September 2nd, 2025

Written by: Sophie Liebergall

You may have heard the common saying that people can be either “left-brained” or “right-brained.” Allegedly, people who are “left-brained” are more empathetic and creative, whereas “right-brained” people are more analytic thinkers who are drawn to numbers and logic. Despite the popularity of this theory, it is largely considered to be a myth by neuroscientists. In fact, a 2013 study1 using scans of human brain activity found no evidence that a person’s brain has a general preference for the left or right side. But perhaps this theory has remained so deeply rooted in popular culture because it is not so far from the truth: certain functions of the brain do preferentially reside on one side of the brain relative to the other.

A mirror image in form, but not in function

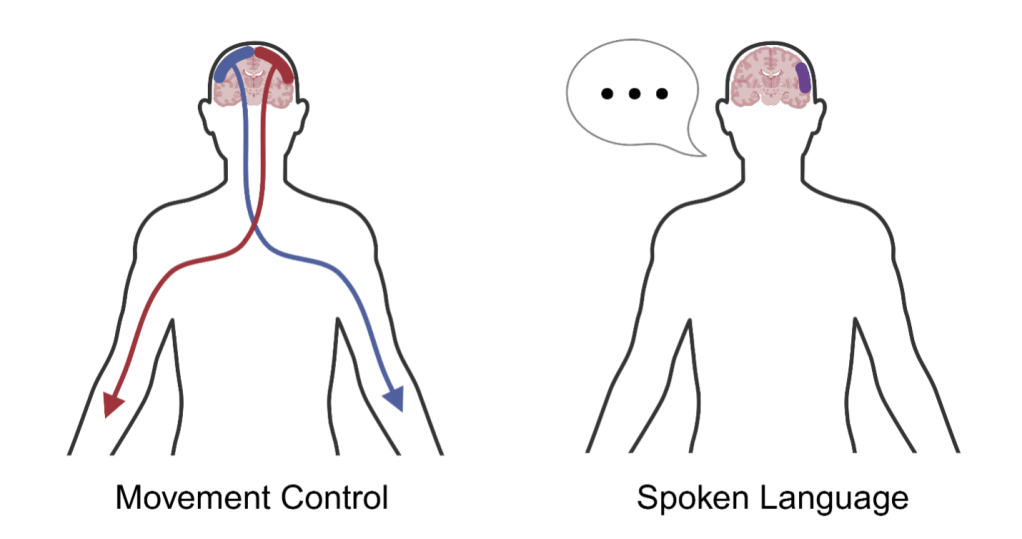

From the outside, the human brain looks symmetric in structure: the right and left sides appear to be mirror images of each other. Therefore, one might expect that the regions of the brain that execute its different functions are also symmetrically distributed across both sides. This is true for most basic functions of the brain, such as controlling your movements. There are movement control centers on both the right and left sides of the brain that are mirror images of each other (Figure 1, left). The movement control center on the right side of the brain controls the left side of the body, whereas the movement control center on the left side of the brain controls the right side of the body (which is the opposite of what you might expect). This is true for your senses as well. For example, the right side of the brain processes visual information from the left side of your field of view, whereas the left side of the brain processes visual information from the right side.

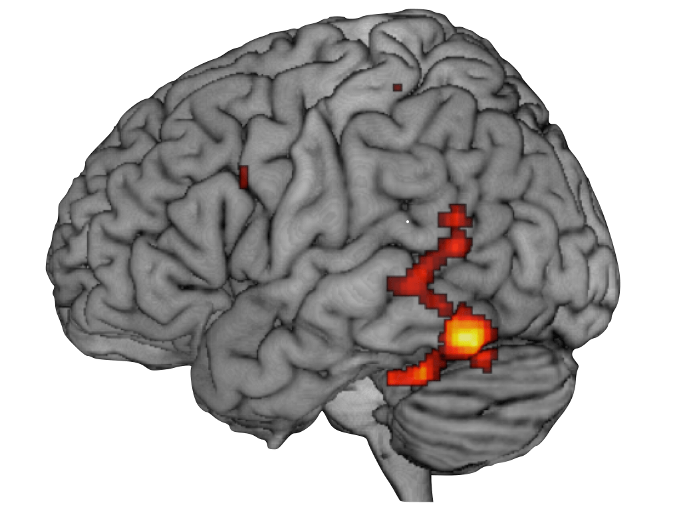

But over time, evidence has accumulated that there are some functions of the human brain that are primarily found on one side of the brain, rather than as a mirror image across both sides of the brain. In the mid-19th century, the French neurologist Paul Broca published an article reporting that twelve patients who had lost the ability to speak (but had no issues with other cognitive functions) all had damage to the same small area near the front of the brain. Surprisingly, this damaged area was on the left side of the brain in all of these patients (rather than on the left in some patients and on the right in some patients). This finding suggested that the ability to produce speech occurs in this small region that is exclusive to the left side of the brain, now referred to as “Broca’s area” (Figure 1, right).

Studies of “split-brain” patients have provided further evidence that certain human brain functions are located on only one side of the brain. “Split-brain” patients are people who have had the connections between the two sides of their brain medically severed in an attempt to treat severe seizure disorders. This means that the right side of the brain can’t access information sent to the left side of the brain, and the left side of the brain can’t access information sent to the right side of the brain. Pioneering studies in the 1960s2 tried to assess if spoken language was exclusive to one side of the brain by putting an object in a split-brain patient’s field of view such that the image would only be sent to one side of the brain or the other, then asking the patient to report if they could see it. If they showed an object to the left side of the brain, the patient could report out loud that they had seen the information. However, when they showed the object to the right side of the brain, the patient remained mute. But how did the researchers know that the right side of the brain could indeed see the object? The same patient had no trouble raising their left hand to report that they had seen the object on the right side. This suggested that in these patients, only the left side of the brain could generate spoken language.

The theory that spoken language is only generated by one side of the brain has been confirmed by multiple studies using modern techniques such as functional MRI brain scans.3 Researchers have combined different techniques to identify other functions that are only found on one side of the brain as well. In addition to spoken language, the ability to read and write language are generally found on the left side of the brain.4 For individuals who use sign language, this is generally localized to the left side of the brain as well.5 In contrast, the ability to recognize faces and attention to three-dimensional space are largely found on the right side of the brain.6,7

When the mirror is flipped

Though there are some general rules about which functions tend to be found in the right or left side of the brain, they are not set in stone. Spoken language, for example, is primarily found on the left side of the brain in 90-95% of right-handed people and only 70-85% of left-handed people.8 (In the remaining people, it is instead primarily found on the right side or more evenly spread across both sides.) Furthermore, even though spoken language is usually primarily found on the left side of the brain, if an infant has a serious brain injury that damages the spoken language area on the left side of their brain, they will generally develop the ability for spoken language on the uninjured right side of their brain instead.9 Young children, whose brains are still rapidly developing, often retain an ability to “reassign” spoken language to the other side of the brain. For instance, young children who already have spoken language primarily on the left side of their brain may be able to reassign some of their spoken language functions to the right side instead after a brain injury on the left side. But this becomes impossible during adulthood, where an injury will result in loss of spoken language without the ability to reassign the function to a new area.

How the brain assigns certain functions to one side of the brain versus the other remains a great mystery in neuroscience. We still don’t know how the brain can tell the difference between its two symmetrical sides, how it picks a side for a function, or how it knows to reassign these functions after an injury. On the other hand, asymmetries in other organs of the human body, such as the fact that the liver is found on the right side of the body, are entirely genetically determined. (The 0.01% percent of people who have their other organs flipped to the opposite side all have a known change in their genes.10)

We also don’t know why the human brain assigns certain functions to one side of the brain. Though other animals, ranging from birds to kangaroos, can show preferences for one hand over the other, the asymmetric assignment of certain brain functions seems to be a phenomenon that is exclusive to humans (and possibly some of our closest primate relatives).

Some researchers speculate that assigning complex functions like speech to one side of the brain may be a matter of efficiency. As the human brain has evolved, it has had to fit more and more functions inside the limited space of the skull. As an analogy, when you are packing the trunk of a car for a big trip, you may place the big items in the trunk first in an organized fashion. But as you pack the smaller items in later, you may just stuff them in wherever they will fit. Similarly, in early evolution, basic functions like movement control developed in an organized, symmetric fashion. Whereas later in evolution, complex functions like speech may have been added where they would fit, on only one side of the brain. Ultimately, though, this remains just a hypothesis.

Though we are still left with more questions than answers about how and why the brain assigns certain functions to only one side of the brain, further research into this phenomenon could provide insight into how the brain generally assigns and sometimes reassigns functions to different regions. This understanding could also have a major impact on the treatment of patients after major brain injuries. If we come to understand the processes through which the brain assigns a one-sided function like speech, perhaps we could try to harness the same processes to reassign functions from a region of the brain that was injured to an uninjured, healthy region of the brain. Even though a person can’t be classified as generally“left-brained” or “right-brained,” certain functions, such as their speaking voice, do indeed tend to pick sides!

References

1. Nielsen, J. A., Zielinski, B. A., Ferguson, M. A., Lainhart, J. E. & Anderson, J. S. An Evaluation of the Left-Brain vs. Right-Brain Hypothesis with Resting State Functional Connectivity Magnetic Resonance Imaging. PLOS ONE 8, e71275 (2013).

2. Volz, L. J. & Gazzaniga, M. S. Interaction in isolation: 50 years of insights from split-brain research. Brain 140, 2051–2060 (2017).

3. Rutten, G. J., van Rijen, P. C., van Veelen, C. W. & Ramsey, N. F. Language area localization with three-dimensional functional magnetic resonance imaging matches intrasulcal electrostimulation in Broca’s area. Ann Neurol 46, 405–408 (1999).

4. Baldo, J. V. et al. Voxel-based lesion analysis of brain regions underlying reading and writing. Neuropsychologia 115, 51–59 (2018).

5. Newman, A. J., Supalla, T., Fernandez, N., Newport, E. L. & Bavelier, D. Neural systems supporting linguistic structure, linguistic experience, and symbolic communication in sign language and gesture. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 112, 11684–11689 (2015).

6. Bukowski, H., Dricot, L., Hanseeuw, B. & Rossion, B. Cerebral lateralization of face-sensitive areas in left-handers: Only the FFA does not get it right. Cortex 49, 2583–2589 (2013).

7. Mengotti, P., Käsbauer, A.-S., Fink, G. R. & Vossel, S. Lateralization, functional specialization, and dysfunction of attentional networks. Cortex 132, 206–222 (2020).

8. Carey, D. P. & Johnstone, L. T. Quantifying cerebral asymmetries for language in dextrals and adextrals with random-effects meta analysis. Front. Psychol. 5, (2014).

9. Martin, K. C., Ketchabaw, W. T. & Turkeltaub, P. E. Plasticity of the language system in children and adults. Handb Clin Neurol 184, 397–414 (2022).

10. Eitler, K., Bibok, A. & Telkes, G. Situs Inversus Totalis: A Clinical Review. Int J Gen Med 15, 2437–2449 (2022).

Cover photo courtesy of Mikkelwallentin via Wikimedia commons (licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 4.0 International license).

Figure 1 made by Sophie Liebergall using BioRender.com.

Leave a comment