October 16th, 2024

Written by: Jafar Bhatti

A major goal of neuroscience is to relate the activity in a particular brain area to some real-world experience, such as memory, decision-making, and physical sensation, such as pain – as we’ve explored in past PNK posts. Often what gets lost in translation when describing these exciting developments to a general audience is what we actually mean when we say, “brain activity.” Although there are numerous ways of measuring “brain activity” (which I will briefly touch on at the end of this post), most aim to capture one fundamental feature of the brain– the action potential. In this PNK post, we will take a deep dive into what the action potential is and how it can be used to represent complex real-world phenomena.

Setting the stage

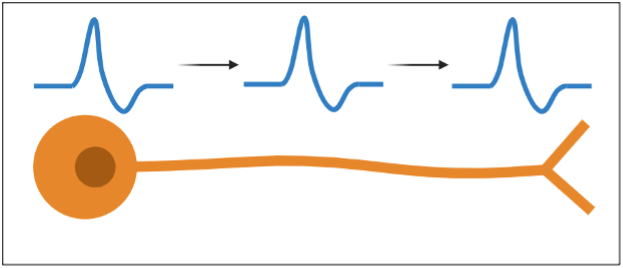

For many years now, it has been known that the brain is akin to an electrical machine. The action potential, at its core, is simply a pulse of electrical activity that flows through individual brain cells, also known as neurons. (Figure 1). But how is this pulse of electrical activity generated to begin with? As with all forms of electricity, action potentials require special charged particles known as ions. Ions can be either positively (+) or negatively (-) charged. While there are many different ions that exist in the brain, the two key ions that are essential for an action potential are sodium (Na) and potassium (K), both of which are positively (+) charged.Importantly, before an action potential starts, the amounts of sodium and potassium are quite different when looking inside versus outside of the neuron (Figure 2). Inside of the cell, a lot of potassium can be found but there is very little sodium. The opposite is true outside of the cell – a lot of sodium can be found outside of the cell but there is very little potassium. As you will soon see, it is this difference in ion balance across the cell that will allow the neuron to generate an action potential.

Mechanisms of an action potential

Before we can understand how the aforementioned ion imbalance produces an action potential, there is one more really important concept that we have to discuss. For neurons to generate electricity, ions need to flow between the inside and the outside of the neuron. As an example, think about how important it is for people to move in and out office buildings on a busy workday. In this scenario, we use doors to help us manage the flow. In a similar way, neurons have special proteins called channels that are located on the surface of the cell and can be open or closed – just like doors. When channels are open, ions are allowed to flow through them. One important difference between doors and channels is that, whereas doors allow anyone to pass through, channels only allow specific ions to travel between the inside and outside of the neuron. As you might expect, an open sodium channel will allow sodium ions to flow, and an open potassium channel will allow potassium to flow. But even if the channels are open, how do the ions know which direction to flow? Inside the cell or outside? The answer is that, under normal circumstances, ions flow toward the side that has less of that ion. If you recall from earlier, there is a lot of sodium outside of the cell and less inside of the cell. Therefore, if a sodium channel were open, sodium would flow into the cell, where there is less sodium. The opposite is true for potassium. If a potassium channel were open, potassium would flow out of the cell, since there is a lot of potassium in the cell and less potassium outside of the cell. Closing channels stops the flow of ions – just like how closing doors stops the flow people.

At this point you might be wondering: What causes these channels to be open or closed in the first place? To answer this question, lets return to our analogy of a door – except now, let’s be a little more specific and imagine that our door is an automatic sliding door. What causes these kinds of doors to open? Well, they often have some kind of sensor that detects nearby motion or pressure on the floor. In other words, the door opens when there is some external signal that the door ought to be open. We can think of the sodium and potassium channels in a neuron working in a similar way! However, the external signal for neuron is, perhaps counterintuitively, electrical activity from an outside source. Typically, the outside source is a different neuron that connects to it, but in a laboratory setting, the outside source could be an experimenter introducing electrical pulses into the cell. Now, what about when the channel closes? Let’s think back to our automatic sliding door example. These doors close when the external signal is gone (i.e., no one is moving in front of the door) and, importantly, after some amount of time has passed. In a very similar way, channels close when the outside signal (i.e., electrical signal) is gone and after some amount of time has passed.

An action potential in action

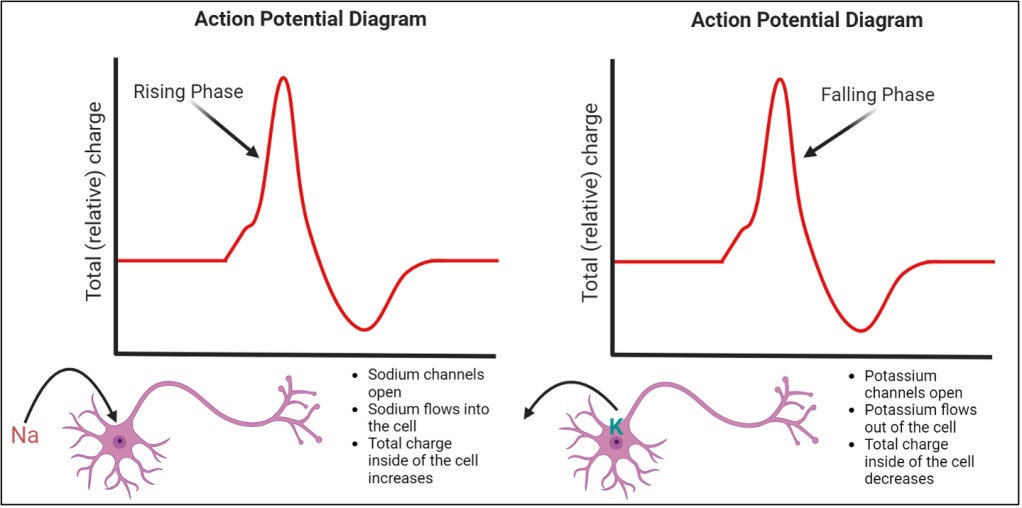

Altogether, the features that we have described now set the stage for an action potential to occur! When the neuron undergoes an action potential, sodium channels (but not potassium channels) open which allows sodium to flow into the cell. Why do sodium channels open first and not potassium? You can think of sodium channels as being a really fast and sensitive automatic sliding door and potassium channels as being a very slow and less sensitive automatic sliding door. Since sodium is a positively charged particle and sodium channels have opened, sodium flows into the cell, increasing the amount of positive charge in what is called the “rising phase” of the action potential (Figure 3, left). After some time passes, sodium channels close and potassium channels open. Potassium flows out of the cell and, since potassium is also a positively charged particle, this decreases the amount of positive charge inside of the cell and results in what is called the “falling phase” of the action potential (Figure 3, right).

What action potentials tell us

Great! Now we understand what an action potential is. But how do action potentials relate back to the idea of brain activity? Like I said at the start, many measurements of brain activity aim to capture actions potentials. More specifically, measurements of brain activity are often interested in how frequently action potentials occur, typically referred to as rate coding. A great deal of information can be communicated by rate coding. As an example, let’s say that you are trying to cross the street safely. In order to do this, it is important for you to know whether cars are moving towards you or not. We know if objects are moving because we have neurons in visual areas of the brain are sensitive to motion1. These neurons will have more action potentials when presented with a moving visual object, but no or few action potentials when presented with a static visual object2. Therefore, if a car were moving while you were trying to cross the street, the motion selective neurons would have many action potentials, and you would know that it is not safe to cross. Conversely, if there are no cars moving, the motion selective neurons would have few or no action potentials and you would know that it is safe to cross the street.

This is just one example of the kind of information that can be encoded by action potentials, but it is easy to think of real-life scenarios that are more complex and with a lot more information to consider. If we go back to the road crossing example, there may be a situation where some cars are stationary while others while others are moving. Or perhaps there are many cars moving, but their movement will not deter you from crossing and traffic officer is inviting you to cross. Because real-life scenarios are complex, we often have to weigh different pieces of information and decide what the best course of action is. These pieces of information are often represented by the rate coding of different, individual neurons in the brain. Importantly, these different neurons may be located in entirely different parts of the brain! Recognizing this, neuroscientists are now beginning to measure brain activity over multiple areas and across hundreds, if not thousands, of neurons simultaneously. This has led to the development of numerous methods of measuring brain activity including fMRI, which provides a quick and dirty glance at brain activity across all areas, and neuropixels, which allow recording of action potentials from hundreds of neurons across multiple brain areas.

Concluding Remarks

With the arrival of new and fancy tools for measuring activity across large parts of the brain, it can be easy to forget about the small-scale phenomenon that takes place in each individual neuron – the action potential. The description of the action potential that I have outlined here is simplified down to the basics as there are numerous other factors that influence action potentials. If you are interested in learning more about the fundamentals of how action potentials work, I have included some resources in the section below the reference section.

References

- Britten KH, Shadlen MN, Newsome WT, Movshon JA. Responses of neurons in macaque MT to stochastic motion signals. Vis Neurosci. 1993 Nov-Dec;10(6):1157-69. doi: 10.1017/s0952523800010269. PMID: 8257671.

- Katz LN, Yates JL, Pillow JW, Huk AC. Dissociated functional significance of decision-related activity in the primate dorsal stream. Nature. 2016 Jul 14;535(7611):285-8. doi: 10.1038/nature18617. Epub 2016 Jul 4. PMID: 27376476; PMCID: PMC4966283.

Resources

- Electrophysiology of the Neuron. Stanford University. Resource webpage: https://eotn.stanford.edu/. Textbook: https://hlab.stanford.edu/eotn/ELECTROPHYSIOLOGY%20OF%20THE%20NEURON.pdf

- Introduction to Electrophysiology. Photometrics. https://www.photometrics.com/learn/electrophysiology/introduction-to-electrophysiology

- Electrophysiology Fundamentals, Membrane Potential and Electrophysiological Techniques. Technology Networks. https://www.technologynetworks.com/neuroscience/articles/electrophysiology-fundamentals-membrane-potential-and-electrophysiological-techniques-359363#:~:text=Electrophysiology%20is%20the%20measurement%20of,hundreds%20or%20thousands%20of%20cells.

Cover Photo by Loaivat from pixabay.com

Figures 1-3 made by Jafar Bhatti.