February 17th, 2026

Written by: Kara McGaughey

Many of us experience a near-constant inner voice in our heads, which we use to narrate thoughts, rehearse conversations, and read silently as we scan words —like these— on a page. While we typically use our inner voice to talk to ourselves, recent research suggests that it could be leveraged to help people who have lost the ability to speak with others. In this post, we’ll explore communication technology, how it can be transformed by inner speech, and the ethical implications of tapping into the voice in our heads.

The evolution of communication technology

There are millions of people living with conditions that limit their ability to move and speak, like amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS), stroke, or paralysis.1 It’s been a longstanding priority of researchers and engineers to use available technology to help these individuals feel less isolated by finding ways to preserve or restore their ability to communicate. Stephen Hawking’s communication system is one well-known example. Due to ALS, Hawking lost most of the muscle movement needed for speaking and he communicated with the help of a computer system where a cursor scrolled constantly across letters and words organized on the screen. By pressing a button with his finger, Hawking could stop the cursor and select what he wanted to say. Piece by piece, he assembled sentences, which were then read aloud by a speech synthesizer. As his disease progressed and his hand weakened, Hawking’s system was upgraded to be controlled by subtle movements of his eye and cheek muscles (Video 1). However, these muscles also eventually weakened and even eye-controlled communication became difficult. While revolutionary for helping preserve Hawking’s voice and ability to interact with others, the process of interfacing with the computer was both time consuming (Hawking selected each word one at a time) and required some amount of physical movement, which became increasingly difficult as the disease progressed.

Video 1. A video showing how Hawking scrolled through and used slight movements of his eye and cheek muscles to select text one word at a time using his computer. After selection, each word was assembled into a sentence, which was sent to and read aloud by a speech synthesizer.

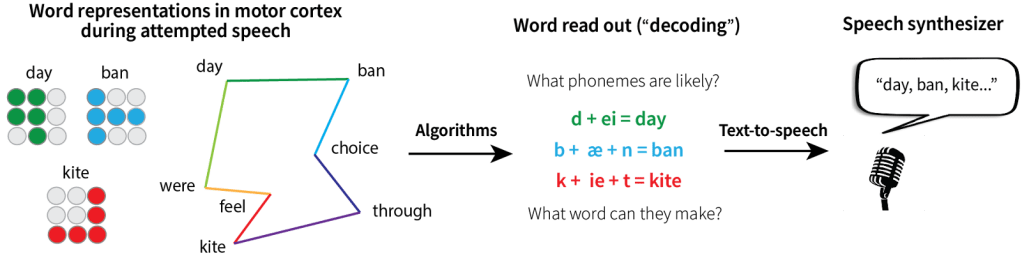

Decades later, a different approach emerged: brain-computer interfaces (BCIs). Rather than relying on button presses or blinks to search through words on a computer screen, these small (think: the height of 15 sheets of paper) surgically-implanted devices record brain activity.2-4 Speech-BCIs work by recording from the brain’s motor cortex —specifically, regions that normally control the muscles involved in speaking such as the lips, jaw, tongue, larynx, and diaphragm.5-6 When we speak, the physical production of each word requires a unique combination of muscle movements, thereby creating distinct patterns of brain activity. For instance, the words “day” and “kite” require different tongue positions, lip shapes, and vocal cord configurations and thus produce different patterns of brain activity in motor cortex. These word-specific patterns of brain activity create a kind of motor “blueprint” that speech-BCIs can be trained to recognize (Figure 1). In one study at UC Davis, a man with ALS named Casey Harrell had a speech-BCI implanted in his motor cortex.7 When Harrell attempted to speak, even though his severe muscle weakness meant the sounds he produced were uninterpretable, the speech-BCI could read out or “decode” his intended words from his brain activity with up to 97.5% accuracy. Like Hawking’s system, Harrell’s BCI preserved his ability to communicate with others. But unlike Hawking’s letter-by-letter selection process, Harrell could produce words simply by attempting to speak them.

However, because speech-BCIs rely on recording and decoding activity in motor cortex associated with the physical act of speaking, they require users to go through the motions of word production. In other words, they must actually attempt to move their lips, cheeks, and tongue. Not only can this be exhausting, but it also means that many patients with progressive diseases will eventually lose the ability to interface with these devices as their condition worsens. This is where inner speech has big potential. Inner speech —the silent mental chatter we use to think, plan, or imagine conversations— doesn’t require any motor movement. If speech-BCIs could read out inner speech the same way they do attempted speech, these devices could help a broader range of patients, like those who are physically unable to attempt speech, and continue working even as progressive diseases advance.

Can BCIs rely on inner speech instead?

Last year, a group of researchers at Stanford University explored whether inner speech could be used to power speech-BCIs.8 They studied four individuals who had speech-BCIs implanted in motor cortex. While these participants had varying degrees of speech and motor deficits, none of them could speak clearly enough to be understood by someone without extensive practice. To build an inner-speech BCI, the researchers would need motor cortex to produce detectable and distinct patterns for different words as participants imagined speaking them. But would it? During inner speech, the mouth, tongue, and vocal cords aren’t actually moving. It wasn’t a given that motor cortex would be active at all, let alone produce patterns of activity distinct enough to decode.

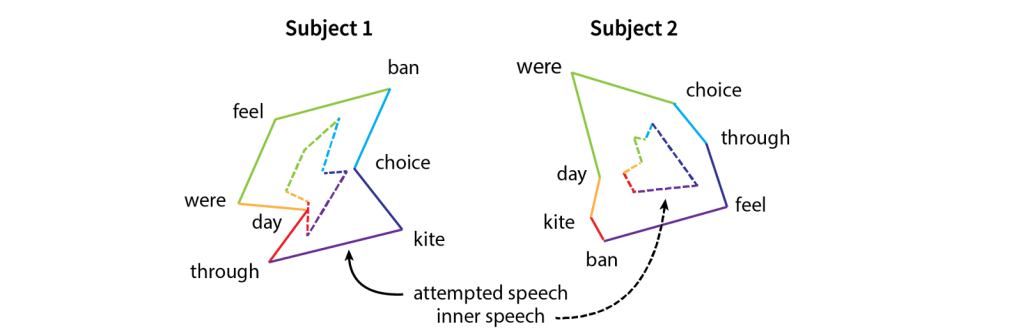

To find out, the researchers designed a task to compare attempted and inner speech. Participants saw a word appear on a computer screen and were instructed either to speak it or to imagine speaking it using their inner voice. Researchers then looked at whether motor cortex showed different patterns of brain activity for each word and whether these patterns were similar between the two conditions. Excitingly, they found that the patterns of activity were similar for attempted and imagined speech. However, the strength varied between conditions with inner speech producing a smaller (i.e., weaker) version of attempted speech —as if the brain plays the same “tune” for each word, but turns down the volume for inner speech. (Figure 2). This shared structure implies that if a BCI can decode attempted speech, it should also be able to decode inner speech.

Knowing that individual words of inner speech are represented in the motor cortex is a tremendous first step, but meaningful communication relies on more than single words in isolation. To be useful, speech-BCIs powered by inner speech need to decode entire sentences in real time. To test this, researchers asked participants to internally speak cued sentences, such as, “That’s probably a good idea,” while their brain activity was decoded in real time (Video 2). While not perfect, the inner-speech BCIs performed remarkably well. When participants imagined speaking sentences constructed from a 50-word vocabulary, the speech-BCI achieved accuracy rates between 67% and 86%. For a 125,000-word vocabulary, accuracy was lower (between 46% and 74%). While the performance of inner speech-BCIs wasn’t perfect, the mistakes they made were often reasonable near-misses much like the kinds of misunderstandings you or I might make when trying to listen to a conversation in a noisy environment. For instance, “I think it has the best flavor” was mistakenly decoded as “I think it has the best player,” reflecting the fact that words that sound similar can be difficult to distinguish.

While decoding inner speech isn’t yet as accurate as decoding attempted speech, these results demonstrate that it’s feasible. As the technology and the decoding algorithms continue to improve, inner-speech BCIs could make communication technology accessible to a much broader range of patients, including those who cannot attempt speech-related movements at all.

What about the privacy concerns raised by tapping into inner speech?

BCIs have always raised ethical questions. For instance, not only does the implantation of BCIs carry surgical risk, but because the brain is so central to who we are, many neuroethicists think that brain-related data has the potential to be revealing in a way that other data may not be.9 With inner-speech BCIs, where scientists face the possibility of decoding private thoughts that were never meant to be communicated, these privacy-related concerns become even more pressing.

The Stanford researchers took these concerns seriously and developed several privacy-protection strategies that would prevent their inner-speech BCI from inadvertently decoding speech users intended to be private. One such strategy was to train their algorithm to only begin decoding when it is “unlocked” by a particular keyword (like, “Hey, Siri!”). Using one participant, the researchers tested how well the inner-speech BCI detected this keyword and found that the accuracy was over 98%. By demonstrating that privacy protections can be built into inner-speech BCIs from the start, this work shows that it’s possible to make these devices more accessible while maintaining respect for users’ mental autonomy. Communication technology for paralysis has come a long way —from Stephen Hawking’s letter-by-letter selection to the possibility of decoding unspoken thoughts— and with careful attention to both capability and ethics, it has the potential to go even further.

References

- Wijesekera, L. C., & Nigel Leigh, P. (2009). Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Orphanet Journal of Rare Diseases, 4(1), 3. https://doi.org/10.1186/1750-1172-4-3

- Campbell, P. K., Jones, K. E., Huber, R. J., Horch, K. W., & Normann, R. A. (1991). A silicon-based, three-dimensional neural interface: Manufacturing processes for an intracortical electrode array. IEEE Transactions on Bio-Medical Engineering, 38(8), 758–768. https://doi.org/10.1109/10.83588

- Fernández, E., Greger, B., House, P. A., Aranda, I., Botella, C., Albisua, J., Soto-Sánchez, C., Alfaro, A., & Normann, R. A. (2014). Acute human brain responses to intracortical microelectrode arrays: Challenges and future prospects. Frontiers in Neuroengineering, 7. https://doi.org/10.3389/fneng.2014.00024

- Maynard, E. M., Nordhausen, C. T., & Normann, R. A. (1997). The Utah Intracortical Electrode Array: A recording structure for potential brain-computer interfaces. Electroencephalography and Clinical Neurophysiology, 102(3), 228–239. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0013-4694(96)95176-0

- Simonyan, K., & Horwitz, B. (2011). Laryngeal Motor Cortex and Control of Speech in Humans. The Neuroscientist : A Review Journal Bringing Neurobiology, Neurology and Psychiatry, 17(2), 197–208. https://doi.org/10.1177/1073858410386727

- Brown, S., Laird, A. R., Pfordresher, P. Q., Thelen, S. M., Turkeltaub, P., & Liotti, M. (2009). The somatotopy of speech: Phonation and articulation in the human motor cortex. Brain and Cognition, 70(1), 31–41. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bandc.2008.12.006

- Card, N. S., Wairagkar, M., Iacobacci, C., Hou, X., Singer-Clark, T., Willett, F. R., Kunz, E. M., Fan, C., Nia, M. V., Deo, D. R., Srinivasan, A., Choi, E. Y., Glasser, M. F., Hochberg, L. R., Henderson, J. M., Shahlaie, K., Stavisky, S. D., & Brandman, D. M. (2024). An Accurate and Rapidly Calibrating Speech Neuroprosthesis. New England Journal of Medicine, 391(7), 609–618. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa2314132

- Kunz, E. M., Abramovich Krasa, B., Kamdar, F., Avansino, D. T., Hahn, N., Yoon, S., Singh, A., Nason-Tomaszewski, S. R., Card, N. S., Jude, J. J., Jacques, B. G., Bechefsky, P. H., Iacobacci, C., Hochberg, L. R., Rubin, D. B., Williams, Z. M., Brandman, D. M., Stavisky, S. D., AuYong, N., … Willett, F. R. (2025). Inner speech in motor cortex and implications for speech neuroprostheses. Cell, 188(17), 4658-4673.e17. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cell.2025.06.015

- Hendriks, S., Grady, C., Ramos, K. M., Chiong, W., Fins, J. J., Ford, P., Goering, S., Greely, H. T., Hutchison, K., Kelly, M. L., Kim, S. Y. H., Klein, E., Lisanby, S. H., Mayberg, H., Maslen, H., Miller, F. G., Rommelfanger, K., Sheth, S. A., & Wexler, A. (2019). Ethical Challenges of Risk, Informed Consent, and Posttrial Responsibilities in Human Research With Neural Devices: A Review. JAMA Neurology, 76(12), 1506–1514. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamaneurol.2019.3523

Cover photo by Volodymyr Hryshchenko from UnSplash

Video 1: IntelFreePress on YouTube

Figures 1-2: Made in Adobe Illustrator and based on the results in Kunz et al., 2025

Video 2: Video S1 from Kunz et al., 2025 shared under the Creative Commons License

Leave a comment