February 3rd, 2025

Written by: Eve Gautreaux

Still keeping up with your New Year’s resolutions? If so, you’re doing better than most! You’ve made it past the second Friday in January, sometimes referred to as “Quitter’s Day”, which is the day by which most people have quit their New Year’s resolutions. In fact, a survey of 1,000 U.S. adults who made a New Year’s resolution found that only 1% kept their resolution by the end of the year.

So why are resolutions so hard to keep? Are we simply creatures of habit, and if so, what makes forming new habits and breaking ‘bad’ habits so difficult for our brains? To answer this question, we first need to understand what exactly a habit is and where it comes from.

What is a habit?

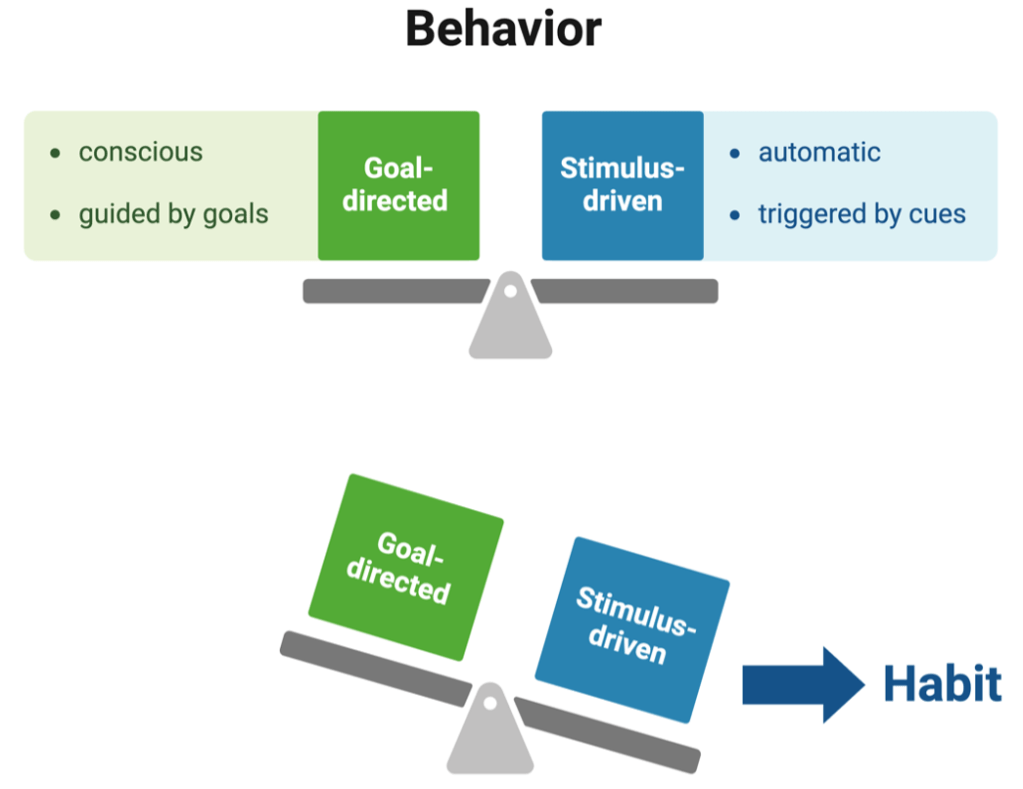

Our behavior is controlled by a balance of two systems: a goal-directed system and a stimulus-driven system1 (Figure 1). The goal-directed system consciously and intentionally guides behavior based on goals and assessment of possible outcomes. For example, you consciously decide to email your boss based on a goal, which is to let her know you need to reschedule your meeting for next week.

Meanwhile, the stimulus-driven system automatically triggers behavior based on familiar cues and contexts1. For example, your alarm clock goes off and, without even thinking, you walk to the kitchen to make a cup of coffee like you do every other morning. Habits are expressed when the stimulus-driven system outweighs the goal-directed system.

Therefore, a habit is defined as a behavior triggered by cues that is developed through repetition and persists regardless of current beliefs and goals2. In other words, habits are things we do repeatedly that are relatively unconscious and automatic. This includes anything from tapping your foot or biting your nails to saving 20% of your paycheck or going to the gym every Tuesday. Importantly, habits are not limited to actions, they can also be thoughts. For example, planning your to-do list when you are trying to fall asleep each night or making a mistake and reflexively thinking something negative are both thought habits.

If you’re like me, you may be thinking “back up, going to the gym is NOT automatic for me”. First of all, touché. Second of all, it could be. I don’t mean this in a toxic-positivity-motivational-quote-peptalk way, but rather in that oftentimes—although not always—habits begin as conscious, intentional behaviors using the goal-directed system1. So how exactly does a behavior—goal-directed or otherwise—actually develop into a habit?

Where do habits come from?

The recipe for habit formation includes two key ingredients: repetition and reward.

A stimulus is any detectable change in a state2; this could be a light, a certain setting or location, a song you hear, an emotion you feel, or your stomach growling. These stimuli can act as cues that cause a behavior in response to the stimuli. For example, the light causes you to cover your eyes, feeling nervous causes you to bite your nails, and your stomach growling causes you to open the fridge to search for a snack.

When neurons in the brain that are responsive to a particular stimulus are active at the same time as neurons associated with a behavior, a connection is formed between the two. Initially, the goal-directed system guides the behavior using a brain region responsible for conscious control and decision-making called the prefrontal cortex3.

With each repetition of this stimulus-response sequence, the connection is strengthened. As the connection becomes stronger, the stimulus-driven system takes over via a group of brain structures called the basal ganglia that act as a hub to seamlessly coordinate the stimulus-behavior sequence, making it more automatic3. Think of this as our brains forming a shortcut.

So, repetition leads our brains to form shortcuts, but what leads to repetition in the first place? Repetition typically happens as a consequence of reward. We are wired to seek out things that feel good and avoid things that feel bad, both of which are rewarding. Dopamine is a chemical in the brain that is released when we experience something rewarding3. Dopamine acts as feedback, chemically “tagging” a behavior for repetition and thereby reinforcing it (Figure 2).

This automation (stimulus-driven system) reduces the amount of effort and conscious thought (goal-directed system) needed to perform the behavior2. Conscious control and decision-making require a lot of energy and resources. In this way, habits serve to reduce the workload for our brain, allowing those resources and energy to be used elsewhere. Habits are our energy-saving autopilot.

However, not everything that feels good is good for us and not everything that feels bad is bad for us. So how can we hack this system to create ‘good’ habits and break ‘bad’ habits?

Factors that affect habit expression

As mentioned previously, habits occur when the stimulus-driven system outweighs the goal-directed system. This can result from strengthening the stimulus-driven system, weakening the goal-directed system, or both.

Energetically expensive conditions

Conditions such as time pressure, stress, distraction, critical thinking, and sleep-deprivation all weaken the goal-directed system by stealing away physical, mental, or emotional energy and resources that are necessary for the conscious and intentional guidance towards goals2. In fact, brain scans revealed that regions linked to the goal-directed system are less active under these conditions while regions linked to the stimulus-response system are more active2.

Habits help give you one less thing to critically think about, which reduces demands and makes your life easier. This is one reason why breaking habits is so hard! Under the conditions of stress, distraction, sleep-deprivation, or high mental demands we are more likely to slip into habits to lighten our load and conserve energy.

Likewise, these conditions make forming new habits hard. Before a new habit becomes a habit, it requires the goal-directed system, which is weaker when we are experiencing energetically-expensive conditions.

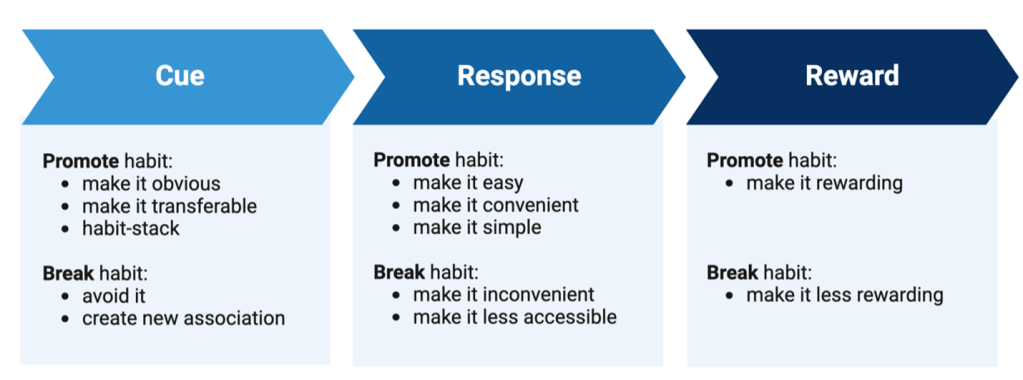

Applying this logic, if you want to form a habit, make it less demanding and mentally taxing. Make it easy! “Easy” means convenient and simple. For example, if you want to start exercising more, don’t join the gym across town, join the one on your commute route to work or do at-home workouts. This is convenient. If you want to take better care of your skin, don’t give yourself a 15-step skincare routine, start with two products. This is simple.

Likewise, if you want to break a ‘bad’ habit, weaken the stimulus-driven system. Make your autopilot unavailable. This consists of making a behavior less convenient and accessible. Add time limits on your screen time or keep your phone in another room altogether to prevent doomscrolling.

Habits are context-dependent

The ideal conditions for a strong habit are a consistent environment with reliable reinforcement2. This is because a predictable environment and outcome once again reduces the need for conscious control and attention to execute the behavior, allowing the brain to go on autopilot.

This is another reason why forming a habit is so hard! Life—which is to say our environment—is constantly changing.

Applying this information, to promote the formation of a habit try the following:

- Choose a cue or context that is highly transferable. If you want to run more, have the cue be your running shoes by the door. In theory, your shoes shouldn’t shapeshift and there should always be a door somewhere. So even if you are traveling for work or move across the globe, your cue and context can transfer with you.

- Make the cue obvious4. Make the cue visible and impossible to miss. If you want to start journaling every night, leave your journal on your pillow in bed. You should notice this unless you like very firm, small pillows.

- Use another well-established habit as the cue. This is known as habit-stacking2. It helps you piggyback off of the automaticity of a strong habit. If you are excellent at your habit of watching reality TV every night, try pairing it with a new habit like a stretch routine or cooking a new recipe.

On the other hand, the context-dependent nature of habits is also why breaking a habit is so hard. Many contexts and cues that trigger a behavior are hard to avoid. You can’t (easily) move out of the city full of reminders to avoid going back to your ex. Remember that cues can include emotions too! You can’t exactly force yourself to not feel sad or stressed to avoid mindlessly scrolling on your phone.

An effective approach to break habits includes substituting or replacing the unwanted habit associated with a cue with a new behavior2. Create a new association between the cue and either a neutral or wanted behavior. For example, if stress causes you to bite your nails, try carrying a fidget device with you to occupy your hands instead.

It is worth noting that substitution does not technically overwrite the old stimulus-response connection, but instead creates a new one in our brain2. However, the connection linked with the new behavior can become stronger through repetition, as described earlier, and eventually be favored over the unwanted, now weaker connection.

Now what?

Okay, so now we understand what habits are, how they are formed, and strategies to make or break them. Great! What’s the ETA of the new and improved me? How long will this take?

The answer is anywhere between 18 and 254 days. According to a study of health-related habits, this is the range of time it took participants to reach automatic engagement in the new habit, with a median of 66 days2. Why such a wide range of time?

Well, to put it simply, it’s complicated. First, it is important to note that the number of repetitions and the amount of time it takes to change a habit are two different things2. For example, repeating a behavior 100 times over the course of one day likely does not have the same effect as repeating a behavior once per day for 100 days.

The complexity of the habit itself also influences the rate of change. Flossing your teeth every night may only take a couple weeks to adopt, while establishing a gym routine may take months or longer before truly becoming habitual.

Additionally, there are numerous individual differences. We all differ not only in personality, strengths, weaknesses, and biology, but also in motivation. The level as well as the type of motivation we feel can vary greatly depending on the habit and life factors.

If there is one message you take from this article: be kind to yourself. The fact that there is a body of research over the span of decades dedicated to studying habits and even a “Quitter’s Day” in honor of breaking them means that not only are you not alone in your struggle for change, but it is safe to say that it is human nature.

References

1. Gera, R. et al. Characterizing habit learning in the human brain at the individual and group levels: A multi-modal MRI study. Neuroimage 272, 120002 (2023).

2. Buabang, E. K., Donegan, K. R., Rafei, P. & Gillan, C. M. Leveraging cognitive neuroscience for making and breaking real-world habits. Trends Cogn. Sci. 29, 41–59 (2025).

3. (PDF) The Neuroscience of Habit Formation.

4. Clear, James. (2018). Atomic Habits: an easy & proven way to build good habits & break bad ones (PDF ed.). New York: Avery.

Cover photo by storyset on Freepik.

Figures 1, 2, and 3 created with Biorender by Eve Gautreaux.

✅ I really appreciated this breakdown of how our brains form habits—especially the section about stress pushing us into autopilot by shifting balance between goal-directed and habitual behavior . I had a similar realization when I read Atomic Habits: the theory was solid, but real-world application felt impossible—especially under stress or decision fatigue.

Taking a free Archetype6 quiz showed me I’m a Synthesizer, which clarified why I was constantly iterating systems instead of sticking with them. Three takeaways that helped me shift:

I’m experimenting with a “stress buffer” habit—like journaling one line when things feel chaotic—but I’m not sure how long it takes before it actually offsets stress-induced autopilot. Has anyone tracked that kind of buffer habit before?

LikeLike