March 18th, 2025

Written by: Kara McGaughey

Whether it’s establishing a workout routine, decreasing screen time, or sticking to a budget, we’ve all set goals to change our behavior. If 2025 was your year of digital detox, perhaps you banned the phone from your bedroom and decided to wind down by reading a book instead. Even while doing the “right” thing, with each flip of the page you might have wished you were swiping or tapping instead. Likely, you got by for a while. But — after a series of particularly stressful days — maybe phoneless bedtime begun to slip away. Instead, maybe you found yourself re-downloading Instagram or TikTok and leaning back into the mindless, bedtime scroll. Why do we feel this constant tugging between goals and habits? And why does stress seem to push towards old habits and routines?

A tale of two pathways

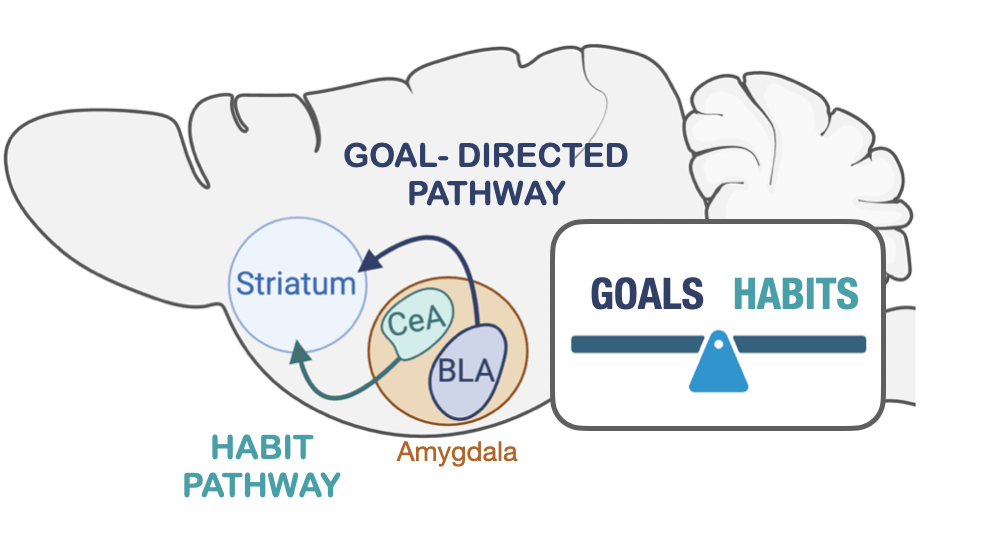

The ability to make decisions and adjust our behavior involves many brain regions. However, in a study published last month, scientists at Temple University in Philadelphia proposed that two brain pathways are particularly important for balancing what’s best (i.e., goals) and what’s easiest (i.e., habits).1 Both pathways begin in one brain region called the amygdala and end in another brain region called the striatum. Similar to how you might give directions based on where to enter and exit a highway, neural pathways are named by where they begin and end. So, these two neural highways from the amygdala to the striatum are called amygdala-striatum pathways. One amygdala-striatum pathway, which extends from the basolateral amygdala (BLA) to the striatum, is thought to support goal-directed behavior while the other pathway, which travels from the central amygdala (CeA) to the striatum, is thought to support habits (Figure 1). Because behavior is always happening, we can think of these two amygdala-striatum pathways as always being “on.” As such, the striatum is constantly “weighing” activity from each pathway and selecting actions accordingly.2 If there’s more activity coming along the BLA-striatum neural pathway, goal-directed actions, like choosing to keep your phone out of the bedroom, win out. More activity in the CeA-striatum pathway? You’ll probably find yourself back in the habit of scrolling before bed. During everyday life, the behavioral balance scale tips to and fro, allowing for a flexible range of actions that span the spectrum between goal-directed and habitual.

Stress disrupts the behavioral balancing act

Interested in understanding the ways in which stress affects this balance between goals and habits, the researchers turned to mice. To mimic the varied nature of stress, mice were subjected to a wide range of unpleasantries, including disruptions to their sleep schedule and changes to their environment, like wet bedding or constant exposure to white noise. Scientists wanted to ask how well the stressed mice could engage in flexible, goal-directed decision making compared to a group of unstressed mice and how exactly the amygdala-striatum pathways contributed to any differences they found.

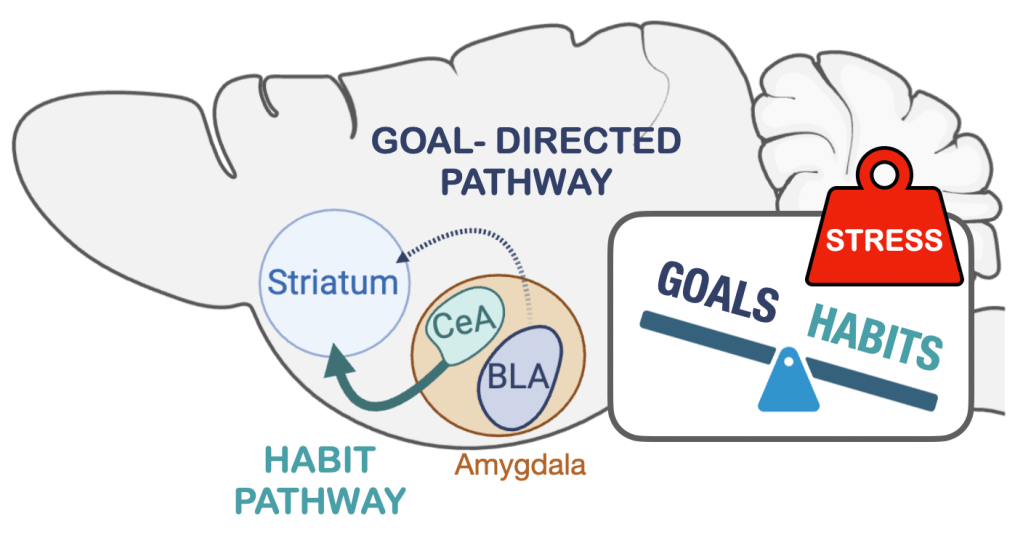

Before mice could be expected to change their behavior in a goal-directed manner (like you and your phone use during a digital detox), they had to learn a behavior. To facilitate learning, scientists removed food from the mice’s cages to ensure they were hungry. The hungry animals were then given the opportunity to earn a tasty food reward in exchange for pressing a lever with their paws. With a few days of practice, all the mice — stressed and not-stressed — learned that pressing the lever would deliver a snack. And, driven to satisfy their hunger, they exploited this behavior, pressing the lever over and over. While the mice were learning the lever-pressing behavior, researchers recorded brain activity within the amygdala-striatum pathways. They found that when the unstressed mice pressed the lever and received a snack, there were large increases in activity along the BLA-striatum goal-directed pathway. However, for stressed mice, activity increased not in their goal-directed BLA-striatum pathway, but in the habit-forming CeA-striatum pathway (Figure 2). In other words, while both groups of mice — stressed and not-stressed — were able to learn the lever-pressing behavior, there were big differences in what was happening in their brains as they learned. Stress seemed to have disrupted the balance of activity between the amygdala-striatum pathways by overweighting habits.

Now, the scientists were curious. Both stressed and not-stressed mice had successfully learned the lever-pressing behavior. However, their brains seem to have engaged the amygdala-striatum pathways in different ways with stressed animals relying more on the habit-forming pathway and less on the goal-directed pathway than not-stressed animals (Figure 2). Would this affect the ability of stressed mice to apply and adjust their behavior in a goal-directed manner? In other words, if the goal changed, could the stressed mice change their behavior accordingly?

In order to change the animal’s goals, the researchers provided mice with heaping helpings of the special treats before presenting them with the lever again. Having already filled up on snacks, if the mice were making thoughtful decisions in line with their goals, they wouldn’t bother pressing the lever. They weren’t hungry anymore, so they had no reason to perform a behavior that would earn them food. While unstressed animals successfully changed their behavior and avoided the lever altogether, stressed animals continued to press it many times per minute. There was the answer! Stress had shifted the habit-forming pathway into overdrive, disrupting the delicate behavioral balancing act and preventing the mice from flexibly adjusting their behavior to meet their goals. They were, like many of us have been, stuck on “autopilot” mode and thoughtlessly performing the same behavior over and over.

Can balance be restored?

The fact that stress disrupts the brain’s ability to balance goal-directed and habitual behavior pushes us to ask the question: Can it be fixed? In other words, if we strengthened the goal-directed pathway or weakened the habit-forming pathway, could we push the mice away from their habit and back towards something more balanced? Researchers were able to attempt both pathway rebalancing approaches using a technique that allows particular neurons in the brain to be turned on or off using light, called optogenetics. Optogenetics lets researchers control neurons and observe how it changes behavior.

First, researchers attempted to rescue goal-directed behavior in stressed animals by strengthening the goal-directed pathway (Figure 2). While the mice learned to press the lever for a food reward, the team used optogenetics to turn on BLA neurons and increase neural activity within the BLA-striatum pathway. This time, when the stressed animals were presented with the lever (now with full bellies), they successfully refrained from pressing. The external boost to their goal-directed pathway helped to counteract the effects of stress, preventing the stressed mice from falling into “autopilot” lever-smashing mode. The same was true if researchers used optogenetics to weaken the CeA-striatum habit pathway (Figure 2). By preventing CeA neurons from activating, they were again able to rescue stressed mice from falling into habit. In other words, just by manipulating the neural pathways, researchers could make the stressed mice behave just like unstressed mice — as if nothing stressful had happened.

While these experiments prove that it’s possible to overcome the effects of stress on behavior by manipulating activity of the amygdala-striatum pathways, it’s unlikely that this kind of strategy could be a long-term solution. Constantly activating one pathway or suppressing the other will, eventually, lead to an overcorrection. The behavioral balance scale will reach full tilt, unbalanced again, but now in the opposite direction. Just like how “autopilot” habit mode is detrimental to flexible, goal-directed behavior, being stuck in “goal-overdrive mode” also has downsides. Habitual, thoughtless, and routine behaviors are necessary, too. Mice (and humans) need them to maintain fast, efficient behavior. Behavior can’t be deliberate all the time. The name of the game is balance.

What does all this mean?

While this research was done using mice, there are still implications for you and me. For starters, even though humans and their brains cannot be examined and manipulated as thoroughly as is possible in mice, experiments with less-invasive measurements of brain activity suggest that we also have amygdala-striatum pathways and that these neural pathways also seem responsive to habits, goals, and rewards.3-4

Not only do the amygdala-striatum pathways appear to function similarly in humans, but there are numerous disorders in which we could explore their dysfunction. There are a whole host of disorders involving some sort of disruption to the balance between goal-directed and habitual behavior.1 For instance, the inability to suppress compulsive and repetitive behaviors is a hallmark of obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD).5 The same can be said of obesity, depression, anxiety, and autism.6-7 Additionally, for many of these conditions, there is compelling evidence that stress plays a role. That is to say, research exploring the balance — and stress-induced imbalance — of amygdala-striatum pathways, will have implications for both human health and mental illness.

So, the next time you catch yourself falling back into old habits and routines, remember that behavior is a delicate balance and your willpower is not the only thing capable of tipping the scale. Mitigating stress might be just as important for reaching your goals.

Want to learn more? Check out our recent posts on digital habits, the impact of social media on spending behavior, and the neuroscience of habit formation.

References

- Giovanniello, J. R., Paredes, N., Wiener, A., Ramírez-Armenta, K., Oragwam, C., Uwadia, H. O., Yu, A. L., Lim, K., Pimenta, J. S., Vilchez, G. E., Nnamdi, G., Wang, A., Sehgal, M., Reis, F. M., Sias, A. C., Silva, A. J., Adhikari, A., Malvaez, M., & Wassum, K. M. (2025). A dual-pathway architecture for stress to disrupt agency and promote habit. Nature. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-024-08580-w

- Cox, J., & Witten, I. B. (2019). Striatal circuits for reward learning and decision-making. Nature Reviews Neuroscience, 20(8), 482–494. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41583-019-0189-2

- Vogel, S., Klumpers, F., Krugers, H. J., Fang, Z., Oplaat, K. T., Oitzl, M. S., Joëls, M., & Fernández, G. (2015). Blocking the Mineralocorticoid Receptor in Humans Prevents the Stress-Induced Enhancement of Centromedial Amygdala Connectivity with the Dorsal Striatum. Neuropsychopharmacology, 40(4), 947–956. https://doi.org/10.1038/npp.2014.271

- O’Doherty, J. P. (2004). Reward representations and reward-related learning in the human brain: Insights from neuroimaging. Current Opinion in Neurobiology, 14(6), 769–776. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conb.2004.10.016

- Gillan, C. M., Papmeyer, M., Morein-Zamir, S., Sahakian, B. J., Fineberg, N. A., Robbins, T. W., & De Wit, S. (2011). Disruption in the Balance Between Goal-Directed Behavior and Habit Learning in Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder. American Journal of Psychiatry, 168(7), 718–726. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ajp.2011.10071062

- Horstmann, A., Dietrich, A., Mathar, D., Pössel, M., Villringer, A., & Neumann, J. (2015). Slave to habit? Obesity is associated with decreased behavioural sensitivity to reward devaluation. Appetite, 87, 175–183. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.appet.2014.12.212

- Griffiths, K. R., Morris, R. W., & Balleine, B. W. (2014). Translational studies of goal-directed action as a framework for classifying deficits across psychiatric disorders. Frontiers in Systems Neuroscience, 8. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnsys.2014.00101

Cover photo made by Kara McGaughey in PowerPoint

Figures 1 and 2 made by Kara McGaughey in PowerPoint using BioRender images.

commendable! World’s Largest Wildlife Crossing Completed 2025 supreme

LikeLike