April 22nd, 2025

Written by: Omer Zeliger

For thousands of years, parents have been warning each other against drinking alcohol when pregnant1. This is valuable advice; consuming even small amounts of alcohol during pregnancy is associated with a wide range of symptoms for the baby – including problems with learning and memory, emotional regulation, and communication – which are collectively known as fetal alcohol spectrum disorders (FASD)2,3. How can an amount of alcohol that’s safe for the parent have such severe impacts on the child? To understand what’s going on, let’s investigate how alcohol exposure affects both adult and developing brains.

Alcohol in the adult brain

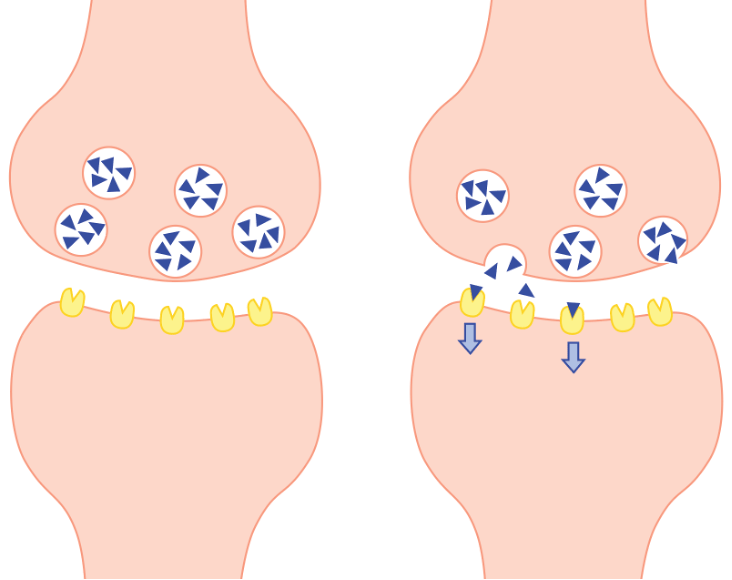

Alcohol affects our brain and changes the way we think and feel. It can make us relaxed, bold, and in extreme cases can even make us forget what happened when we were drinking. To understand how alcohol accomplishes all of this, we first need to understand how the brain works without alcohol. In the adult brain, brain cells called neurons communicate with each other through chemical signals (Figure 1). When neuron A wants to talk to neuron B, neuron A releases a chemical called a neurotransmitter. The neurotransmitter then attaches to specialized molecules, called receptors, on the surface of neuron B. Once neuron B’s receptors detect neurotransmitter, neuron B knows that neuron A has just sent off a signal. Neuron B can then decide whether to pass along the message to neuron C – if so, all neuron B has to do is release neurotransmitters of its own, which will attach to neuron C’s receptors. This process repeats until the message reaches its final destination. The brain has many, many types of neurotransmitters, each of which sends different types of messages. For example, the neurotransmitter glutamate is involved in learning and memory, and dopamine is important for reward and addiction.

How do drugs disrupt this process? Many mind-altering drugs work by mimicking the brain’s neurotransmitters and attaching themselves to specific types of receptors, hijacking the brain’s normal communication system to make it think there’s a signal when there’s really none. For example, opioids like heroin and morphine attach to and activate opioid receptors4, activating pathways associated with pain relief and addiction5. Similarly, marijuana attaches to cannabinoid receptors6, which regulate both anxiety and hunger7. Some drugs do the opposite; instead of activating the receptors, they prevent receptors from passing along the signal, even when their neurotransmitter is there. Narcan, for example, prevents heroin overdose by attaching to opioid receptors and blocking them from passing along the signal8.

What about alcohol? Alcohol works on two different receptor types: it blocks NMDA receptors and activates GABAA receptors9,10. By blocking NMDA receptors, which are critical for learning and memory11, alcohol can cause someone to forget what they were doing on a night that they got “blackout drunk”12. Alcohol simultaneously activates GABAA, a type of receptor involved in sleep and anesthesia, explaining why drinking alcohol can make people feel sleepy13. Since alcohol works by directly affecting receptors, its effects tend to be short-lived. As soon as your body finishes breaking down the alcohol molecules, they can’t attach to receptors anymore, and you no longer feel drunk. Though alcohol can have long-term effects on the brain such as memory problems and addiction, these tend to be the result of long-term drinking rather than lingering effects of one exposure14. But if alcohol’s most obvious effects on adults are short-term, how can it have such profound long-term effects on developing fetuses?

Alcohol in the developing brain

We’ve covered how chemical signals in the adult brain let neurons communicate with each other, forming thoughts and emotions and memories. In the developing brain, chemical signals are crucial for another very important job: telling the brain how to grow properly. Neurons use chemical signals to determine what type of neuron to become, what other neurons they communicate with, and even whether to survive to adulthood15. Chemical signals during development act like an IKEA instruction manual, and disrupting these signals is like tearing out the manual’s pages. If it gets wrong instructions on how to build itself during development, the brain can make assembly mistakes that stay with it for the rest of its life15,16.

In developing fetuses, NMDA and GABAA receptors both play important roles in guiding brain growth. Neurons listen to signals from both of these receptors for instructions on how to grow, so disrupting either can have permanent effects on the adult brain16-20. For example, blocking NMDA receptors20 or activating GABAA receptors18 in fetal rats, like alcohol does, causes widespread death of neurons. This means that even exposure to small amounts of alcohol during brain development can cause long-lasting changes. Even though alcohol can only directly affect the receptors while it is in the body, the assembly decisions the neurons made while under the influence will stay with them them long after the alcohol has already been cleared away.

What does this mean for daily life?

It is estimated that between 1 and 5% of first graders in the United States have FASD2, with approximately one in ten of them having an especially severe form called fetal alcohol syndrome (FAS)21. People with FASD may face lifelong challenges or need specialized intervention2,22. There is no cure for FASD, and the best protection is to avoid alcohol when pregnant or when trying to get pregnant22. With that said, it’s not always possible to avoid drinking when pregnant. Currently, the most effective treatments are childhood interventions to address specific difficulties, including speech therapy to address language delays and occupational therapy to help with motor issues22,23, though scientists are always looking into new treatments. Recent research is investigating the potential for nutrient supplements during pregnancy to minimize the negative effects of fetal alcohol exposure24. Continuing research into effective interventions is vital in order to provide effective care that gives people with FASD the best possible help.

References

- Brown, J. M., Bland, R., Jonsson, E., & Greenshaw, A. J. (2019). A Brief History of Awareness of the Link Between Alcohol and Fetal Alcohol Spectrum Disorder. Canadian journal of psychiatry. Revue canadienne de psychiatrie, 64(3), 164–168. https://doi.org/10.1177/0706743718777403

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. (2023). Understanding fetal alcohol spectrum disorders. National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism. https://www.niaaa.nih.gov/publications/brochures-and-fact-sheets/understanding-fetal-alcohol-spectrum-disorders

- Kesmodel, U. S., Nygaard, S. S., Mortensen, E. L., Bertrand, J., Denny, C. H., Glidewell, A., & Astley Hemingway, S. (2019). Are Low-to-Moderate Average Alcohol Consumption and Isolated Episodes of Binge Drinking in Early Pregnancy Associated with Facial Features Related to Fetal Alcohol Syndrome in 5-Year-Old Children? Alcoholism, clinical and experimental research, 43(6), 1199–1212. https://doi.org/10.1111/acer.14047

- Dhaliwal, A., & Gupta, M. (2023). Physiology, Opioid Receptor. In StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing.

- Valentino, R. J., & Volkow, N. D. (2018). Untangling the complexity of opioid receptor function. Neuropsychopharmacology : official publication of the American College of Neuropsychopharmacology, 43(13), 2514–2520. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41386-018-0225-3

- Zou, S., & Kumar, U. (2018). Cannabinoid Receptors and the Endocannabinoid System: Signaling and Function in the Central Nervous System. International journal of molecular sciences, 19(3), 833. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms19030833

- Mackie K. (2006). Cannabinoid receptors as therapeutic targets. Annual review of pharmacology and toxicology, 46, 101–122. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.pharmtox.46.120604.141254

- Martin W. R. (1976). Naloxone. Annals of internal medicine, 85(6), 765–768. https://doi.org/10.7326/0003-4819-85-6-765

- Tabakoff, B., & Hoffman, P. L. (1996). Alcohol addiction: an enigma among us. Neuron, 16(5), 909–912. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80113-0

- Davies M. (2003). The role of GABAA receptors in mediating the effects of alcohol in the central nervous system. Journal of psychiatry & neuroscience: JPN, 28(4), 263–274.

- Li, F., & Tsien, J. Z. (2009). Memory and the NMDA receptors. The New England journal of medicine, 361(3), 302–303. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMcibr0902052

- Nelson, E. C., Heath, A. C., Bucholz, K. K., Madden, P. A., Fu, Q., Knopik, V., Lynskey, M. T., Lynskey, M. T., Whitfield, J. B., Statham, D. J., & Martin, N. G. (2004). Genetic epidemiology of alcohol-induced blackouts. Archives of general psychiatry, 61(3), 257–263. https://doi.org/10.1001/archpsyc.61.3.257

- Nelson, L. E., Guo, T. Z., Lu, J., Saper, C. B., Franks, N. P., & Maze, M. (2002). The sedative component of anesthesia is mediated by GABA(A) receptors in an endogenous sleep pathway. Nature neuroscience, 5(10), 979–984. https://doi.org/10.1038/nn913

- NHS. (2022). Alcohol misuse. NHS choices. https://www.nhs.uk/conditions/alcohol-misuse/risks/

- Bear, M., Connors, B., & Paradiso, M. A. (2020). Neuroscience: Exploring the brain, enhanced edition: Exploring the brain. Jones & Bartlett Learning.

- Boschen, K. E., & Klintsova, A. Y. (2017). Neurotrophins in the brain: interaction with alcohol exposure during development. Vitamins and hormones, 104, 197-242.

- Naassila, M., & Pierrefiche, O. (2019). GluN2B Subunit of the NMDA Receptor: The Keystone of the Effects of Alcohol During Neurodevelopment. Neurochemical research, 44(1), 78–88. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11064-017-2462-y

- Dikranian, K., Ishimaru, M. J., Tenkova, T., Labruyere, J., Qin, Y. Q., Ikonomidou, C., & Olney, J. W. (2001). Apoptosis in the in vivo mammalian forebrain. Neurobiology of disease, 8(3), 359–379. https://doi.org/10.1006/nbdi.2001.0411

- Henschel, O., Gipson, K. E., & Bordey, A. (2008). GABAA receptors, anesthetics and anticonvulsants in brain development. CNS & neurological disorders drug targets, 7(2), 211–224. https://doi.org/10.2174/187152708784083812

- Ikonomidou, C., Bosch, F., Miksa, M., Bittigau, P., Vöckler, J., Dikranian, K., Tenkova, T. I., Stefovska, V., Turski, L., & Olney, J. W. (1999). Blockade of NMDA receptors and apoptotic neurodegeneration in the developing brain. Science (New York, N.Y.), 283(5398), 70–74. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.283.5398.70

- Popova, S., Lange, S., Probst, C., Gmel, G., & Rehm, J. (2017). Estimation of national, regional, and global prevalence of alcohol use during pregnancy and fetal alcohol syndrome: a systematic review and meta-analysis. The Lancet. Global health, 5(3), e290–e299. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2214-109X(17)30021-9

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2024). Treatment of fasds. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. https://www.cdc.gov/fasd/treatment/index.html

- Wilhoit, L. F., Scott, D. A., & Simecka, B. A. (2017). Fetal Alcohol Spectrum Disorders: Characteristics, Complications, and Treatment. Community mental health journal, 53(6), 711–718. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10597-017-0104-0

- Ernst, A. M., Gimbel, B. A., de Water, E., Eckerle, J. K., Radke, J. P., Georgieff, M. K., & Wozniak, J. R. (2022). Prenatal and Postnatal Choline Supplementation in Fetal Alcohol Spectrum Disorder. Nutrients, 14(3), 688. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu14030688

Header image by congerdesign on Pixabay

Figure 1 made by Omer Zeliger in Adobe Illustrator

Leave a comment