July 4th, 2023

Written by: Vanessa Sanchez

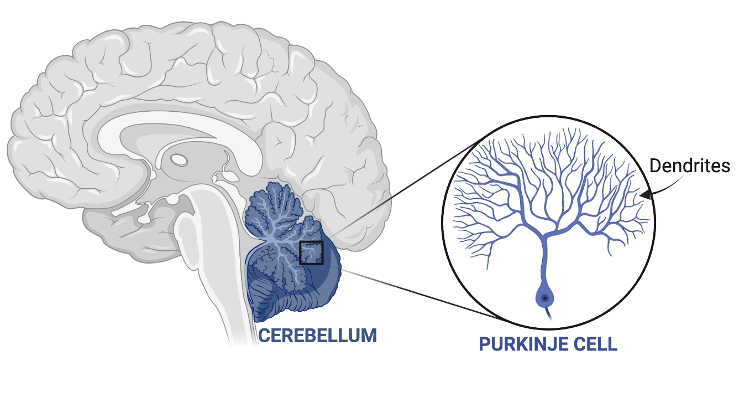

As you walk, balance on one foot, or ride a bike, each movement is tightly controlled by a brain region called the cerebellum. The cerebellum is located at the back of the brain (Figure 1) and is small but mighty. Because it is so small, the cerebellum got its name from the Latin for “little brain”, but it is actually home to over 80% of all the neurons in the whole brain1-2! One of the many types of neurons found in the cerebellum is the Purkinje cell.

What are Purkinje cells?

Purkinje cells are unique neurons specific to the cerebellum and are known for how large and intricate their dendritic trees are (Figure 1 arrow). These dendritic trees or branches are what allow neurons to make new synapses with other neurons. Synapses are how neurons communicate between other neurons and cells. The more intricate or complex a neuron’s dendritic branch is, is also a reflection of how many connections that neuron has. Put simply, more branches equals more communication while less branches equals less communication between neurons. In the case of the cerebellum, Purkinje cell dendritic branches are important for allowing it to communicate with the rest of the brain to send information back and form to coordinate movement.

Even though these neurons appear mighty in size, they are particularly vulnerable to any toxic exposure (e.g., drugs or alcohol abuse), brain injury or even disease, which can ultimately lead to their death8-10. While disturbances to the cerebellum have been observed in many brain disorders, one that is particularly interesting is Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD). ASD is a neurodevelopmental disorder that is characterized by a wide variety of behaviors, including, but not limited to, problems with sleep and/or social skills, repetitive behaviors, and nonverbal communication5. Neuroscientists have observed smaller cerebellums and more Purkinje cell death in the brains of patients with ASD who have died, suggesting that there might be a link between ASD and disturbance to the cerebellum3-4. It should be noted that not all people with ASD have Purkinje cell death. Remember, not all people with ASD are the same!

What is the link between Purkinje cell death and autism?

One-way scientists have attempted to answer this question is by studying genes associated with ASD. Two examples of ASD genes are Tsc1 and Bma1, which serve as DNA templates to make important proteins for the cell6-7. Both genes are associated with ASD because any disruption to them can lead to autism. Interestingly, these genes do two different but very important things that are unrelated to the symptoms of ASD. For example, Tsc1 codes for a protein whose job is to prevent tumors from growing meanwhile Bma1 codes for a protein that is important for circadian rhythms – our internal clock that helps us wake up or fall asleep. While these are two extremely different proteins, when they are disrupted, they can lead to ASD.

In two studies, scientists used genetic techniques in mice to remove either Tsc1 or Bma1 genes specifically only from Purkinje cells6-7. By removing these two different genes from Purkinje cells in mice, scientists can study how these mice without Tsc1 or Bma1 are different from mice whose genes are intact, as well as determine what role these genes play in contributing to autistic-like behaviors.

One way to test this is by placing mice with either intact or without Tsc1 or Bma1 in Purkinje cells through a variety of tests to measure autistic-like behaviors. For example, they found that mice without Tsc1 or Bma1 performed poorly in interacting with or recognizing other rodents (a way to measure sociability), as well as hyperactivity and excessive grooming (a way to measure repetitive behaviors)6-7. Because the cerebellum plays a role in motor functioning, scientists also tested if mice with intact or without Tsc1 or Bma1 in Purkinje cells displayed problems with motor coordination and balance. Indeed, scientists found that mice without Tsc1 or Bma1 in Purkinje cells displayed motor deficits, such as ataxia6-7. Ataxia is a term to describe problems with balance and coordination8. To learn more about ataxia, check out my previous PNK article!

Ataxia or any problems movement are one of the first signs that there are problems with the cerebellum (i.e., Purkinje cells). This lead scientists to examine if any changes occurred in the cerebellum, such as analyzing the number of Purkinje cells in mice without Tsc1 or Bma1 in comparison to mice with the genes. If the numbers of Purkinje cells in mice without Tsc1 or Bma1 were lower than in mice with the genes, then this means the genes are important in ensuring the Purkinje cells’ survival. The research team found that mice without Tsc1 had fewer Purkinje cells while Bma1 mice still had the same number of Purkinje cells with or without the gene. Instead, scientists found that the dendritic branches of Purkinje cells inmice withoutBma1 mice were smaller, suggesting that Purkinje cells had problems forming synapses and communicating with other neurons6-7. What this means is that even though Purkinje cells do not have Bma1, they’re still alive but they can’t communicate as well as neurons in mice who have Bma1 intact.

In short, two different genes that are associated with ASD when removed from Purkinje cells in mice can lead to differences in development and survival which ultimately can contribute to autism.

Can protecting Purkinje cells prevent symptoms of ASD?

Scientists gave mice without Tsc1 or Bma1 in Purkinje cellstwo different types of drugs that are known to benefit neuronal health6-7. They speculated that these drugs could protect Purkinje cells from dying by keeping them healthy and alive, which should prevent ASD symptoms. Indeed, they found that mice without Tsc1 or Bma1 who got the drugs had healthy Purkinje cells and did not display autistic-like behaviors similar to mice with Tsc1 or Bma1 intact.

In summary, by studying two different genes associated in ASD in Purkinje cells, scientists were able to understand how they contribute to ASD symptoms like challenges with social skills and repetitive behaviors. Most importantly, these types of studies are what allow scientists to continue to understand the diverse functions of the cerebellum (and other brain regions too!), especially in its role outside of motor control. Scientists are continuing to study whether drugs that prevent ASD-like behaviors in mice could do the same for humans’ treatment for ASD, so keep an eye out for what they discover next!

References

- Van Essen, D. C., Donahue, C. J., & Glasser, M. F. (2018). Development and evolution of cerebral and cerebellar cortex. Brain, behavior and evolution, 91, 158-169.

- Hodos, W. (2009). Evolution of cerebellum. Encyclopedia of neuroscience, 1240-1243.

- Fetit, R., Hillary, R. F., Price, D. J., & Lawrie, S. M. (2021). The neuropathology of autism: A systematic review of post-mortem studies of autism and related disorders. Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews, 129, 35-62.

- Amaral, D. G., Schumann, C. M., & Nordahl, C. W. (2008). Neuroanatomy of autism. Trends in neurosciences, 31(3), 137-145.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2019). Signs and symptoms of autism spectrum disorders. Centers for Disease Control. Last reviewed March 28, 2022.

- Liu, D., Nanclares, C., Simbriger, K., Fang, K., Lorsung, E., Le, N., … & Cao, R. (2022). Autistic-like behavior and cerebellar dysfunction in Bmal1 mutant mice ameliorated by mTORC1 inhibition. Molecular psychiatry, 1-12.

- Tsai, P. T., Hull, C., Chu, Y., Greene-Colozzi, E., Sadowski, A. R., Leech, J. M., … & Sahin, M. (2012). Autistic-like behaviour and cerebellar dysfunction in Purkinje cell Tsc1 mutant mice. Nature, 488(7413), 647-651.

- What is ataxia? National Ataxia Foundation. (2023, July 2). https://www.ataxia.org/what-is-ataxia/.

- Forrest, M. D. (2015). Simulation of alcohol action upon a detailed Purkinje neuron model and a simpler surrogate model that runs> 400 times faster. BMC neuroscience, 16, 1-23.

- Sarna, J. R., & Hawkes, R. (2003). Patterned Purkinje cell death in the cerebellum. Progress in neurobiology, 70(6), 473-507.

Photo by Sandy Millar on Unsplash