August 1st, 2023

Written by: Joseph Gallegos

For a short amount of time after our evolutionary split from chimpanzees (short on the evolution timescale meaning several thousand years…), ancient humans shared the world with our cousins: the Neanderthals, and the Denisovans1. Like ancient humans, Neanderthals and Denisovans are believed to have been cognitively advanced beyond their humble beginnings of being great apes in Eastern Africa. They also walked upright, lived in tool-making groups of hunter-gatherers, and likely even made artwork and jewelry 2. But as you may have noticed, there aren’t any Denisovans or Neanderthals around today. While the reasons for the extinction of these other advanced primates are controversial, and ultimately unknowable, one hypothesis is that by the time ancient humans overlapped with our cousins we were already much more cognitively advanced3. Humans driven by a newfound ingenuity could out-compete Neanderthals and Denisovans for resources3. But given that we share approximately 99.7% of our DNA with our close cousins4,5, how could our brains have stood out so much to give us an advantage?

Dusting off ancient DNA for clues

A major challenge in understanding the brain development of ancient species is that we can only speculate, as it is very unlikely for mushy brain tissue to survive and be preserved thousands of years later. However, anthropologists and biologists can find clues based on relics leftover in the DNA collected from fossils of our now lost cousins4,5. Essentially, by comparing the DNA ‘blueprints’ that are used by humans to those that were used by our ancient cousins, we can begin to reconstruct how they built their brain differently from us.

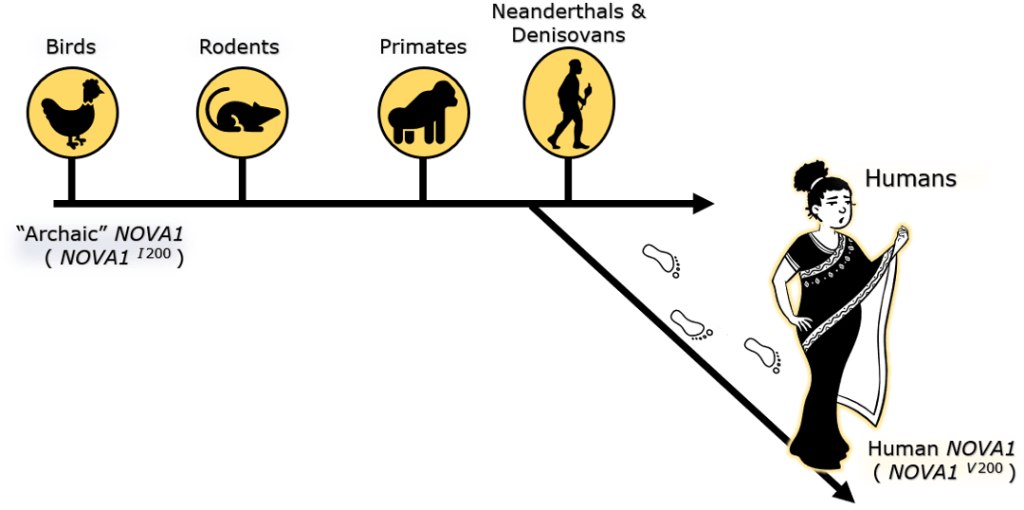

One segment of DNA that caught scientists’ attention was a gene called NOVA1. NOVA1 is a gene that is found in our ancient relatives, but intriguingly, the human version of this gene contains a mutation not found in any other species analyzed (Figure 1) 4–6 . NOVA1 has a well-documented history in the field of neuroscience, where previous studies have shown it has a critical job in keeping neurons in the brain alive7, and functioning properly8. By combing through ancient DNA, scientists now had a human-specific mutation in a key gene involved in brain development that could give us clues on how our brains were able to be sculpted a little differently. How can we study how a human-specific mutation can alter brain development? Until recently, it has been difficult to study brain cells that come from humans, because 1) collecting cells from human brains is a very, very rare opportunity, and 2) even if you could get these cells, it is practically impossible to keep them alive in a petri dish for long enough to study and manipulate them. However, the recent development of a new biological model called ‘organoids’ , allows scientists to study mini versions of brains that are made entirely from human cells! How these brain organoids are made is outside the scope of this article, but please read our previous post for more details! Organoids not only provide scientists with a model of human brain development that can fit within an ice cube tray, but these mini brains also allow them to study how changes to genes, called mutations, can influence their development. Equipped with these brain organoids, neuroscientists at the University of California, San Diego, set out to discover how converting the human NOVA1 gene back to the archaic version changes how these mini brains grow and function6.

Ancient brains in a dish

Since brain organoids are made from human cells, they already have the unique human version of NOVA1. Therefore, to study the ancient variant of this gene, the researchers used handy-dandy molecular scissors, that can snip out the human NOVA1 and replace it with the more ancient version. Then, the researchers allowed the ancient mini brains to grow side-by-side with standard human ones. One of their first observations was that organoids with the ancient NOVA1 gene tended to be smaller in size compared with human NOVA1 organoids. One of the primary roles for NOVA1 during brain development is to select, and modify the types of genes that brain cells ‘turn on’ to aid in their development. You can think of NOVA1 kind of like the person running the assembly line – they get to pick and choose which types of materials are being shipped out for the brain to use. When they compared the assembly lines of human and ancient organoids, they found that there were hundreds of different building materials that were being shipped out distinctly to each one. At a glance, it seems like the human NOVA1 keeps the brain in ‘build mode’, where the ancient NOVA1 has already closed the factory.

But do these different building styles lead to different brain cell function in these organoids? Many of the genes (building materials) that are being continuously used by human organoids are those involved in forming and maintaining synapses. Synapses are a vital part of normal brain function, as they are the interface where two brain cells communicate with one another. Sure enough, when the researchers zoomed in and looked for synapses, they saw that organoids with human NOVA1 had a greater number, and that their synapses were more fully assembled compared to ancient NOVA1 organoids. These observations suggest that NOVA1 in humans allows the brain to build functioning synapses faster and in greater number, which helps explain their bigger size too.

Overall, these findings suggest that a single mutation that arose in humans had drastic effects on the tools the brain used during development, and that the human variant of NOVA1 prompted the brain to develop more rapidly and mature faster than our ancient cousins could.

Let’s not get a big head yet…

This study produced many fascinating insights into how a single gene mutation may have altered how our brains develop differently from other species. However, there are a few caveats to this study that are worth pointing out. Growing mini brains is a very useful tool for scientists to use, but it is important to state it is just a model for how the brain may develop. The changes that were observed in these organoid systems are really just an estimation of how NOVA1 could alter the course of brain building9. Additionally, though it makes sense that a mutation in a gene such as NOVA1 with very important roles in brain development could alter the course of human cognition, it is unlikely that this single gene explains the difference between the human brain and that of our ancient cousins, or of any other species. Despite our genetic similarity, previous studies have identified dozens if not hundreds of gene mutations that distinguish humans from Neanderthals and Denisovans4,5.

The altered function of human NOVA1 illustrated in this study serves as but one piece of the puzzle to tell us why human brains became the powerhouses they are today. Future work with more refined methods and questions will surely lead to greater insight on how human brains distinguished themselves from other primates; although I’m sure our ancient cousins would be offended if we suggested this while sharing a campfire 50,000 years ago.

References

1. Wolf AB, Akey JM. Outstanding questions in the study of archaic hominin admixture. PLoS Genet. 2018;14(5):e1007349. doi:10.1371/journal.pgen.1007349

2. Sánchez-Quinto F, Lalueza-Fox C. Almost 20 years of Neanderthal palaeogenetics: adaptation, admixture, diversity, demography and extinction. Philos Trans R Soc B Biol Sci. 2015;370(1660):20130374. doi:10.1098/rstb.2013.0374

3. Gilpin W, Feldman MW, Aoki K. An ecocultural model predicts Neanderthal extinction through competition with modern humans. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2016;113(8):2134-2139. doi:10.1073/pnas.1524861113

4. Prüfer K, Racimo F, Patterson N, et al. The complete genome sequence of a Neandertal from the Altai Mountains. Nature. 2014;505(7481):43-49. doi:10.1038/nature12886

5. Meyer M, Kircher M, Gansauge MT, et al. A high-coverage genome sequence from an archaic Denisovan individual. Science. 2012;338(6104):222-226. doi:10.1126/science.1224344

6. Trujillo CA, Rice ES, Schaefer NK, et al. Reintroduction of the archaic variant of NOVA1 in cortical organoids alters neurodevelopment. Science. 2021;371(6530):eaax2537. doi:10.1126/science.aax2537

7. Jensen KB, Dredge BK, Stefani G, et al. Nova-1 Regulates Neuron-Specific Alternative Splicing and Is Essential for Neuronal Viability. Neuron. 2000;25(2):359-371. doi:10.1016/S0896-6273(00)80900-9

8. Ule J, Ule A, Spencer J, et al. Nova regulates brain-specific splicing to shape the synapse. Nat Genet. 2005;37(8):844-852. doi:10.1038/ng1610

9. Andrews MG, Kriegstein AR. Challenges of Organoid Research. Annu Rev Neurosci. 2022;45(1):23-39. doi:10.1146/annurev-neuro-111020-090812

Cover photo by MakZin from stock.adobe.com

Figure 1 was made by Joseph Gallegos using Microsoft PowerPoint, adapted from Trujillo CA. et al., Science, 2021.

Leave a comment