September 24th, 2024

Written by: Kara McGaughey

With each beat of your heart, blood is pumped through an intricate highway of blood vessels that reach and nourish every tissue in your body. On average, the heart beats around 100,000 times a day, pumping enough blood to fill an 8×10 foot swimming pool!1 Given that the brain requires a tremendous amount of energy, it’s no surprise that approximately 15% of the blood pumped through the heart is dedicated to fueling and sustaining brain function.2,3 This oxygen-rich blood travels to — and throughout — the brain via a sprawling network of blood vessels. The border formed between these blood vessels and your brain tissue is called the blood-brain barrier.

In this post, we will explore why we need a blood-brain barrier, how its unique properties support healthy brain function and can relate to brain dysfunction during disease, as well as how the blood-brain barrier might hold the key to future routes for drug delivery.

Why have a blood-brain barrier?

Unlike your kidneys, which were explicitly designed to filter blood and remove waste, your brain doesn’t have a built-in filtration system. This means that, without an additional barrier around your blood vessels, anything circulating in your blood could pass freely into your brain. There are a whole host of things in your bloodstream (e.g., bacteria, viruses, potential toxins you may have been exposed to, etc.) that you wouldn’t want trickling into your brain, but the importance of the blood-brain barrier goes far beyond these top-of-mind examples.

For instance, take the neurotransmitter glutamate, a chemical messenger that is incredibly important for brain function, learning, and memory.4,5 In addition to being made in the brain, glutamate is present in many of the foods we eat, like meats and cheeses.6 If, after we ate a particularly glutamate-heavy meal, the glutamate in our bloodstream could flow freely into our brains, the effects would be catastrophic. Too much glutamate causes overactivation of neurons in the brain, which can lead to seizures and cell death.4,7 And it’s not just neurotransmitters, like glutamate, that the brain needs to keep in check. Ions, like potassium, calcium, sodium, and magnesium, are critically important for neurons to function and signal properly. The bloodstream has far higher and far less stable concentrations of these ions than the brain can support.4

In short, the brain is incredibly sensitive! It needs a highly-controlled environment in order to function properly, requiring protection from fluctuations in nutrients, hormones, ions, and other substances circulating in the blood.8 It’s the job of the blood-brain barrier to maintain these specialized conditions by tightly regulating what comes into and exits the brain in the bloodstream.

How does the blood-brain barrier work?

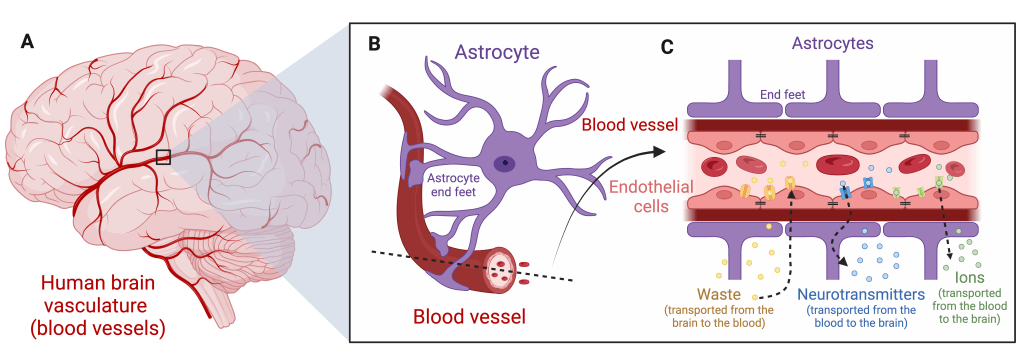

The blood-brain barrier is the intersection between blood vessels and brain tissue.4,9 It’s less of a barricade or single checkpoint in space and more of a long and winding biological (Living!) barricade between the bloodstream and the brain (Figure 1A).

The walls of blood vessels throughout the brain and the body are formed by endothelial cells.4,9 In the brain, where extra protection and filtration is needed, these endothelial cells are held together by strong connections called tight junctions (Figure 1C, black lines).9 Tight junctions seal the tiny space between endothelial cells, preventing leakage of ions and molecules from the bloodstream to the brain and vice versa. With the gaps between neighboring endothelial cells sealed, very little is slipping through the cracks. Instead, much of the transport across the blood-brain barrier happens in a highly-regulated way through transport channels. Some transport channels move waste from the brain into the bloodstream for disposal while other transport channels aid the movement of ions (sodium, potassium, calcium, etc.) or amino acids, like glutamate, from the bloodstream into the brain (Figure 1C). Blood vessels are also surrounded by a cell type called astrocytes.10 Astrocytes have long arm-like extensions that end in special structures called endfeet, which wrap around the outside of blood vessels in the brain (Figure 1B-C). These endfeet have been shown to support the blood-brain barrier by releasing chemicals that can tighten tight junctions and regulate the transport channels nestled in endothelial cells.10,11

Suffice it to say, helping the brain keep its peace and maintain a healthy, functional environment is an all-hands-on-deck operation. Endothelial cells, astrocytes, and interactions between the two are necessary to tightly regulate the exchange of materials with the bloodstream.

How is the blood-brain barrier involved in disease?

There is a growing list of brain disorders involving blood-brain barrier dysfunction, including Parkinson’s disease, Alzheimer’s disease, multiple sclerosis (MS), stroke, epilepsy, head trauma, and even chronic inflammatory pain.7,9 Here, we will unpack how different parts of the blood-brain barrier are involved in disease.

- Increased leakage across the blood-brain barrier: A recent study explored whether patients with Parkinson’s disease have a leakier blood-brain barrier by injecting a special dye into the arms of patients (and control subjects) and measuring how much crossed from their bloodstream into their brain. Researchers found more dye in the brains of Parkinson’s patients than they did in healthy individuals, suggesting that the disease may involve a leakier blood-brain barrier.12 A similar change to the integrity of the blood-brain barrier has been noted following stroke.7

- Disrupted transport channels: Another way the blood-brain barrier might contribute to disease is through disruption of transport channels. For example, channels that allow ions, like sodium and potassium, to pass can be disrupted in patients after stroke. Eventually, this disruption can change ion concentrations in the brain and negatively affect neural activity.9 Dysfunctional transport channels have also been connected to Alzheimer’s disease. Amyloid beta (the protein that accumulates into the plaques characteristic of Alzheimer’s disease pathology) is regularly transported across the blood-brain barrier through a specialized transport channel. This transport process is altered during Alzheimer’s disease, and is thought to be one reason amyloid beta plaques build up — particularly around blood vessels — in the brain.4

- Altered astrocyte function: Both multiple sclerosis (MS) and Parkinson’s disease have been associated with changes in astrocyte function.13,14 Specifically, research in mouse models suggests that as astrocytes respond to brain inflammation, their structure changes. These changes in structure can cause the astrocyte’s endfeet to lose contact with blood vessels, meaning that — without endfeet support — the blood-brain barrier is weakened.15

Can we target the blood-brain barrier for brain disease treatment?

The medications we take (either by IV injection or by mouth) have relatively easy access to the network of blood vessels throughout our body that help them make their rounds. However, because of the blood-brain barrier, these same medications are barred from entry into the brain. In fact, research shows that the blood-brain barrier blocks 95-98% of the molecules used in drug development, which is a substantial setback for brain disease treatments.16 Nevertheless, major efforts have been made to penetrate or bypass the blood-brain barrier in order to deliver drug therapies directly to the brain itself.

One creative and relatively straight-forward approach is to leverage the blood-brain barrier’s own transport system by attaching drugs to amino acids that can cross from the bloodstream into the brain through transport channels.16,17 So far, however, this line of work has had limited success.17

Another attractive technique makes use of ultrasound technology and microscopic bubbles. These so-called “microbubbles” (Think: highly-engineered bubbles 50 times smaller than the width of 1 human hair) are injected into the bloodstream and begin circulating. While the blood-brain barrier does its job, microbubbles are confined inside blood vessels. However, when an ultrasound signal is applied to the skull, the blood-brain barrier beneath is shaken open just enough for the microbubbles to squeeze their way from the bloodstream to the brain.18 For now, these microbubbles are filled with a chemical scientists can reliably locate inside the brain, but one day they could be filled with a drug of choice.18 While creating an opening in the blood-brain barrier sounds like something out of a science fiction movie, the technology is becoming increasingly reliable in animal models and is certainly something to keep an eye on in the future.

The take home? Your brain does a remarkable job of establishing and maintaining biological boundaries that protect its unique environment from disruption. We still have a lot to learn about the blood-brain barrier, but new knowledge about its function — and its dysfunction — can directly inform strategies for future brain treatments.

References

- How Blood Flows Through Your Heart & Body. (n.d.). Cleveland Clinic. Retrieved September 16, 2024, from https://my.clevelandclinic.org/health/articles/17060-how-does-the-blood-flow-through-your-heart

- Raichle, M. E., & Gusnard, D. A. (2002). Appraising the brain’s energy budget. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 99(16), 10237–10239. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.172399499

- Clarke, D. D., & Sokoloff, L. (1999). Regulation of Cerebral Metabolic Rate. In Basic Neurochemistry: Molecular, Cellular and Medical Aspects. 6th edition. Lippincott-Raven. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK28194/

- Kadry, H., Noorani, B., & Cucullo, L. (2020). A blood–brain barrier overview on structure, function, impairment, and biomarkers of integrity. Fluids and Barriers of the CNS, 17(1), 69. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12987-020-00230-3

- Gasmi, A., Nasreen, A., Menzel, A., Gasmi Benahmed, A., Pivina, L., Noor, S., Peana, M., Chirumbolo, S., & Bjørklund, G. (2022). Neurotransmitters Regulation and Food Intake: The Role of Dietary Sources in Neurotransmission. Molecules, 28(1), 210. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules28010210

- Loï, C., & Cynober, L. (2022). Glutamate: A Safe Nutrient, Not Just a Simple Additive. Annals of Nutrition & Metabolism, 78(3), 133–146. https://doi.org/10.1159/000522482

- Abbott, N. J., Patabendige, A. A. K., Dolman, D. E. M., Yusof, S. R., & Begley, D. J. (2010). Structure and function of the blood–brain barrier. Neurobiology of Disease, 37(1), 13–25. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nbd.2009.07.030

- Bernacki, J., Dobrowolska, A., Nierwińska, K., & Małecki, A. (2008). Physiology and pharmacological role of the blood-brain barrier. Pharmacological Reports: PR, 60(5), 600–622.

- Daneman, R., & Prat, A. (2015). The Blood–Brain Barrier. Cold Spring Harbor Perspectives in Biology, 7(1), a020412. https://doi.org/10.1101/cshperspect.a020412

- Abbott, N. J., Rönnbäck, L., & Hansson, E. (2006). Astrocyte–endothelial interactions at the blood–brain barrier. Nature Reviews Neuroscience, 7(1), 41–53. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrn1824

- Cabezas, R., Ávila, M., Gonzalez, J., El-Bachá, R. S., Báez, E., García-Segura, L. M., Jurado Coronel, J. C., Capani, F., Cardona-Gomez, G. P., & Barreto, G. E. (2014). Astrocytic modulation of blood brain barrier: Perspectives on Parkinson’s disease. Frontiers in Cellular Neuroscience, 8, 211. https://doi.org/10.3389/fncel.2014.00211

- Al-Bachari, S., Naish, J. H., Parker, G. J. M., Emsley, H. C. A., & Parkes, L. M. (2020). Blood–Brain Barrier Leakage Is Increased in Parkinson’s Disease. Frontiers in Physiology, 11. https://doi.org/10.3389/fphys.2020.593026

- Wosik, K., Cayrol, R., Dodelet-Devillers, A., Berthelet, F., Bernard, M., Moumdjian, R., Bouthillier, A., Reudelhuber, T. L., & Prat, A. (2007). Angiotensin II Controls Occludin Function and Is Required for Blood–Brain Barrier Maintenance: Relevance to Multiple Sclerosis. Journal of Neuroscience, 27(34), 9032–9042. https://doi.org/10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2088-07.2007

- Booth, H. D. E., Hirst, W. D., & Wade-Martins, R. (2017). The Role of Astrocyte Dysfunction in Parkinson’s Disease Pathogenesis. Trends in Neurosciences, 40(6), 358–370. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tins.2017.04.001

- Booth, H. D. E., Hirst, W. D., & Wade-Martins, R. (2017). The Role of Astrocyte Dysfunction in Parkinson’s Disease Pathogenesis. Trends in Neurosciences, 40(6), 358–370. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tins.2017.04.001

- Dong, X. (2018). Current Strategies for Brain Drug Delivery. Theranostics, 8(6), 1481–1493. https://doi.org/10.7150/thno.21254

- Puris, E., Fricker, G., & Gynther, M. (2022). Targeting Transporters for Drug Delivery to the Brain: Can We Do Better? Pharmaceutical Research, 39(7), 1415–1455. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11095-022-03241-x

- Song, K.-H., Harvey, B. K., & Borden, M. A. (2018). State-of-the-art of microbubble-assisted blood-brain barrier disruption. Theranostics, 8(16), 4393–4408. https://doi.org/10.7150/thno.26869

Cover photo by 00luvicecream from Pixabay.

Figure 1 made with BioRender.com.