March 11th, 2025

Written by: Catrina Hacker

Late last year, as I read through an issue of Scientific American, I encountered a piece about how dinosaurs perceived the world that blew my mind1. As a neuroscientist, I spend all my time thinking about the living brain, but I knew that paleontologists didn’t have access to living dinosaur brains. So how could we know how dinosaur brains worked without access to a living, functioning one? As I read more and learned about the fascinating field of paleoneurology (paleo– geologically old, neurology-brains), I began to wonder why I wasn’t studying dinosaur brains and knew that I wanted to learn more. Read on to hear more about what I’ve learned about the jura-sick world of dinosaur brains.

How do we study dinosaur brains?

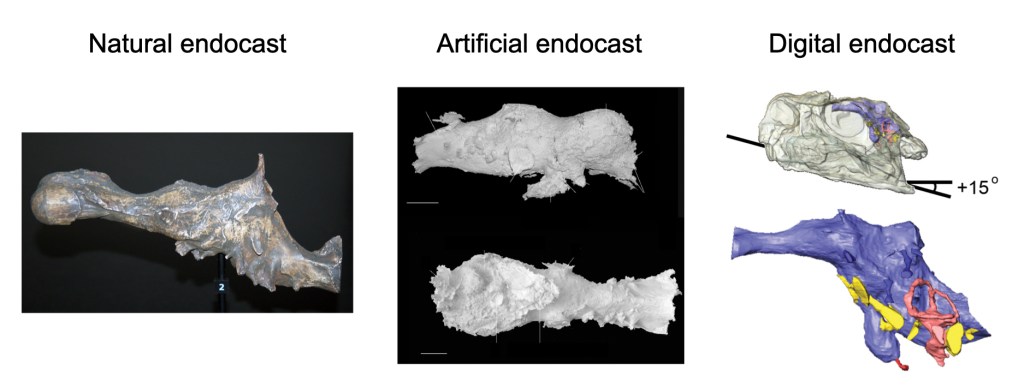

Since there aren’t any living dinosaurs running around (RIP Jurassic Park) we can’t use the same methods to study dinosaur brains that we do in the rest of neuroscience. Instead, paleoneurologists rely on molds and images of the inside of a dinosaur skull, called endocasts (Figure 1), to get an idea of the brain’s relative shape and size2. Sometimes, endocasts are formed naturally when exactly the right conditions cause a dinosaur’s skull to fill with materials that fossilize and preserve its shape2 (Figure 1, left). Such natural endocasts are rare, so early paleoneurologists also developed methods to make their own by filling dinosaur skulls with materials, like rubber or silicon, that conform to the shape of the skull before hardening3 (Figure 1, middle). However, this method risks damaging already precious specimens, often requiring the skull to be intentionally broken, and only certain skulls can be used2. Today, endocasts are made using the same scan doctors use to visualize the inside of patient’s bodies, a method called a computed tomography (or CT) scan2 (Figure 3, right). These digital scans don’t harm precious fossil skulls and allow paleoneurologists to quickly and easily create and share many more endocasts.

Once they have an endocast, paleoneurologists use what they know about the evolutionary lineage of each dinosaur, as well as their living ancestors, to make educated guesses about the dinosaur’s brain. We’ll dive into a few examples below of exactly what paleoneurologists have been able to learn using these methods.

Early approaches: brain size

One of the earliest and easiest features of endocasts to be studied was their size. One popular approach is to look at the relationship between body size and brain size for different groups of living animals and compare that to dinosaurs4. Once that relationship is determined, observing where dinosaurs fall relative to modern animals can provide some insight. For example, early studies suggested that dinosaurs had brains about as large as living reptiles given their body size and were therefore just as evolved4. Other features of endocasts, like small markings on the inside of the skull, can give more precise hints about the shape and size of different parts of the brain5.

However, there are several factors that complicate estimating brain size from an endocast and limit what we can learn from this approach. First, the brain doesn’t fill the entire skull cavity in all species. In mammals and birds, the brain fills the skull cavity, while in other vertebrates it doesn’t6. Early studies assumed that dinosaurs were reptile-like and measured their brains at about half the size of an endocast4. However, we can’t know for sure how much of the endocast was filled by the brain, and scientists continue to use new insights to improve their estimates for various kinds of dinosaurs7.

Further, paleoneurologists continue to debate exactly how accurately the small markings of the skull indicate the precise shape of the brain. One recent study made digital endocasts of living human brains alongside high-resolution images of the brain itself. The researchers then asked experts to label the folds of the human brain based on the digital endocasts (as though they were paleoneurologists trying to do the same for a dinosaur). They then compared their estimates to the brain images that showed where the folds really were. Experts did a reasonably good job of identifying where the brain was folded based on the endocast alone, meaning this method could be very accurate. However, it is still impossible to know just how accurate it is for dinosaur brains in the absence of a real one to compare the estimates with5.

Beyond brain size

Ultimately, even if endocasts were a perfect reflection of brain size, the kinds of conclusions that can be made based on brain size alone are limited. Brain size is not a perfect predictor of intelligence and doesn’t distinguish specific abilities. More meaningful conclusions about dinosaurs’ abilities require more specific observations. Many of the strongest conclusions made by paleoneurologists rely on observations about specialized brain regions with known functions and relationships to size in living animals. We’ll look at three specific examples below.

Olfactory bulb

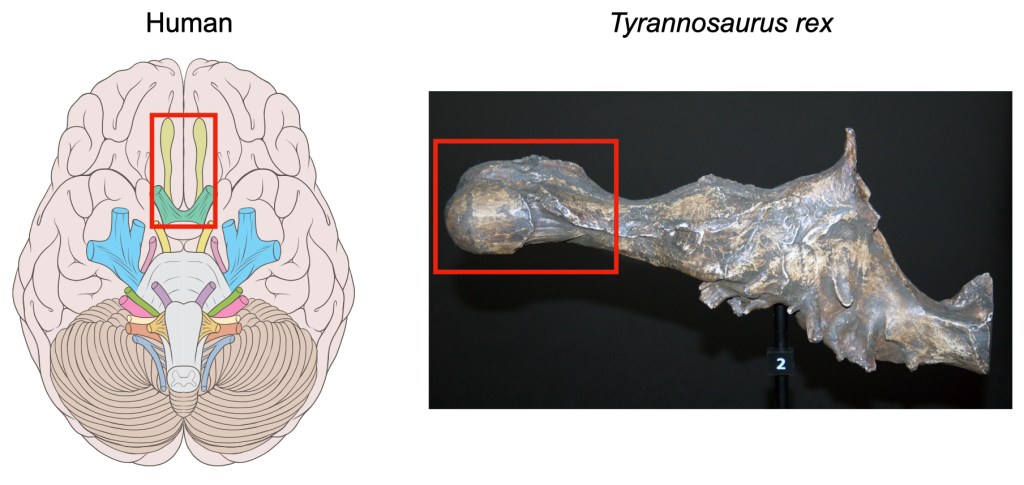

Animals have a specialized part of the brain that reaches down toward the nose, which is responsible for processing molecules in the air and turning them into our sense of smell, called the olfactory bulb (Figure 2). The bigger an animal’s olfactory bulb, the more an animal is thought to rely on smell. Paleoneurologists have used this relationship to make educated guesses about how much different species of dinosaurs relied on smell. For example, Tyrannosaurs had relatively large olfactory bulbs and are thought to have used smell when scavenging, whereas other dinosaurs like Oviraptorosaurs and Ornithomimisaurs have smaller olfactory bulbs and are thought to have relied more heavily on sight, similar to modern birds2. Understanding a dinosaur’s sense of smell gives information not only about how much they may have used smell to hunt, but whether they could have used smell to recognize kin or engage in paternal/maternal behaviors, giving insight into social structure.

Inner ear

Another reliable marker is the size of small structures in the inner ear. Specifically, the shape of a group of structures that aid in maintaining balance and spatial orientation, called the semicircular canals (Figure 1, right, red), can give insights into how a dinosaur moved2, such as whether they were restricted to walking and running on the ground or could fly. For example, the shape and size of the semicircular canals suggest that Tyrannosaurus rex was limited to the ground, but some dinosaurs related to Velociraptor may have been able to glide through the air (although not to the same degree as modern birds)1.

Also of interest is a thin structure that vibrates when sound waves enter the ear to allow us to perceive sound at different frequences, called the cochlea. The longer the cochlea, the higher the frequency an animal can perceive. Cochlear length can not only indicate what frequencies a dinosaur could hear, but in some cases, it can give hints about other things like social behavior. For example, the common ancestor of crocodiles and birds evolved a longer cochlea. This makes sense for bids, as they use high-pitched songs to communicate, but crocodiles, who can only communicate via low-pitched grunts, were more of a mystery. However, unlike other reptiles, crocodiles care for their young, so the longer cochlea may have allowed crocodilian ancestors to hear their high-pitched chirps1,8.

Eyes

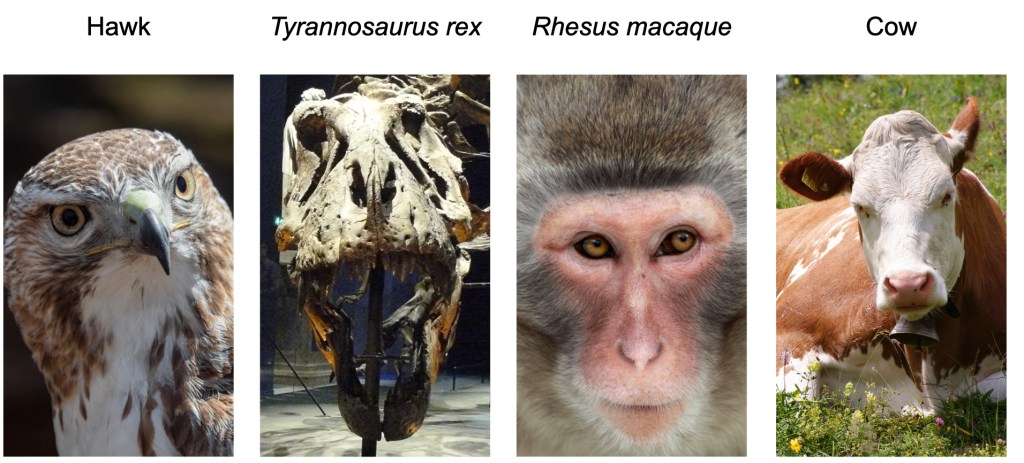

Just like brains, dinosaur eyes aren’t preserved for millions of years, but some of their features can be determined from their skulls. For example, for many animals with two eyes, both eyes view overlapping parts of the world. This overlap is called the binocular field (you can test this by alternately closing each eye and observing how much of the same thing you see in each eye alone). Eyes that are front-facing and closer together tend to have larger binocular fields. Animals with larger binocular fields, like humans and birds, have better depth perception than animals with smaller binocular fields, like cows (Figure 3). Dinosaurs like Tyrannosaurus and Velociraptor had two front-facing eyes that were close together, suggest that their depth perception was similar to or even better than modern birds of prey like hawks9. Understanding a dinosaur’s depth perception can help paleoneurologists guess at what kinds of hunting styles they may have used.

Many dinosaurs also have a flimsy bone-like structure in their eye that controls how much they can open their pupils to let in light, called a sclerotic ring (Figure 4). It is hard to find fossils that have the sclerotic ring preserved, but when we do, combining that information with the relative size of the eyes can tell us about whether a dinosaur was likely nocturnal (awake at night) or diurnal (awake during the day). Specifically, animals with larger eyes and sclerotic rings tend to be awake at night, because they allow the eye to let in more light during the dark hours of the night1,10.

The future of paleoneurology

The field of paleoneurology has made huge advances since the first endocasts were examined in the late 1800s. Until recently, paleoneurologists relied on already existing knowledge from the field of neuroscience to make their conclusions. However, a new study points toward an exciting future for paleoneurology where new neuroscience experiments might be performed to make insights into dinosaur brains11.

In this study, researchers wanted to see if changes in brain shape that they observed in endocasts might give hints as to when the earliest bird ancestors began to fly. To address this question, they measured brain activity across the brains of flying pigeons to determine what kind of brain activity is associated with flight. Once they identified which parts of the brain were active while the birds were in flight, they went back to see whether the endocasts of their evolutionary ancestors show any indications of these brain regions being enlarged compared to even older dinosaurs. While paleoneurologists won’t always need to conduct new neuroscience experiments to apply insights to dinosaur brains, it’s exciting to think that modern-day neuroscientists can conduct experiments today to teach us about our long-extinct cousins.

Paleoneurology shows us that neuroscience isn’t just insightful for living brains. We’ll never know for sure if a dinosaur’s favorite music is jurclassic or if their laughter was pre-hysterical (sorry, I’m not sorry), but there’s still a lot we can learn with clever insights and careful measurements. And while dinosaurs may have gone extinct millions of years ago, the field of paleoneurology is alive and thriving.

If you enjoyed learning about paleoneurology, you might also enjoy reading about Tilly Edinger, who played a key role in founding the field in the early 1900s. Her 1929 book, “Die fossilen Gehirne” (“Fossil brains”), summarized 280 papers about the brain and spinal cords of extinct animals and drew connections between them for the first time. Aside from her prolific scientific contributions, Edinger was also the first woman to be elected president of the Society of Vertebrate Paleontology and overcame incredible obstacles living as a Jew in Nazi Germany.

References

1. Ksepka, A. M. B., Daniel T. Dinosaur Brain Science Is Revealing the Senses of T. rex and Its Prey. Scientific American https://www.scientificamerican.com/article/how-did-dinosaurs-see-smell-hear-and-move/ (2024).

2. Balanoff, A. M. Dinosaur palaeoneurology: an evolving science. Biol. Lett. 20, 20240472 (2024).

3. Lauters, P., Vercauteren, M., Bolotsky, Y. L. & Godefroit, P. Cranial Endocast of the Lambeosaurine Hadrosaurid Amurosaurus riabinini from the Amur Region, Russia. PLoS ONE 8, e78899 (2013).

4. Jerison, H. J. Brain Evolution and Dinosaur Brains. Am. Nat. 103, 575–588 (1969).

5. Labra, N. et al. What do brain endocasts tell us? A comparative analysis of the accuracy of sulcal identification by experts and perspectives in palaeoanthropology. J. Anat. 244, 274–296 (2024).

6. Jerison, H. J. Allometric Analysis of Brain Size. in Encyclopedia of Neuroscience 239–244 (Elsevier, 2009). doi:10.1016/B978-008045046-9.00944-X.

7. Watanabe, A. et al. Are endocasts good proxies for brain size and shape in archosaurs throughout ontogeny? J. Anat. 234, 291–305 (2019).

8. Hanson, M., Hoffman, E. A., Norell, M. A. & Bhullar, B.-A. S. The early origin of a birdlike inner ear and the evolution of dinosaurian movement and vocalization. Science 372, 601–609 (2021).

9. Stevens, K. A. Binocular vision in theropod dinosaurs. J. Vertebr. Paleontol. 26, 321–330 (2006).

10. Choiniere, J. N. et al. Evolution of vision and hearing modalities in theropod dinosaurs. Science 372, 610–613 (2021).

11. Balanoff, A. et al. Quantitative functional imaging of the pigeon brain: implications for the evolution of avian powered flight. Proc. R. Soc. B Biol. Sci. 291, 20232172 (2024).

Cover photo by amelia sal sabila from Pixabay with brain-1 icon by Servier.

Figure 1 includes images by Matt Martyrniuk on Wikimedia Commons, image from Sereno et al. (2007) from Wikimedia Commons, and part of Figure 1 from Lauters et al. (2013) on PlosOne.

Figure 2 includes images by Patrick J. Lynch on Wikimedia Commons, and Matt Martyrniuk on Wikimedia Commons.

Figure 3 includes images by Rhododendrites on Wikimedia Commons, Lyokoï on Wikimedia Commons, Alfonsopasphoto on Wikimedia Commons, and Kim Hansen on Wikimedia Commons.

Figure 4 is image by Eduard Solà Vázquez on Wikimedia Commons.

Leave a comment