April 2nd, 2024

Written by: Lisa Wooldridge

If you’ve ever had surgery, you may have been given a painkiller like morphine, Vicodin, or Percocet afterwards. These medications all belong to a group of chemicals called opioids, which are probably the most effective pain-relieving medications we have for short-term, severe pain. You may have also seen opioids in the news for a much scarier reason. Each year, thousands of Americans die after overdosing on opioid drugs. In 2022, opioid drugs caused or contributed to more than 82,000 deaths in the United States, accounting for nearly three-quarters of all drug deaths in the nation.1 How can one type of drug have so much medical value, but still be so dangerous?

What is an opioid? How can opioids have such different effects all at once?

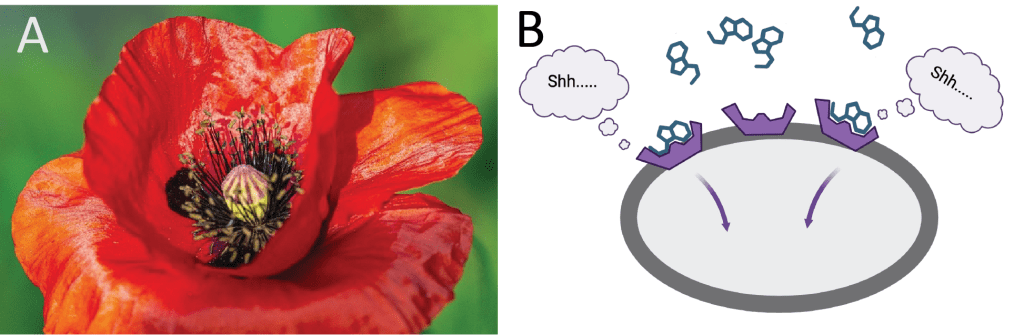

Opioidsare chemicals that come from the opium poppy plant (Figure 1A), or that have similar effects on our body as those that do. Specifically, opioids share a shape that fits into opioid receptors. Receptors are a kind of cellular machinery that sit on the surface of cells and communicate messages from the outside world (Figure 1B). In the case of opioids and their receptors, that message is: “quiet down!”2

When you take an opioid, it is absorbed by your bloodstream and circulated throughout your whole body. Whenever it comes in contact with opioid receptors on a cell, it will fit into that receptor and send the “quiet down!” message. Cells in many different organs through our body have opioid receptors, such as the intestines, the brain, and the liver. Even a single type of opioid can quiet down the cells located in all these different organs, creating their vast array of different effects. Some are desirable; others are undesirable.

Opioid receptors are found throughout the nervous system –in the brain, the spinal cord, and in the nerves located in the rest of our body that sense the world around us.2 It is through opioid’s actions in the nervous system that they can relieve pain and cause intense pleasure. But it is also through opioid receptors in the nervous system that these drugs can have their most dangerous undesirable effect – disrupting breathing.

This is not to say that it is never a good idea to use opioid drugs. At the relatively low doses typically prescribed for short-term pain relief, they can be a safe and effective option despite some risks. But the more someone takes, the more likely they will experience dangerous effects. Or, as drug scientists love to say, the dose makes the poison. The required dose to reach that point differs dramatically depending on the exact opioid, but any opioid can be dangerous at a high enough dose. For this reason, overdose deaths are most likely to occur when the drugs come from an unregulated source, where the dose or even the exact opioid might not be clear.3

How do opioids relieve pain?

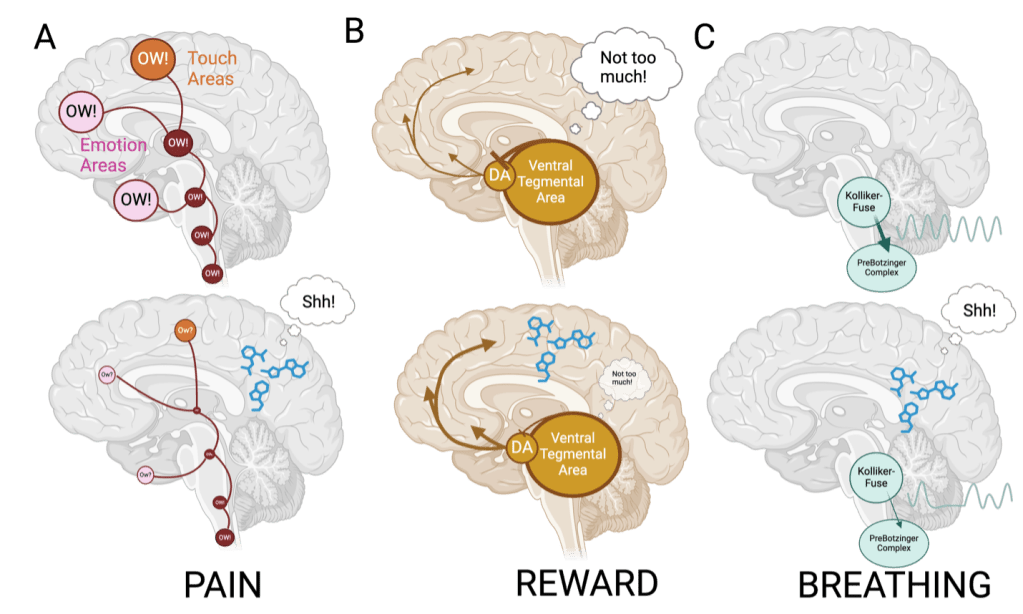

Pain is an unpleasant sensation and emotional experience we have in response to dangerous things in our environment – think stepping on a pin, putting your hand on a hot stove, or even a surgical incision. The initial sensation of pain will start in specialized nerve cells called nociceptors, which are particularly tuned to sense things in the environment that can hurt us. Nociceptors are the first step in a chain of messages from cell to cell, passing that message – “OW!” — first through nerves, then up through the spinal cord, through a maze of brain areas, and finally to the areas of our brain that process our emotions and our sense of touch (Figure 2A).2 Only then do we feel the entire sensory and emotional experience of pain.

Opioid receptors can be found at almost every step of the message’s route, so opioid drugs can quiet the pain message at any step(s) along the path from the body to the brain.2 This is why opioids are such effective painkillers.

Why do opioids make us feel so good?

Dopamine is thought to be responsible for making us feel good in response to things we like — delicious food, social contact with a friend or partner, winning money, and taking certain drugs – including opioids.4,5 Dopamine production occurs in only a handful of locations throughout the brain, including one small spot tucked into the middle of the brain called the ventral tegmental area. When we encounter something we like, certain cells from the ventral tegmental area send dopamine messages to the front of the brain. The more dopamine in that message, the better we end up feeling.6 There are other types of cells in the ventral tegmental area, too. Some of these cells put the brakes on the dopamine cells, restraining the message.

Opioid receptors are found in the ventral tegmental area. But instead of quieting down dopamine messages, opioids cause them to surge!4,5,6 That’s because opioid receptors are not on the dopamine message cells, but instead on the cells that put on the brake7. By quieting down these cells instead, opioids release the brakes on the dopamine message (Figure 2B). The resulting unrestrained message is thought to explain the intense feelings of pleasure that some opioid users experience.4,6

Why do opioid overdoses occur?

We’ve already discussed why the dose makes the poison. And indeed, while opioids have many desirable effects, at high doses they can profoundly disrupt breathing, often fatally so.1 In fact, breathing disruption is the main reason that opioid overdoses can be fatal.

When you think of breathing, you probably think about your lungs. But the nervous system also plays a key role in breathing. Opioid receptors in a part of the brain called the brainstem are probably the culprit for the drugs’ breathing disruptions. Two brainstem areas that control breathing are particularly packed with opioid receptors. The first is called the PreBötzinger complex, and it produces a steady breathing rhythm for us in response to how much oxygen we are using.8 The second area is called the Kolliker-Fuse nucleus, and its activity keeps that rhythm steady (Figure 2C). Together, they work together to make sure we are taking in enough oxygen to keep us alive and feeling good.

Since both the PreBötzinger complex and the Kolliker-Fuse nucleus are packed with opioid receptors, opioids can easily quiet these cells down. Then, not only do opioids make it hard for the PreBötzinger complex to sense how much oxygen we’re using and create the appropriate rhythm, it also makes it hard for the Kolliker-Fuse nucleus to stabilize this rhythm.8 This leaves us susceptible to disrupted breathing.

Opioids have many faces – they can provide potent pain relief, powerful pleasure, and, at high enough doses, breathing disruption that can be life-threatening. While we’ve talked about these various opioid effects in isolation, they don’t occur entirely independently. The experience of taking opioids will include all three effects at once, whether we recognize it or not. Think of how amazing it feels to put cool ointment on a burn or a warm compress on an aching muscle. Or how the slow, deep breathing of Lamaze training can help a mother get through the pain of childbirth.9 Indeed, it is probably the intermingling of opioids’ effects on pain, pleasure, and breathing that make them so effective at relieving our pain.

References

- Ahmad FB, Cisewski JA, Rossen LM, Sutton P. Provisional drug overdose death counts. National Center for Health Statistics. 2024.

- Corder G, Castro DC, Bruchas MR, Scherrer G. Endogenous and Exogenous Opioids in Pain. Annu Rev Neurosci. 2018 Jul 8;41:453-473. doi: 10.1146/annurev-neuro-080317-061522. Epub 2018 May 31. PMID: 29852083; PMCID: PMC6428583.

- Tanz LJ, Gladden RM, Dinwiddie AT, et al. Routes of Drug Use Among Drug Overdose Deaths — United States, 2020–2022. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2024;73:124–130. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.15585/mmwr.mm7306a2

- Di Chiara G, Imperato A. Drugs abused by humans preferentially increase synaptic dopamine concentrations in the mesolimbic system of freely moving rats. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1988 Jul;85(14):5274-8. doi: 10.1073/pnas.85.14.5274. PMID: 2899326; PMCID: PMC281732.

- Lewis RG, Florio E, Punzo D, Borrelli E. The Brain’s Reward System in Health and Disease. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2021;1344:57-69. doi: 10.1007/978-3-030-81147-1_4. PMID: 34773226; PMCID: PMC8992377.

- Martinez D, Slifstein M, Broft A, Mawlawi O, Hwang DR, Huang Y, Cooper T, Kegeles L, Zarahn E, Abi-Dargham A, Haber SN, Laruelle M. Imaging human mesolimbic dopamine transmission with positron emission tomography. Part II: amphetamine-induced dopamine release in the functional subdivisions of the striatum. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2003 Mar;23(3):285-300. doi: 10.1097/01.WCB.0000048520.34839.1A. PMID: 12621304.

- Galaj E, Han X, Shen H, Jordan CJ, He Y, Humburg B, Bi GH, Xi ZX. Dissecting the Role of GABA Neurons in the VTA versus SNr in Opioid Reward. J Neurosci. 2020 Nov 11;40(46):8853-8869. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0988-20.2020. Epub 2020 Oct 12. PMID: 33046548; PMCID: PMC7659457.

- Varga AG, Reid BT, Kieffer BL, Levitt ES. Differential impact of two critical respiratory centres in opioid-induced respiratory depression in awake mice. J Physiol. 2020 Jan;598(1):189-205. doi: 10.1113/JP278612. Epub 2019 Nov 2. PMID: 31589332; PMCID: PMC6938533.

- Kaple GS, Patil S. Effectiveness of Jacobson Relaxation and Lamaze Breathing Techniques in the Management of Pain and Stress During Labor: An Experimental Study. Cureus. 2023 Jan 1;15(1):e33212. doi: 10.7759/cureus.33212. PMID: 36733553; PMCID: PMC9887925.

Cover image from Pixabay.com user CDD20

Figure 1A image from Pixabay.com user rudibavera

Figures 1B and 2 created with Biorender.com