June 3rd, 2025

Written by: Abby Lieberman

Every day, without even thinking about it, you can instantly tell the difference between a question and a statement or between laughter and anger in someone’s voice. This skill is called auditory categorization1, and it’s a key part of how we make sense of the world. Our brains are constantly taking in a flood of sounds and quickly deciding what they mean–who’s talking, how they feel, and whether we need to react. But how exactly does the brain do this? And could it be happening in a different part of the brain than scientists previously thought?

Where sounds get their meaning

When a sound enters your ear, it sets off on a journey through many parts of the brain before arriving in the auditory cortex. Scientists have long believed that neurons in the auditory cortex give sounds their meaning and that auditory categorization happens in the cortex as well. This means that your brain waits until sound reaches the cortex to decide whether someone is laughing or angry. But, an exciting new study in big brown bats (yes, that’s really the name of the species!) is challenging this idea by showing that the brain starts sorting sounds into categories well before they reach the cortex. The results from the bat study are important because they suggest that auditory categorization may be more automatic than we thought. If categorization happens before sound reaches the cortex, it gives our brains a kind of shortcut to quickly understand what is happening around us, which is important for survival and communication.

What can we learn from Bat (Brain) Signals?

Why study auditory categorization in big brown bats? Bats are ideal for this research question because they rely heavily on sound for both social communication (like mating or competing with other bats) and navigation (using echolocation to avoid obstacles or track prey). As a consequence, bats have to consistently tell the difference between different types of calls (and do it quickly!). Also, though we seem quite different now, humans and bats actually share a common ancestor and many brain structures, including those important for auditory processing and categorization. This means that studying how bats process sound can give us clues about how our brains do too.

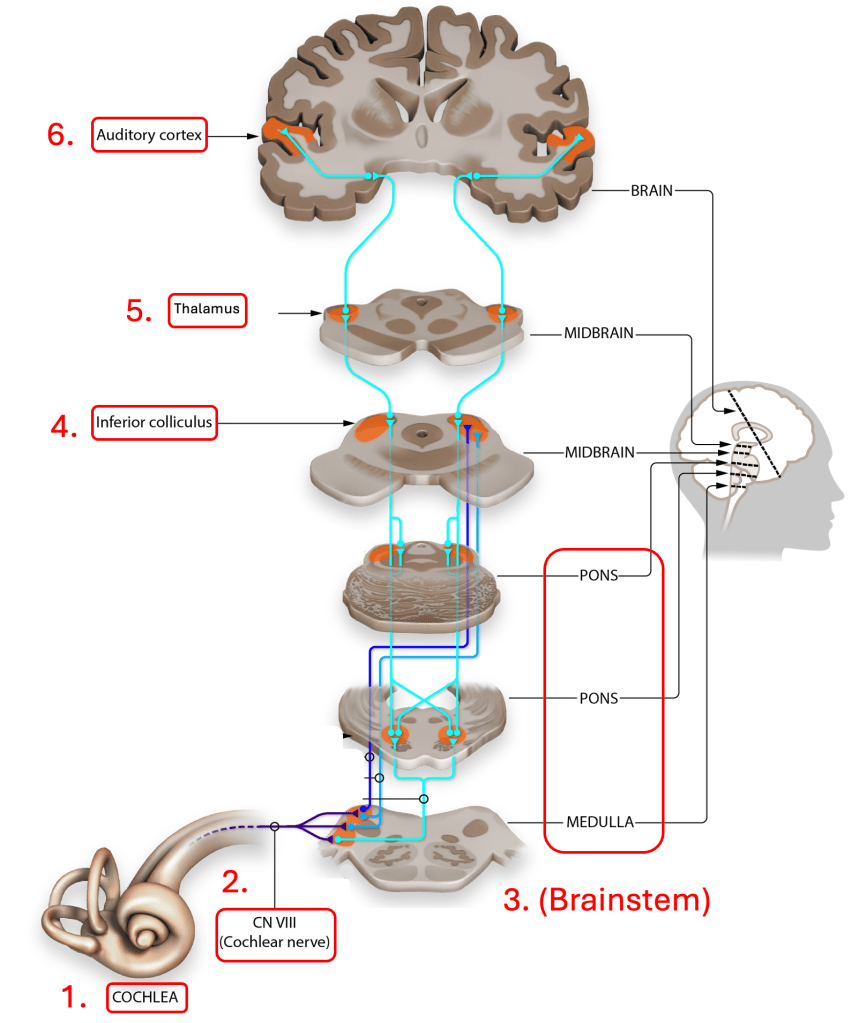

In the new big brown bat study, scientists visualized neural activity in a part of the brain called the dorsal cortex of the inferior colliculus (DCIC) while bats listened to different sounds. The researchers chose to monitor neurons in this part of the brain because of their location in the auditory pathway (Figure 1). After sound waves enter your ear, they reach the cochlea (Fig 1, Box 1), which converts sound vibrations into electrical signals. These signals travel along the cochlear nerve (Fig 1, Box 2) to the brainstem (Fig 1, Box 3), where early sound processing begins. Next, the signals move to the inferior colliculus (which contains the DCIC; Fig 1, Box 4). From there, sound information is directed through the thalamus (Fig 1, Box 5) to the auditory cortex (Fig 1, Box 6). Critically, sound information passes through the DCIC on the way to the auditory cortex.

During the experiment, bats listened to pure tones, white noise, mouse vocalizations, as well as social and navigation bat vocalizations. Most of the DCIC neurons responded more to bat vocalizations than to the other sounds. This means that these neurons help the bats process sound information that is important for communication and navigation as opposed to other common noises, including the vocalizations of other small mammals. Excitingly, some of the individual DCIC neurons visualized during the experiment were more active during social vocalizations while others were more active during navigation vocalizations. This result suggests that the DCIC is categorizing social and navigation vocalizations into two separate streams of information that can then flow to the thalamus and cortex.

After identifying neurons that prefer social or navigation vocalizations, the researchers examined where these neurons are located within the DCIC of each bat. Remarkably, they found that the neurons weren’t randomly scattered. Instead, the two kinds of neurons were grouped into their own “neighborhoods” in the DCIC. Neurons that responded to social vocalizations tended to be in the same neighborhood, while neurons that responded to navigation vocalizations were in a separate neighborhood. This pattern suggests that the bat brain may sort different types of communication signals well before the information reaches the auditory cortex.

Why do the results of this study matter?

The results from this study shift our understanding of how the brain processes sound. These discoveries suggest that the work of categorizing vocalizations, often thought to happen only once sound information reaches the cortex, starts much earlier in the brain. If the brain starts categorizing sounds in the DCIC, this could make sound processing faster and more efficient in situations where reacting quickly matters (like avoiding danger)!

While this study focused on bats, the importance of the findings extend beyond the cave. Any species that relies on complex vocal communication, including humans, could benefit from having early, efficient ways of sorting sounds. The results from this study suggest that our brains might be getting a head start on what sounds mean, long before we’re even aware of what we are hearing. So, the next time you instantly sense someone’s mood just by hearing their voice, it may be due to an efficient system deep in your brain that’s doing the hard work of categorizing sounds before you’re even aware of it. And thanks to some flying fuzzy mammals we are starting to uncover how that system really works.

References

- Tsunada, J., & Cohen, Y. E. (2014). Neural mechanisms of auditory categorization: from across brain areas to within local microcircuits. Frontiers in neuroscience, 8, 161. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnins.2014.00161

- Pickles J. O. (2015). Auditory pathways: anatomy and physiology. Handbook of clinical neurology, 129, 3–25. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-444-62630-1.00001-9

- Lawlor, J., Wohlgemuth, M. J., Moss, C. F., & Kuchibhotla, K. V. (2025). Spatially clustered neurons in the bat midbrain encode vocalization categories. Nature neuroscience, 28(5), 1038–1047. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41593-025-01932-3

- Salles, A., Loscalzo, E., Montoya, J., Mendoza, R., Boergens, K. M., & Moss, C. F. (2024). Auditory processing of communication calls in interacting bats. iScience, 27(6), 109872. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.isci.2024.109872

- Warnecke, M., Simmons, J. A., & Simmons, A. M. (2021). Population registration of echo flow in the big brown bat’s auditory midbrain. Journal of neurophysiology, 126(4), 1314–1325. https://doi.org/10.1152/jn.00013.2021

Cover photo by Rhododendrites from Wikimedia Commons.

Figure 1 by Shaishyy on Wikimedia Commons, adapted by Abby Lieberman.

Face-to-face with the earliest ancestor of all placental mammals is paywalled at the link.

What was the earliest ancestor?

“This result suggests that the DCIC is categorizing social and navigation vocalizations into two separate streams of information that can then flow to the thalamus and cortex.”

Do the separate streams also end up at different places in the auditory cortex? Do the streams also route separately to other places, such as hippocampus?

LikeLike

Hi James, thank you for your questions!

I’m so sorry about the paywall. In response to your first question: to generate a hypothetical early placental mammal, researchers combined information from fossils (ancient bones and teeth) with genetic data from living animals to build a big family tree of placental mammals. They looked at thousands of physical traits from fossils and compared those with DNA sequences to figure out when different groups, like bats and primates, first appeared and how they’re related. Based on their analysis, they believe that the common ancestor of bats and primates was probably a small, insect-eating animal that lived right after the dinosaurs went extinct. It also likely climbed trees and was nocturnal!

Here are my (non-auditory-neuroscience-expert!) thoughts on your second question:

The authors didn’t look at whether the two streams of information end up at different places in the auditory cortex or hippocampus in this study. One reason for this is that bats are an unusual model species, so the techniques that would let researchers best answer your question are not well developed in bats (compared with a more common model organism like the mouse). In fact, implementing the kind of neural monitoring they used in this study in bats is a huge feat!

However, based on what we know about the auditory system, I think it is possible that the two streams of information end up in different places in the auditory cortex. It is well established that cells in the auditory cortex exhibit what is called “tonotopy”, which means they are spaced in a way that corresponds to different pitch frequencies. To the best of my knowledge there are several studies that show specialized organization goes beyond tonotopy in the auditory cortex, and clusters of cells have been found that preferentially respond to a specific behavior. In a few different bat species it has been shown that there are neurons that respond to specific combinations of sound features. From that finding I think it’s reasonable to guess that the different calls discussed in my post, which are made of distinct sound features, could end up in different places.

The hippocampus is traditionally known for its role in memory, spatial navigation, and contextual processing and does not process raw auditory information like the regions discussed in the post. Instead, my thought is that it would integrate the information about different vocalizations with spatial and contextual information to form new memories or guide behavior. Echolocation is heavily tied to spatial processing and it is known that bats have a kind of neuron called a “place cell” that helps them understand where sounds are coming from. I found some evidence that these place cells also process social information, specifically the presence of another bat and the identity of that bat. However, it is not known whether these cells form clusters like in the DCIC.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks.

You wrote:

“The hippocampus is traditionally known for its role in memory, spatial navigation, and contextual processing and does not process raw auditory information like the regions discussed in the post.”

Isn’t the hippocampus connected to the auditory cortex? So are you just saying its auditory information is filtered through the auditory cortex?

LikeLike

BTW, this is fascinating piece while we’re on the subject of bats. Thanks again.

Forli, A., Yartsev, M.M. Hippocampal representation during collective spatial behaviour in bats. Nature 621, 796–803 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-023-06478-7

LikeLike