March 4th, 2025

Written by: Carris Borland

Imagine if there was a world-wide shutdown of the transport and delivery of goods. It would be chaos! We’d have empty store shelves, limited medical supplies, and less available car parts. Not to mention, it would be very frustrating for anyone eagerly waiting for a package to be delivered. Did you know that this idea of transport also applies to neurons? Neurons are special cells that help us to interact with the world (Figure 1). They communicate with each other in our nervous system to help us experience smells, taste, hugs, and great music. Supporting these tiny heroes is a vast transport network called axonal transport1, that delivers much needed supplies throughout your neurons so they can keep working all day long. Axonal transport works much like a typical transport and delivery system: you have roads, cargo trucks, shipping labels and GPS navigation. It’s so cool that neurons use the same tools as UPS to deliver their cargo! Let’s explore the role of each of these key players in the neuron delivery system and how they work together to keep the brain working.

Roads: Microtubules

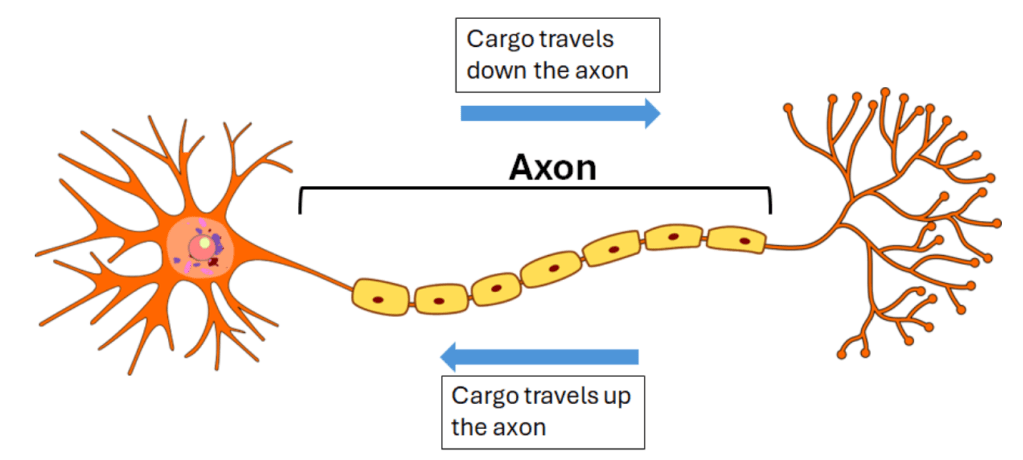

You can’t imagine not having roads- without them driving would be so much harder! Neurons have “roads” too! There are strong structures that hold up the cells called microtubules (see video 1). In a neuron, the microtubules are arranged like a two-way road: a path for cars to drive in both directions. These “roads” are important for cargo to travel both up and down the cell.

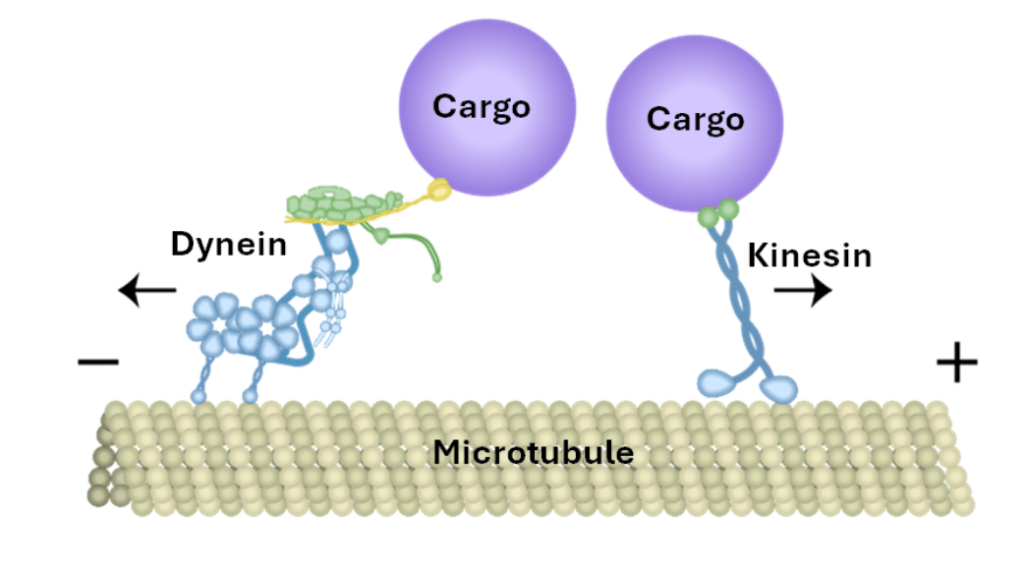

Cargo trucks: motor proteins

Just like a typical delivery system, you need trucks to take the supplies to the right place. Remarkably, neurons also have their own delivery trucks, called motor proteins. Motor proteins “walk” on the microtubule roads to transport their cargo. There are two kinds of motor proteins: kinesin and dynein3. Each “walk” in a specific direction (Figure 2). Kinesins (see video 2) are walking on the right side of the road (down the axon) while dynein (see video 3) are coming from the opposite direction on the left side of the road (up the axon).

Shipping labels: adaptor proteins

To be able to accurately deliver a package to its intended destination, we need shipping labels. Neurons use adaptor proteins as shipping labels for their cargo. These proteins attach the cargo to the right motor protein (truck) for transport 4,5.

GPS navigation: microtubule-associated proteins (MAPS)

How do motor proteins “know” when and where to transport cargo? Just like truck drivers using a GPS, motor proteins use a navigation system in the form of microtubule-associated proteins (MAPS). These MAPS interact with the microtubule (road) to direct the motor proteins on where to go 4,5. Some MAPS tell the motors to “turn left or right”, some of them tell motors to “wait”, and some tell motors to “stop and deliver here”. Aside from guiding the motor proteins, some MAPS also provide extra support for the microtubules.

What happens when your brain’s delivery system breaks down?

Just as it would be a catastrophe if there was a world-wide shutdown of transport of supplies, that would be an understatement for your neurons. There are many diseases that are linked to disruptions in parts of the delivery system in neurons. For example, tau is a MAP that supports the microtubule. In Alzheimer’s disease, the tau misbehaves and wrecks the microtubule, creating a “roadblock” for the motor proteins that prevents them from being able to transport cargo6 (Figure 3). Another example is amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS). ALS is a nervous system disease that affects movement7, and is linked to kinesin motors not working properly. There’s also Lissencephaly– a serious condition where your brain doesn’t develop properly. Lissencephaly happens when an adaptor protein for dynein isn’t working properly, so dynein doesn’t know where to go 8.

a “roadblock”.

Axonal transport is a way for neurons to get their cargo delivered to keep them happy. Just like a typical delivery system, they use roads, delivery trucks, shipping labels and GPS. When this system fails, it results in diseases. This just goes to show that axonal transport is as important for the neuron as a delivery and transport system is for our world.

References

- Guedes-Dias, P., & Holzbaur, E. L. F. (2019). Axonal transport: Driving synaptic function. Science (New York, N.Y.), 366(6462). https://doi.org/10.1126/science.aaw9997

- Baas, P. W., Deitch, J. S., Black, M. M., & Banker, G. A. (1988). Polarity orientation of microtubules in hippocampal neurons: uniformity in the axon and nonuniformity in the dendrite. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 85(21), 8335–8339. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.85.21.8335

- Goldstein, L. S., & Yang, Z. (2000). Microtubule-based transport systems in neurons: the roles of kinesins and dyneins. Annual review of neuroscience, 23, 39–71. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.neuro.23.1.39

- Maday, S., Twelvetrees, A. E., Moughamian, A. J., & Holzbaur, E. L. (2014). Axonal transport: cargo-specific mechanisms of motility and regulation. Neuron, 84(2), 292–309. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuron.2014.10.019

- Dixit, R., Ross, J. L., Goldman, Y. E., & Holzbaur, E. L. (2008). Differential regulation of dynein and kinesin motor proteins by tau. Science (New York, N.Y.), 319(5866), 1086–1089. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1152993

- Salvadores, N., Gerónimo-Olvera, C., & Court, F. A. (2020). Axonal Degeneration in AD: The Contribution of Aβ and Tau. Frontiers in aging neuroscience, 12, 581767. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnagi.2020.581767

- Soustelle, L., Aimond, F., López-Andrés, C., Brugioti, V., Raoul, C., & Layalle, S. (2023). ALS-Associated KIF5A Mutation Causes Locomotor Deficits Associated with Cytoplasmic Inclusions, Alterations of Neuromuscular Junctions, and Motor Neuron Loss. The Journal of neuroscience : the official journal of the Society for Neuroscience, 43(47), 8058–8072. https://doi.org/10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0562-23.2023

- Markus, S. M., Marzo, M. G., & McKenney, R. J. (2020). New insights into the mechanism of dynein motor regulation by lissencephaly-1. eLife, 9, e59737. https://doi.org/10.7554/eLife.59737

Cover photo by Juhele on Wikimedia Commons.

Figure 1: Image by Sanu N on Wikimedia Commons.

Figure 2: neuron image by Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 on Wikimedia Commons

Figure 3: GIF by National Institute on Aging on Wikimedia Commons or video MP4 link here

Linked video 1: The Great Exchange. “Microtubule Depolymerization.” YouTube, uploaded by The Great Exchange ,8th July 2018, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=XYZf-PYyGWA

Linked video 2: Professor Chimp. “Kinesin Motor Protein 3D Animation (with Labels).” YouTube, uploaded by

Professor Chimp, 15th February 2023, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ilgdFvit49Y

Linked video 3: Harvard Medical School. “Molecular Motor Struts Like Drunken Sailor.” YouTube, uploaded by

Harvard Medical School, 24th March 2023, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=-7AQVbrmzFw