June 13, 2023

Written by: Andrew Nguyen

The gut microbiome is the bacterial community that exists in the gut that has become a rising star in the world of health and lifestyle trends, gaining attention as a vital player in mental health, immunity, digestion, and cognition1. Some of our past PNK posts have discussed how the gut microbiome can strongly influence many aspects of our health like how full you feel, the development of mood disorders, and even the development of the fetal brain. There is a bidirectional link between the gut and the brain called the gut-brain axis, that can change our brain activity through altering neuronal, immune, and endocrine activity. Lifestyle influencers are increasingly interested in the role of a healthy gut to improve overall health, with many companies pushing pre- and probiotic supplements, fermented diets, and other holistic dietary changes to improve gut health2. While there are many health benefits to a healthy gut, having an unhealthy gut can lead to negative repercussions. What makes an “unhealthy” gut is still widely debated amongst many scientists, but the running consensus in the field relates to having an imbalance of bad bacteria, which can lead to symptoms like bloating, weight fluctuation, sleep disturbances, metabolic dysfunctions, and inflammation3.

What’s the gut got to do with brain health anyway?

While the gut is often thought of in the context of digestion and disorders like Irritable Bowel Syndrome (IBS) and Inflammatory Bowel Disorder (IBD), the gut microbiome has recently been shown to influence the development of many neurological disorders such as Alzheimer’s Disease, Autism Spectrum Disorder, Parkinson’s Disease, Multiple Sclerosis, and even stroke4. There is a direct connection from the GI tract to the brain called the vagus nerve, which helps relay information about the inner organs to the brain.

Many scientists in the field have tools to study the microbiome’s influence on health and disease. One tool scientists use is treatment with antibiotics to get rid of the gut microbiome, creating a “germ-free animal” to look at its effects on health and physiology. Once they deplete the gut microbiome, they can re-introduce the gut microbiome by transplanting poop from a healthy animal to the germ-free animal. These tools allow scientists to make new discoveries about the microbiome and the gut-brain axis.

From the gut microbiome to exercise motivation

Some exciting research has unveiled a new role for the gut microbiome in the gut-brain axis beyond neurological diseases, finding it can influence the motivation to exercise. A recent study from the University of Pennsylvania uncovered a new role for the gut microbiome in affecting the motivation to exercise. We’ve all had the feeling of trying to go to the gym and not feeling particularly motivated to exercise. The work from this study highlights new findings that the motivation to exercise is not only encoded in the brain, but also from the gut microbiome5.

The scientists took a large cohort of mice and ranked them for how motivated they were to exercise based on exercise performance before exhaustion. They then looked at the microbial community of these highly motivated mice and found that the make-up of their microbiomes alone predicted how motivated they would be able to perform athletically. To determine that the gut microbiome really was the cause for the motivation to exercise, the scientists treated a group of mice with antibiotics to get rid of some of the bacteria in their gut and demonstrated that these mice were less motivated to exercise.

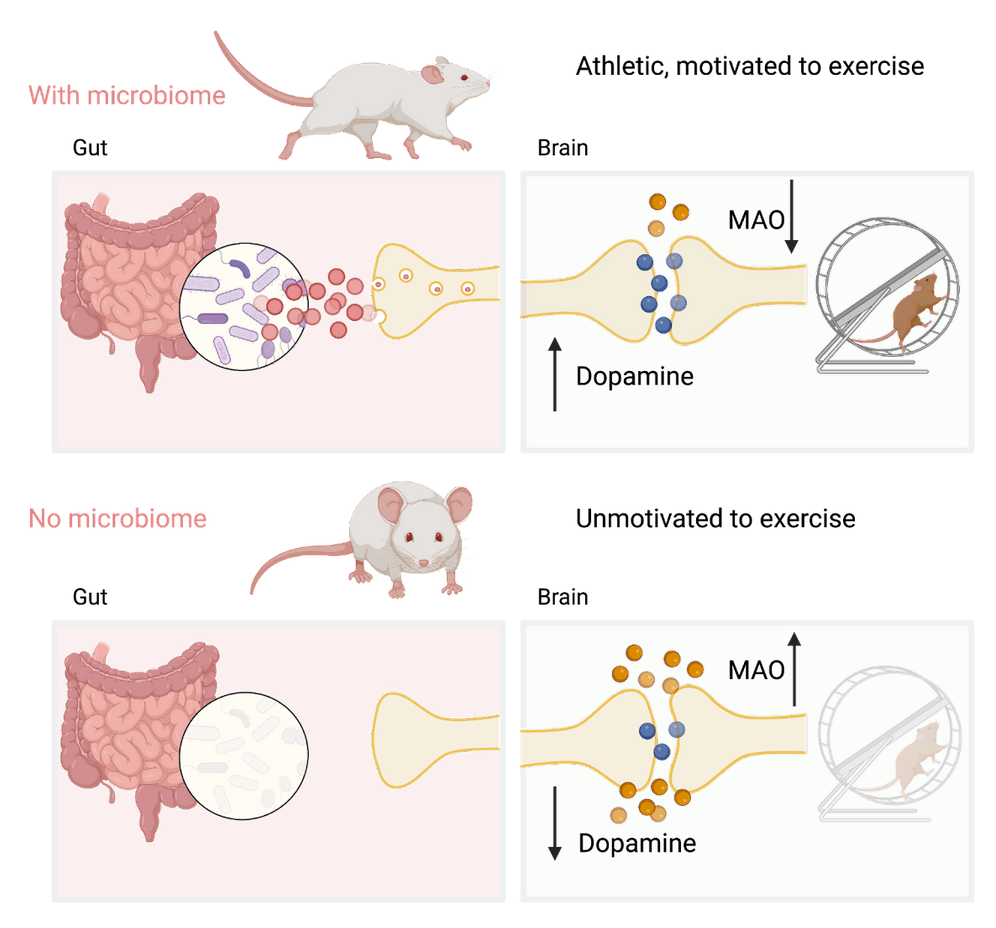

To provide additional support that the gut microbiome influences the motivation to exercise, the researchers transplanted the microbiome from healthy mice to germ-free mice and saw that they improved significantly in exercise performance. They determined that certain bacteria were producing signals that were being recognized by neurons in the gut that connect to the brain through the spinal cord. Activating these neurons leads to a decrease in an enzyme called monoamine oxidase (MAO) that degrades dopamine and other molecules. Reducing this MOA enzyme leads to an increase in dopamine activity. Exercise also releases dopamine signals from certain neurons in the brain and without a lot of MAO present to degrade it, dopamine signals are increased to promote motivation to exercise. They also showed that activating these spinal cord neurons artificially can reproduce the same improvements in exercise performance, supporting their claim that this gut-brain pathway is relevant for motivation to exercise.

The gut microbiome and the future of exercise

This incredible new finding highlighting how the gut microbiome can influence the motivation to exercise is exciting for many reasons. These results help us explain why there is so much individual variability in our motivation to exercise, despite the public knowledge of how beneficial exercise is. It also provides new insights into how we can potentially improve our motivation to exercise by shifting our diets to those that are more beneficial to the relevant bacteria in the gut. Finally, this work highlights exciting new ways that the gut microbiome influences the brain and our overall health.

References

- Ruder, Debra. “The Gut and the Brain.” Harvard Medical School, 2017, hms.harvard.edu/news-events/publications-archive/brain/gut-brain#:~:text=The%20enteric%20nervous%20system%20that,brain%20when%20something%20is%20amiss.

- Sangiuolo, Kara; Cheng, Elaine; Terala, Ananya; Dubrosa, Fiona; Milanaik, Ruth L.. The gut microbiome: an overview of current trends and risks for paediatric populations. Current Opinion in Pediatrics 34(6):p 634-642, December 2022. | DOI: 10.1097/MOP.0000000000001186

- Martinez JE, Kahana DD, Ghuman S, Wilson HP, Wilson J, Kim SCJ, Lagishetty V, Jacobs JP, Sinha-Hikim AP, Friedman TC. Unhealthy Lifestyle and Gut Dysbiosis: A Better Understanding of the Effects of Poor Diet and Nicotine on the Intestinal Microbiome. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). 2021 Jun 8;12:667066. doi: 10.3389/fendo.2021.667066. PMID: 34168615; PMCID: PMC8218903.

- Cryan JF, O’Riordan KJ, Sandhu K, Peterson V, Dinan TG. The gut microbiome in neurological disorders. Lancet Neurol. 2020 Feb;19(2):179-194. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(19)30356-4. Epub 2019 Nov 18. PMID: 31753762.

- Dohnalová, L., Lundgren, P., Carty, J.R.E. et al. A microbiome-dependent gut–brain pathway regulates motivation for exercise. Nature 612, 739–747 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-022-05525-z

Cover photo by Steven Lelham on Unsplash

Leave a comment