October 28th, 2025

Written by: Abby Lieberman

Imagine that your brain is an orchestra made up of billions of musicians. In this orchestra, each musician is a special cell called a neuron. A section of musicians, like the violins, is a brain region made up of many neurons working together to support a specific function. All of the sections come together to perform a symphony, with each part of the brain coordinated to create the thoughts and behaviors that make you who you are.

Over the past century, neuroscientists developed tools to “listen” to single neurons, or musicians in the orchestra, such as patch clamp electrophysiology. More recent techniques allow researchers to gather information from many neurons within a single brain region, which is like listening to a section of the orchestra. Over the past decade, new techniques have emerged that allow neuroscientists to monitor, or record from, thousands of neurons across multiple brain regions at once1, making it possible to hear how the neuron orchestra plays together.

Why should we record from multiple brain regions at once?

While critical discoveries have been made from recordings of single neurons and individual brain regions, these experiments tell us only what a single cell or part of the brain is doing at any given moment. But, most brain functions don’t arise from the activity of just one cell or region, but rather from coordinated patterns of brain activity that span multiple regions. In our orchestra example, this is like how listening to a solo violinist might show us what the melody of the piece is but does not let us understand what the rest of the string section is doing or how the strings fit with the other sections of the orchestra. Only when we listen to all of the instruments together can we fully appreciate the piece of music. Recording activity from groups, or populations, of neurons across multiple regions is similar in that it helps researchers understand how multiple brain regions work together at the same time. The idea that studying populations of neurons is essential for understanding what the brain is doing has become increasingly popular2 and many neuroscience labs are starting to use multiregion recording techniques that allow for simultaneous monitoring of many brain regions.

There are several ways neuroscientists can listen in on multiple brain regions at once, but most are either electrophysiological or optical techniques. Electrophysiological techniques measure the tiny electrical signals that neurons use to communicate, while optical methods use fluorescence as a measure of neural activity. Electrophysiology is extremely fast, capturing neural activity on the scale of milliseconds. In contrast, recent optical techniques capture neural activity at a slower scale, but allow researchers to record large-scale “movies” of brain activity, revealing how different cells or regions light up and interact across the brain. One particularly exciting optical technique developed over the last decade is called widefield calcium imaging, and has led to new discoveries about how many parts of the brain interact and drive behavior. Because widefield imaging involves putting special fluorescent molecules into the brain it can only be used ethically in animal subjects such as mice.

What is widefield calcium imaging?

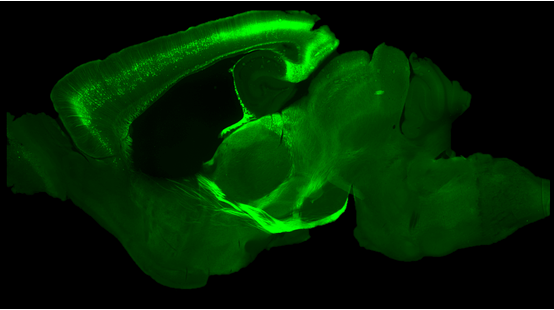

Widefield calcium imaging works by detecting changes in the amount of calcium inside neurons, which increases when a neuron is active and sending signals to other neurons. These changes are measured across a large field of view, which is where the term widefield comes from. In order to detect changes in calcium levels, researchers use a special protein called GCaMP that glows when more calcium is present in the neuron. They make sure the GCaMP protein is present inside the neurons they are interested in recording activity from by either breeding special mice that are born with GCaMP in their brains (Figure 1) or by injecting it into the brain at a later age. Researchers perform a procedure to make the mouse’s skull transparent, allowing the glow of this special protein to be recorded with a camera while the mouse either rests or engages with a task.

Because neuroscientists image through the mouse’s intact skull, widefield calcium imaging recordings capture activity across the entirety of the top-most part of the brain, called the dorsal cortex. The dorsal cortex includes brain regions that contribute to functions like moving, seeing, and sensing touch. With widefield calcium imaging we are not able to see single neurons, but rather how thousands of neurons behave together–much like listening to the entire orchestra play (Video 1)!

Looking at this video you might wonder how researchers know what part of the dorsal cortex is active at any given time. Much like how we use Google Maps to figure out where we are in the world, neuroscientists use a mouse brain atlas3 to determine which area of the brain each pixel of widefield imaging data represents. To do this, a picture of the atlas is carefully aligned to the mouse’s skull using small landmarks in the bone. Once aligned, researchers can say with confidence which parts of the dorsal cortex were active at specific times. The process of aligning the atlas is critical for linking the bright flashes of activity to what the mouse is doing at any moment. Part of what makes widefield calcium imaging especially powerful is that it can be used while mice are awake and doing a behavioral task. For example, the data in Video 1 was collected while a mouse licked at a water spout in response to an odor cue.

What have we learned from widefield calcium imaging?

For years, neuroscience research has been guided by the idea that specific parts of the brain are responsible for specific functions. For example, the motor cortex controls movement, the visual cortex processes what we see, and the auditory cortex processes what we hear. This idea came largely from studies of patients with brain lesions, where damage to one brain area caused a particular loss of function, like the inability to speak or move. This framework shaped how neuroscientists designed experiments for decades, recording from single neurons or individual brain regions (the solo violinist or the violin section) to test specific functions, often reinforcing the idea that each region has a specific function.

Studies using widefield calcium imaging are revealing a more complex picture of how the brain works. Rather than each region working in isolation, information about movement, perception, and decision making is spread across many parts of the dorsal cortex simultaneously. For example, in widefield imaging studies neural activity related to movement has been found in many areas once thought to be unrelated to movement, such as the sensory and visual cortices 4–6. Results from these studies are reshaping how neuroscientists think about the brain. Instead of viewing each region as having a single, specialized role, we now can see that information relevant to a particular function can be distributed across many regions. In other words, brain activity can be everything, everywhere, all at once. Understanding how widespread and interconnected brain activity guides behavior will ultimately help us better understand complex neuropsychiatric disorders, such as depression or schizophrenia as well, where disruptions in coordination between distributed brain regions may cause symptoms.

References

Cover photo by DeltaWorks on Pixabay

Figure 1 image taken by Abby Lieberman. Video 1 recorded by Abby Lieberman.

Leave a comment