September 3rd, 2024

Written by: Margaret Gardner

Most of us – doctors, patients, the general public – tend to think of our minds and our bodies as distinct. Mental and physical problems are often treated by different doctors. The philosopher Descartes earned his place in history books with the invention of mind-body dualism, the idea that the mind is separate from the physical body1. We watch movies like Freaky Friday and Face/Off in which people’s minds and personalities are neatly separated from their physical form. However, new research is starting to show many ways that our mental health is affected by our physical health and vice versa. In a series of recent studies, a research group at The University of Melbourne led by Dr. Ye Ella Tian shine a light on this connection and how important it is for doctors to treat their patients’ minds, brains, and bodies.

Brain or Body? The problem is both.

If you ask a doctor what distinguishes someone with a mental illness, like anxiety or schizophrenia, from someone without any psychiatric diagnoses, they might tell you about differences in their brain chemistry, function, or structure. However, even after decades of learning about the brain’s relationship with disease, we’re still far from a complete, practical understanding of how to cure mental illnesses. Which begs the question: with brain scans and cognitive tests gobbling up researchers’ and doctors’ attention, are we missing important information outside the skull?

This is exactly what Dr. Tian found in a study of nearly 18,000 adults, about half of whom were diagnosed with schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, depression, and/or anxiety2. Her team wanted to see whether individuals with mental illness experienced more physical health problems than those who did not, and whether specific symptoms were more common among those with particular psychiatric diagnoses. First, they looked at results from blood and urine tests, physical exams, and brain scans in individuals without psychiatric illnesses to define a “healthy” range. Then, they combined measurements related to the same body systems – for instance, combining the cholesterol value with blood pressure and other measures related to heart health. This allowed them to score the health of every individual’s heart, lungs, musculoskeletal system, immune system, kidneys, liver, metabolism, brain gray matter, and brain white matter, while accounting for age and sex. Finally, they tested whether body health scores differed between individuals with or without a psychiatric diagnosis and identify which measures more accurately predicted who does or does not have a mental illness: brain or body health.

This study revealed that those with psychiatric diagnoses had significantly lower scores for every body system measured, indicating that they were less physically healthy than those without mental illness. Even more surprising was that physical health scores were better predictors of mental illness status than the two brain health scores; for example, the mathematical model using physical health scores was able to correctly determine if someone had depression 67% of the time, while the brain score model was only correct 58% of the time. In short, even though conditions like schizophrenia and bipolar disorder are caused by issues in the brain, peoples’ bodies actually tend to be more “unhealthy”.

The chicken, the egg, or something else?

You might read this and think “Well, throw away the MRI scanner. Clearly, looking for signs of disease in the brain is a colossal waste of time”. Well, there are a few caveats. For one, there are newer, morse sensitive technologies being developed to study the brain in much greater detail than the brain structure measures used in this study. Thus, it’s very possible that measures of brain function or some yet-to-be-invented brain scan might do an even better job than physical health measures at classifying mental illness. Second, the brain measures used in this study did the best job of distinguishing individuals with different psychiatric disorders from one another, which is important since the treatment for anxiety is very different from the treatment for schizophrenia. But most importantly, this study just shows that there is an association between physical and mental illness, not which one came first.

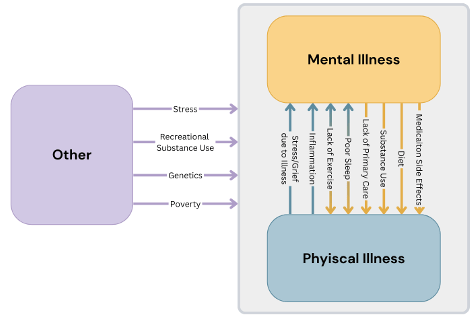

We know from years of research that body and brain health affect each other in a lot of complicated ways (Figure 1). Some might be more easily traceable – for instance, many medications used to treat schizophrenia have side effects that include severe weight gain or heart problems3. Others are more complicated, like the theory that an overactive immune system can cause problems like depression4.

In a follow-up study, Dr. Tian and her colleagues worked to disentangle some of these messy possible pathways between physical and mental health5. In a large subset of data from the first study, they attacked the chicken or the egg issue. To do this, they tested: 1) whether lifestyle and environmental factors like poor sleep or alcohol use increase the risk for depression and anxiety indirectly by worsening physical health, and 2) if poorer physical health in turn increases depression and anxiety risk directly or by way of brain structure changes. Their results suggest that many of the associations found in the first study between physical and mental illness were partially explained by the effects of different organ systems on brain structure. For example, they found while poor lung scores did directly influence depression, it also had just as strong of an influence via it’s effects on brain health; in other words, if you could prevent lung diseases effects on brain structure, then unhealthy lungs would only be half as bad for your mental health. Similarly, over half of heart health’s effect on anxiety symptoms were downstream of to its effects on white matter. They also learned that some lifestyle factors, such as physical activity, affected mental health by way of many body systems, while others, such as smoking, exerted effects via specific aspects of physical health, like lung and musculoskeletal function.

While these kinds of analyses aren’t as definitive as an experiment6, they’re very useful in cases like these where it isn’t ethical to assign some people to smoke and measure if/how it makes them depressed. Also, because the physical health data they used was collected several years before participants’ brain scans and mental health assessments, they couldn’t test the reverse direction, how mental health impacts the physical body (i.e. the yellow arrows in Figure 1). However, these results do at least support the existence of a brain-body connection that environmental factors can hijack to disrupt mental health.

So now what?

Collectively, this work has important implications for how we treat individuals suffering from mental illnesses. First, the strong associations between physical health problems and psychiatric disorders uncovered in the first study makes it very clear that physical health is a big problem that we can’t ignore when treating and researching mental illnesses. First and foremost, this is important for helping real people who are more than just brains floating in a jar. In addition, the second study shows that improving physical health with things like access to healthy foods may set off a domino effect that results in improved mental health, too. So, while we still have a long way to go in understanding exactly how the brain and body affect how we think and feel, it’s not too early for therapy clinics to start offering yoga classes or encouraging regular PCP visits.

Want to learn more about the brain-body connection? Check out these other PNK articles on the gut’s microbiome, smoking, depression and the immune system, exercise, dental hygiene, heart rate, diet, and sleep.

References

1. Mind-body dualism | Definition, Theories, & Facts | Britannica. August 26, 2024. Accessed August 29, 2024. https://www.britannica.com/topic/mind-body-dualism

2. Tian YE, Di Biase MA, Mosley PE, et al. Evaluation of Brain-Body Health in Individuals With Common Neuropsychiatric Disorders. JAMA Psychiatry. 2023;80(6):567-576. doi:10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2023.0791

3. Dayabandara M, Hanwella R, Ratnatunga S, Seneviratne S, Suraweera C, de Silva VA. Antipsychotic-associated weight gain: management strategies and impact on treatment adherence. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 2017;13:2231-2241. doi:10.2147/NDT.S113099

4. Nettis MA, Pariante CM. Is there neuroinflammation in depression? Understanding the link between the brain and the peripheral immune system in depression. Int Rev Neurobiol. 2020;152:23-40. doi:10.1016/BS.IRN.2019.12.004

5. Tian YE, Cole JH, Bullmore ET, Zalesky A. Brain, lifestyle and environmental pathways linking physical and mental health. Nat Ment Health. Published online August 9, 2024:1-12. doi:10.1038/s44220-024-00303-4

6. Bollen K, Pearl J. Eight Myths About Causality and Structural Models. Published online April 1, 2012. Accessed August 31, 2024. https://papers.ssrn.com/abstract=2343821

Figure 1 made by Margaret Gardner in Canva.

Photo credit: Peter_Middleton, Pixabay.

Leave a comment