June 27th, 2023

Written by: Lisa Wooldridge

Everyone knows the feeling of being sick – the chills, the overpowering exhaustion, the complete loss of interest in food. Most of us also know bacterial and viral infections are the source of our woes. In your worst moments of fever, maybe you’ve wondered how something as tiny as a little “bug” could make you feel so terrible – and why it even has to! It turns out that much of what makes us feel so badly comes not from the “bug” itself, but from our body’s attempts to fight back against it. A brain region called the hypothalamus plays a critical role in that fight.

What is the hypothalamus?

The hypothalamus (Figure 1) is a collection of cell groups that sit at the base of your brain (just underneath your thalamus, as the name suggests). The hypothalamus is a versatile structure, performing many tasks that maintain our body’s homeostasis, or balance. It is our thermostat – helping us cool down when we’re hot and warm up when we’re cold. It regulates our metabolism – driving animals to hunt or burn off fat stores when we’re running low on nutrients, or rest and store fat when resources are abundant. It controls our fight-or-flight response when we’re in danger and encourages us to rest and digest when we are safe.

The hypothalamus is able to serve these diverse roles because it talks directly to the pituitary gland – the so-called “master gland” of the endocrine system (Figure 1). The “master gland” gets its name because of its ability to send long-range messages throughout the body. By doing so, the pituitary gland regulates all the organs in our body – and, with the help of the hypothalamus, keeps us operating in a healthy balance.

Many things can interrupt our homeostasis – including trauma, chronic illness, and even pregnancy (For more on how the hypothalamus regulates homeostasis during some of these events, check out the PennNeuroKnow articles at those links). Perhaps nothing is better at throwing us out of balance than sickness. How does our hypothalamus respond to illness – and how does it bring us back to homeostasis?

Kicking off the immune response

Our body’s response to infection begins long before signals have reached the hypothalamus – sometimes even days before we know we’re sick. This response starts when a pathogen – an infectious invader that can make us sick – enters our body. Bacteria and viruses, as well as worms and fungi, are examples of pathogens that cause disease in humans and other mammals. Pathogens take advantage of our cells to help themselves survive and multiply. But they often harm us in the process. Sometimes they are poisonous to us; other times they eat up the resources our cells need, causing our cells to be damaged or die.

To survive an infection, our body must recognize and respond to these dangerous invaders. This is the job of the immune system. When the first few immune cells encounter a pathogen, especially one that they haven’t seen before, they start releasing cytokines like interleukin-1 (IL-1). These cytokines are the messengers of the immune system. They race through the body via the bloodstream, summoning immune troops to push back the invading pathogen.

When they reach the central nervous system, cytokines must cross the blood-brain barrier to alert and recruit a brain response. Like the protective walls of ancient cities only had a few well-protected gates, the blood-brain barrier has only a handful of entry points, called circumventricular organs, where traffic can pass between the central nervous system and the bloodstream with relative ease (Figure 1). One of these sits at the base of the hypothalamus in a structure called the Vascular Organ of the Lamina Terminalis (VOLT for short). The VOLT is filled with receptors that detect IL-1 and other cytokines1. That, along with its proximity to our homeostat hypothalamus, means it’s positioned perfectly to sense an ongoing immune response and initiate our brain and body’s many defensive tactics. After receiving signals from the VOLT, the hypothalamus creates many of the familiar experiences of sickness.

The Hypothalamus and Fever

The hypothalamus contains our body’s thermostat. Every living thing, from bacteria to human, has a particular temperature that they thrive at, so it’s useful to have cells that can detect the body’s temperature and respond accordingly. For humans, these cells lie within the hypothalamus, where one group of cells senses warmth (warm-sensing neurons) and cools our bodies down in response; and another group of cells senses cold (cold-sensing neurons) and warms our bodies up in response2,3. The balance of the actions of our warm-sensing and cold-sensing neurons keeps us at a toasty 98.6 degrees Fahrenheit when we are healthy. (To learn more, check out the PennNeuroKnow article on our hypothalamic thermostat)

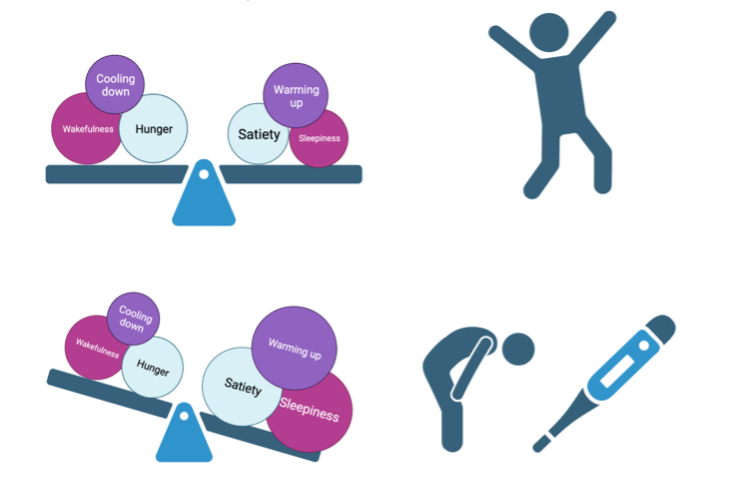

Perhaps it’s no surprise that these cells also make us feverish when we’re sick. When the hypothalamus detects cytokines it quiets the warmth-sensing neurons – shifting the balance towards the actions of cold-sensing neurons and allowing our body temperature to creep up (see Figure 2).2 The cold-sensing neurons help heat us up by sending signals to the rest of the brain that cause us to seek out warmth – like cuddling up with a partner or grabbing a blanket3. They also activate shivering reflexes by signaling to the spinal cord.4 Finally, these cold-sensing neurons send out signals to a specialized kind of tissue in our body called brown adipose tissue. Also called “brown fat”, this tissue has a unique ability to burn off sugar as heat instead of creating the energy-rich substances that are the typical product of cellular respiration.3 Even though you might not directly notice its effects, this hypothalamus-brown adipose tissue messaging is a very important part of heating you up during a fever.

Fevers aren’t just a miserable byproduct of being sick. They are an active part of our body’s fight against infection. By heating up our body, fevers bring us out of the temperature zone where bacteria and viruses can survive and thrive – which in turn helps our immune system clear out the invaders faster.

The Hypothalamus and Loss of appetite

Similar to temperature, there are two types of cells in the hypothalamus that control feeding. These cells tell other brain areas to alter our behavior – they tell us to eat more (or to stop eating), or to hunt and forage (or relax and conserve our energy instead). They also send messages, via the pituitary gland, out to the liver, the pancreas, and to adipose tissue – telling them whether to store the calories we’re taking in, or to mobilize it as fuel.5 When certain “hunger-cells” are active, we look for food, and we eat more of it. When other “satiety-cells” are active, we feel full. Ultimately, whether we feel hungry or full comes down to the balance of the activity of these neurons. When the balance is shifted towards the hunger-cells, we want to eat; when it is shifted towards the satiety-cells, we turn up our nose.

Both hunger-cells and satiety-cells are located just inside another of the circumventricular organ “gates” of the blood-brain barrier. This means they have direct access to hormones and other types of signals that are sent out from our digestive and endocrine systems when we eat. But this also means it has direct access to cytokines and other circulating immune messengers during infection. In fact, mimicking infection by injecting mice with the cytokine messenger IL-1 causes the hunger-cells to decrease their activity.6 The same cells that help drive fevers also seems to drive the activity of the hunger-off cells in the arcuate nucleus.2 Collectively, these effects tip the balance towards not wanting to eat when we’re sick (see Figure 2).

It’s unclear whether losing your appetite when you’re sick is beneficial or accidental, but it might have some advantages. When your body is otherwise preoccupied with fighting off an invading army, it has fewer resources to devote to finding food, or even to digestion. Furthermore, if by chance you caught your pathogen by eating it (like in food-borne illnesses), reducing your appetite makes it less likely that you’ll consume more of it.

The Hypothalamus and Fatigue/Sleep

Just like temperature and hunger, sleepiness and wakefulness are also driven by different groups of cells in the hypothalamus. Sleep-promoting cells initiate sleep when they are activated, while wake-promoting cells keep us alert, or even wake us up when they are active. Like other types of hypothalamic cells, the overall balance of their activity determines how sleepy or awake we feel. When sleep-promoting neurons are more active than wake-promoting neurons, we get sleepy; and when wake-promoting neurons are more active than sleep-promoting neurons, we are alert.

When those infection-triggered cytokine messengers reach the brain, they cause activity in the sleep-promoting cells of the hypothalamus.7 This increased activity shifts our balance towards sleepiness, resulting in the heavy fatigue we experience when we’re sick (see Figure 2). However, the effects of sickness on sleep isn’t straightforward. We do spend more time in non-REM sleep when we are sick.7 This is the type of sleep most associated with improving our memory, and the type you most desperately need after losing a night of sleep. In fact, cytokines also increase this type of sleep in mice.7 On the other hand, we actually spend less time in REM sleep – the stage of sleep associated with dreaming. We also often wake up during the night.

When you’re sick, the immune system’s battle with pathogens requires an incredible amount of energy, and sleeping more helps us conserve the energy we have for this fight. Even when you’re healthy, deep non-REM sleep is when your immune system kicks into its highest gear.8 It also seems to be the time where our immune system is best at learning to recognize the pathogen it is fighting off.8 This adaptive immune response is why we tend to get sick the first time we catch a particular infection, but not after that. By letting our bodies get more of this type of sleep when we’re sick, the hypothalamus is not only accelerating healing – it’s also protecting us from future infection. (For more on this topic, check out the PennNeuroKnow article on sickness-induced sleep).

The Hypothalamus is Your Body’s Healer

Though they make you miserable and throw you off-balance, these various symptoms of being sick serve a critical role – they keep the invading pathogen army at bay while your immune system beats it back. In sickness and in health, our hypothalamus works to keep us balanced (this is summarized graphically in Figure 2). And while you’re busy sweating out your fever and resting up, your immune system is hard at work figuring out how to keep the invader out next time.

References

- Ericsson A, Liu C, Hart RP, Sawchenko PE. Type 1 interleukin-1 receptor in the rat brain: distribution, regulation, and relationship to sites of IL-1-induced cellular activation. J Comp Neurol. 1995 Oct 30;361(4):681-98. doi: 10.1002/cne.903610410. PMID: 8576422.

- Osterhout JA, Kapoor V, Eichhorn SW, Vaughn E, Moore JD, Liu D, Lee D, DeNardo LA, Luo L, Zhuang X, Dulac C. A preoptic neuronal population controls fever and appetite during sickness. Nature. 2022 Jun;606(7916):937-944. doi: 10.1038/s41586-022-04793-z. Epub 2022 Jun 8. PMID: 35676482; PMCID: PMC9327738.

- Feng C, Wang Y, Zha X, Cao H, Huang S, Cao D, Zhang K, Xie T, Xu X, Liang Z, Zhang Z. Cold-sensitive ventromedial hypothalamic neurons control homeostatic thermogenesis and social interaction-associated hyperthermia. Cell Metab. 2022 Jun 7;34(6):888-901.e5. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2022.05.002. PMID: 35675799.

- https://www.physoc.org/magazine-articles/central-neural-circuitry-for-shivering/#:~:text=Shivering%20thermogenesis%20is%20driven%20by,primarily%20in%20brown%20adipose%20tissue.

- Mehay D, Silberman Y, Arnold AC. The Arcuate Nucleus of the Hypothalamus and Metabolic Regulation: An Emerging Role for Renin-Angiotensin Pathways. Int J Mol Sci. 2021 Jun 30;22(13):7050. doi: 10.3390/ijms22137050. PMID: 34208939; PMCID: PMC8268643.

- Reyes TM, Sawchenko PE. Involvement of the arcuate nucleus of the hypothalamus in interleukin-1-induced anorexia. J Neurosci. 2002 Jun 15;22(12):5091-9. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-12-05091.2002. PMID: 12077204; PMCID: PMC6757734.

- Krueger JM. The role of cytokines in sleep regulation. Curr Pharm Des. 2008;14(32):3408-16. doi: 10.2174/138161208786549281. PMID: 19075717; PMCID: PMC2692603.

- Besedovsky L, Lange T, Born J. Sleep and immune function. Pflugers Arch. 2012 Jan;463(1):121-37. doi: 10.1007/s00424-011-1044-0. Epub 2011 Nov 10. PMID: 22071480; PMCID: PMC3256323.

Cover image from Pixabay user Myriams-Fotos

Figures 1 and 2 created using BioRender.com