (Figure 3). This stressful experience caused another valence flip, but this time in the function of CRF in the NAc.

Conclusion

Assigning valence is an important cognitive process for several reasons. First, assigning valence is one way our brains generate meaning and decide our preferences. Secondly, flexibility in valence-generating systems can help us to adapt to our environments. However, repeated stress and adversity can disrupt this adaptive flexibility, similar to the CRF study.6 It is possible that in certain psychiatric disorders, different brain regions with multiple valence-generating modes get “stuck” in one mode or the other. Understanding how valence is generated could help the treatment of severe psychiatric disorders, and help identify the types of environments that are beneficial for emotional health.

References

- Yiming Chen, Yen-Chu Lin, Christopher A Zimmerman, Rachel A Essner, Zachary A Knight (2016) Hunger neurons drive feeding through a sustained, positive reinforcement signal eLife 5:e18640

- Pleasure Systems in the Brain

Berridge, Kent C. et al.

Neuron, Volume 86, Issue 3, 646 – 664 - Nusbaum, M., Blitz, D. & Marder, E. Functional consequences of neuropeptide and small-molecule co-transmission. Nat Rev Neurosci 18, 389–403 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1038/nrn.2017.56

- Reynolds SM, Berridge KC. Fear and feeding in the nucleus accumbens shell: rostrocaudal segregation of GABA-elicited defensive behavior versus eating behavior. J Neurosci. 2001 May 1;21(9):3261-70. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-09-03261.2001. PMID: 11312311; PMCID: PMC6762573.

- Reynolds SM, Berridge KC. Emotional environments retune the valence of appetitive versus fearful functions in nucleus accumbens. Nat Neurosci. 2008 Apr;11(4):423-5. doi: 10.1038/nn2061. Epub 2008 Mar 16. PMID: 18344996; PMCID: PMC2717027.

- Lemos JC, Wanat MJ, Smith JS, Reyes BA, Hollon NG, Van Bockstaele EJ, Chavkin C, Phillips PE. Severe stress switches CRF action in the nucleus accumbens from appetitive to aversive. Nature. 2012 Oct 18;490(7420):402-6. doi: 10.1038/nature11436. Epub 2012 Sep 19. PMID: 22992525; PMCID: PMC3475726.

- Hannah M. Baumgartner, Jay Schulkin, Kent C. Berridge. Activating Corticotropin-Releasing Factor Systems in the Nucleus Accumbens, Amygdala, and Bed Nucleus of Stria Terminalis: Incentive Motivation or Aversive Motivation?,Biological Psychiatry, Volume 89, Issue 12, 2021, Pages 1162-1175,ISSN 0006-3223, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biopsych.2021.01.007.

- Berridge, K.C. Affective valence in the brain: modules or modes?. Nat Rev Neurosci 20, 225–234 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41583-019-0122-8

Cover image by athree23 on Pixbay.

Figures created by Lucas Tittle on powerpoint.

Leave a comment