September 16th, 2025

Written by: Omer Zeliger

We’re coming up on flu season soon, which for many means coughs, fevers, and sore throats. If you catch the flu, you might feel tired and sore, end up stuck in bed for a few days, or in the worst case may develop more serious complications1. The flu, as well as countless other diseases, are caused by microscopic particles called viruses. But viruses aren’t all sneezing and sniffles. Some viruses are extremely useful for neuroscience research; in fact, the same thing that makes them so good at getting us sick is exactly what makes them so useful! To understand why, we need to take a look at what viruses are and how they normally work.

What are viruses?

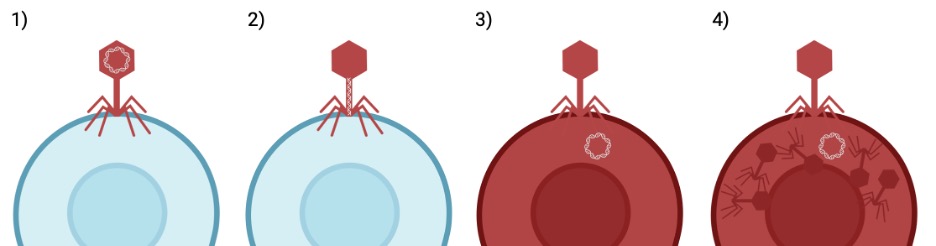

Viruses, at their core, act like nature’s gene-delivery system. The simplest viruses are made up of only two parts2. The first is their genetic material, often DNA, which contains all of the instructions to make new viruses. The second is a capsid that surrounds the genetic material, protecting it and delivering it to its destination. Unlike living organisms, viruses can’t reproduce on their own. Instead, they need to get help from host cells (Figure 1). Normally, healthy cells use DNA as blueprints to make many types of proteins, which are specialized molecules that do various jobs to keep the cell alive. When a virus finds a suitable host cell, the capsid attaches and injects the genetic material into it. Once the genetic material gets inside the host cell, the host cell treats the virus’s genes like its own. Instead of making proteins from its own DNA, the host cell begins to make the virus’s proteins. Using the virus genes as blueprints, the host cell starts to make new capsid parts and assemble more of the same type of virus. Eventually the new viruses will escape the host cell, going on to infect countless other host cells and keep the cycle going.

How does this help research?

In nature, viruses hijack host cells and trick them into using genes that aren’t originally theirs. This ability is a dream come true for researchers! If researchers can give cells new DNA, then they can control what proteins the cells create and control their function. For example, researchers discovered a protein that can turn off brain cells when light is shined on them3. By putting the gene that creates this protein into every brain cell in a particular brain area, scientists can turn that brain area off at will. They can then figure out what that brain area does by seeing how an animal’s behavior changes when the area is shut off. Recently, scientists used this method to discover that there’s a particular brain region that’s important for telling mice to eat. By silencing the brain region with this technique, they were able to show that when those cells couldn’t fire the mice wouldn’t eat4. To read more about this technique in action, check out Seeing the Light Again! The ability to give cells new genes is a game-changer for neuroscience and enables all sorts of new experiments that weren’t possible before.

Hijacking the hijacker

How do researchers use the virus’s gene-delivery ability to deliver the DNA they want? Scientists break the virus apart into its two components: the capsid and the genetic material. They keep the capsid, but throw away the genetic material and replace it with new DNA5. The virus’s capsid works like normal, detecting host cells and injecting genetic material into them. But this time, the host cells don’t make new viruses from the genetic material. Instead, they use the new genes that the researchers chose. By borrowing the virus capsid’s gene-delivery system like this, scientists gain an easy and efficient way to give host cells new genes.

Is using viruses dangerous?

Viruses are an invaluable tool in neuroscience research, but anything that causes diseases comes with risks to the people working with them. Is there any danger that these modified viruses could create new, dangerous diseases? Though there will always be a risk that scientists can get sick from the viruses they’re working with, there is a much lower chance for them to get sick from these modified viruses than from natural viruses. Viruses rely on both of their parts, the genetic material and the capsid, working together in order to replicate and cause illness. Without the virus’s original genetic material telling the host cell how to make new capsids, the host cell can no longer create new viruses and the virus cannot spread5. When scientists take appropriate safety precautions like wearing gloves and eye protection, these modified viruses are a safe and powerful research tool.

Viruses in research today

The first modified virus was created in the early 1970s6, and since then they have been used in countless neuroscience experiments. They’ve become a vital tool neuroscientists use to study how different genes affect brain activity and behavior. They’ve helped us answer a wide range of questions such as how the brain recovers after a stroke7 and what parts of the brain are involved in opioid addiction8. Today, these viruses are an indispensable part of neuroscientists’ arsenals and will continue to play critical roles in new scientific breakthroughs to understand the brain.

References

- US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2024). About Influenza. US Department of Health and Human Services. https://www.cdc.gov/flu/about/index.html

- Gelderblom, H. R. (1996). Structure and Classification of Viruses. In S. Baron (Ed.), Medical Microbiology. (4th ed.). University of Texas Medical Branch at Galveston.

- Zhang, F., Wang, L. P., Brauner, M., Liewald, J. F., Kay, K., Watzke, N., Wood, P. G., Bamberg, E., Nagel, G., Gottschalk, A., & Deisseroth, K. (2007). Multimodal fast optical interrogation of neural circuitry. Nature, 446(7136), 633–639.

- Qi, Y., Lee, N. J., Ip, C. K., Enriquez, R., Tasan, R., Zhang, L., & Herzog, H. (2023). Agrp-negative arcuate NPY neurons drive feeding under positive energy balance via altering leptin responsiveness in POMC neurons. Cell metabolism, 35(6), 979–995.e7.

- Addgene. (n.d.). Biosafety Resource Guide. https://www.addgene.org/biosafety

- Jackson, D. A., Symons, R. H., & Berg, P. (1972). Biochemical method for inserting new genetic information into DNA of Simian Virus 40: circular SV40 DNA molecules containing lambda phage genes and the galactose operon of Escherichia coli. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 69(10), 2904–2909.

- Niv, F., Keiner, S., Krishna, -, Witte, O. W., Lie, D. C., & Redecker, C. (2012). Aberrant neurogenesis after stroke: a retroviral cell labeling study. Stroke, 43(9), 2468–2475.

- Chen, R. S., Liu, J., Wang, Y. J., Ning, K., Liu, J. G., & Liu, Z. Q. (2024). Glutamatergic neurons in ventral pallidum modulate heroin addiction via epithalamic innervation in rats. Acta pharmacologica Sinica, 45(5), 945–958.

Header image by geralt via Pixabay

Figure created with Biorender.com

Leave a comment