April 8th, 2025

Written by: Jafar Bhatti

Imagine you are sitting outdoors at a café on a warm spring day. What are some of the sounds you could hear? You might hear birds chirping. Or you might hear the sound of an espresso machine whirring in the background. Or maybe you will eavesdrop on a conversation between nearby coffee drinkers. In all of these cases, you are taking in sound information from the environment, and, after some processing steps, it is sent to the brain where it is perceived as hearing.

Scientists know a lot about how we transfer sound information to the brain (for a nice summary, see Greer’s post here!) but our hearing is not always guaranteed. Hearing loss is a common phenomenon experienced by approximately 1.5 billion people worldwide, of which 430 million require treatment1,2. While the treatment of hearing loss has a long history, the more recent development of the cochlear implant has had the most profound impact. Specifically, cochlear implants have proven enormously successful in restoring functional sound and speech perception to the majority of the 1 million patients who have been implanted as of 20223. In this post, we’ll take a deep dive into the inner workings of cochlear implants and how they restore hearing.

The cochlea

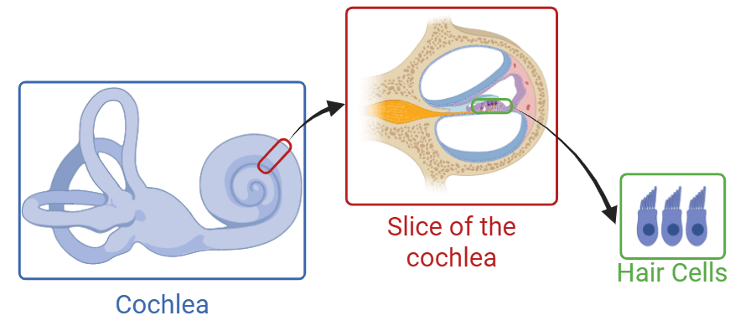

Before we can dig into how a cochlear implants works, it is important to first understand the area that is targeted – the cochlea. The cochlea is a round, spiral-shaped structure located deep inside your ear that is essential for hearing sound (Figure 1). The name ‘cochlea’ comes from the Latin word for snail shell in reference to its coiled shape. Inside of the cochlea is a long strip of tissue that follows along the coil-shaped cochlea. Location on this strip of tissue are cells known as hair cells that are responsible for sending sound signals to the brain.

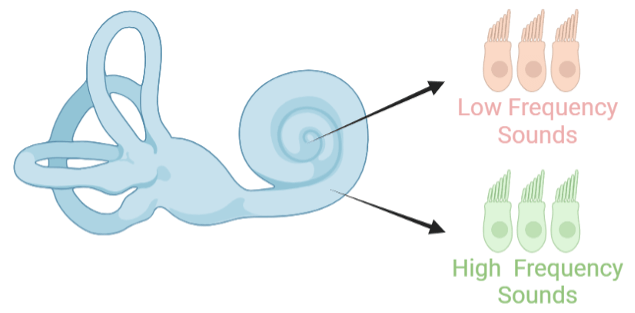

Importantly, hair cells send different kinds of sound information to the brain, depending on where the hair cell is located in the cochlea (Figure 2). Hair cells located on the outer parts of the cochlear spiral send information about high frequency sounds, like a referee blowing a whistle or a bird chirping, to the brain. Hair cells located on the inner parts of the cochlear spiral send information about low frequency sounds, like the rumble of thunder or music from a bass drum, to the brain. The sounds that we hear in our everyday lives are often a mix of high and low frequency sounds. This means that in normal hearing, lots of hair cells will be active across the cochlear, depending on the sounds we are hearing.

Hearing loss and early treatments

Now that we have an idea of how intact hearing works, we can start to imagine what happens during hearing loss. Hearing loss often arises due to damage to the hair cells in the cochlea, leading to trouble hearing in noisy environments, difficulty understanding conversations (especially with background noise), and perception of sounds as muffled or warped. What causes hair cells in the cochlea to get damaged? It varies. Hair cell damage is a natural part of the aging process. It can also occur from physical trauma to the head or overexposure to loud sounds.

The first major treatment for hearing loss dates back to the 17th century with the development of the first hearing aid, known as an ear trumpet. Since then, numerous advances have led to more sophisticated battery-powered hearing aids which often consist of a microphone (for picking up nearby sound), an amplifier (for increasing the volume of the sound), and a speaker (for projecting the louder sound into the ear). While electronic hearings aids may offer relief to individuals with mild hearing loss, they are often not effective in patients with major hearing loss.

The cochlear implant

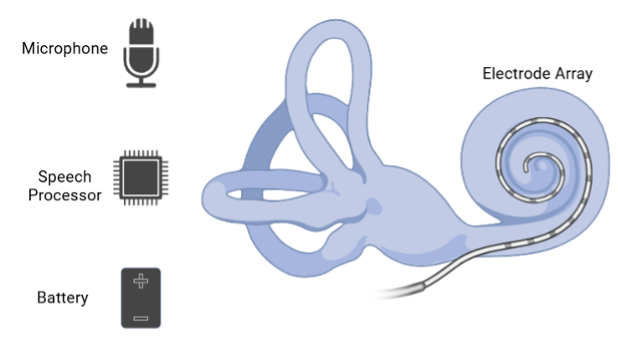

In order to restore hearing in patients with major hearing loss, the first cochlear implant system was developed in 1984. This system is similar to electrical hearing aids in that it contains a microphone and battery, but is unique in that produces the perception of sound by direct electrical stimulation of the hair cells in the cochlea (Figure 3).

First, the microphone of the cochlear implant records sound from the nearby environment. Then, the recorded sound is sent to a speech processing computer chip that breaks down the nearby sounds into the pattern of frequencies that make up the original sound. Finally, the computer chooses which contact points to turn on based on the frequencies of the original sound. For example, if the sound is made up of high frequency sounds, the computer would turn on contacts close to the outside of the cochlear spiral to stimulate high frequency hair cells. If the sound is made up of low frequency sounds, the computer would turn on contacts close the inside of the cochlear spiral to stimulate low frequency hair cells. For everyday sounds like speech, the computer would turn on electrodes at various positions along the cochlea. When the contact points are turned on, they directly electrically stimulate the hair cells which activates them and sends a sound signal to the brain. Overall, the effect of this process is the restoration of speech perception in adults with severe hearing loss.

While cochlear implants can dramatically improve hearing for those with hearing loss, it is important to recognize that not all individuals choose to have one. This is because they do not see hearing loss as a condition to be cured, but rather a way of life that can be equally fruitful as life with intact hearing.

Future Directions

Cochlear implants have undoubtedly changed the lives of individuals with hearing loss who choose to use them. Nevertheless, there is room for improvement. Patients with cochlear implants still report having difficulty understanding speech in busy or noisy backgrounds, compared to unimpaired listeners. Additionally, cochlear implants are often unable to appreciate complex sounds such as symphony music. The main reason for these limitations is that electrical stimulation of the cochlea is not specific. While the placement of the electrodes along the cochlear do allow for some specificity in regard to the frequencies that are signaled, the cochlea is full of a salty fluid and conducts electrical current on its own. This causes activation of hair cells far from the intended stimulation point and sends signals of unintended frequencies to the brain. The development of more effective cochlear implants is an active area of research. One particularly exciting avenue of research is exploring the use of light to activate hair cells, rather than electrical current. Given the success of cochlear implants thus far, research into this field is likely to promise even greater benefits to those affected by major hearing loss.

References

- The Center for Hearing Research. The University of California, Irvine. https://hearing.uci.edu/

- Deafness and Hearing Loss. World Health Organization. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/deafness-and-hearing-loss

- Zeng, FG (2022): Celebrating the one millionth cochlear implant. JASA Express Lett. Jul;2(7):077201. doi: 10.1121/10.0012825.

Cover Photo by Robin Higgins from Pixabay.com

Figures 1, 2 and 3 were generated using BioRender.com

Leave a comment