February 3rd, 2026

Written by: Carris Borland

For neurons to be able to talk to each other, materials must be transported from one end to another along the length in the middle, called the axon. The axon acts like an electric cable connecting the two ends. Some axons can be quite long– stretching as far as the base of your spine to the very tip of your big toe! So, how do neurons with long axons get their supplies delivered on time, all the time? They use a family of proteins called kinesin motors (see video 1) to take cargo from one end of the neuron to the other. One kind of kinesin, also simply called ‘motors’, specialized for this timely, long-distance transport is called KIF1A. Let’s explore the unique properties that make this motor just right for the job.

What is KIF1A?

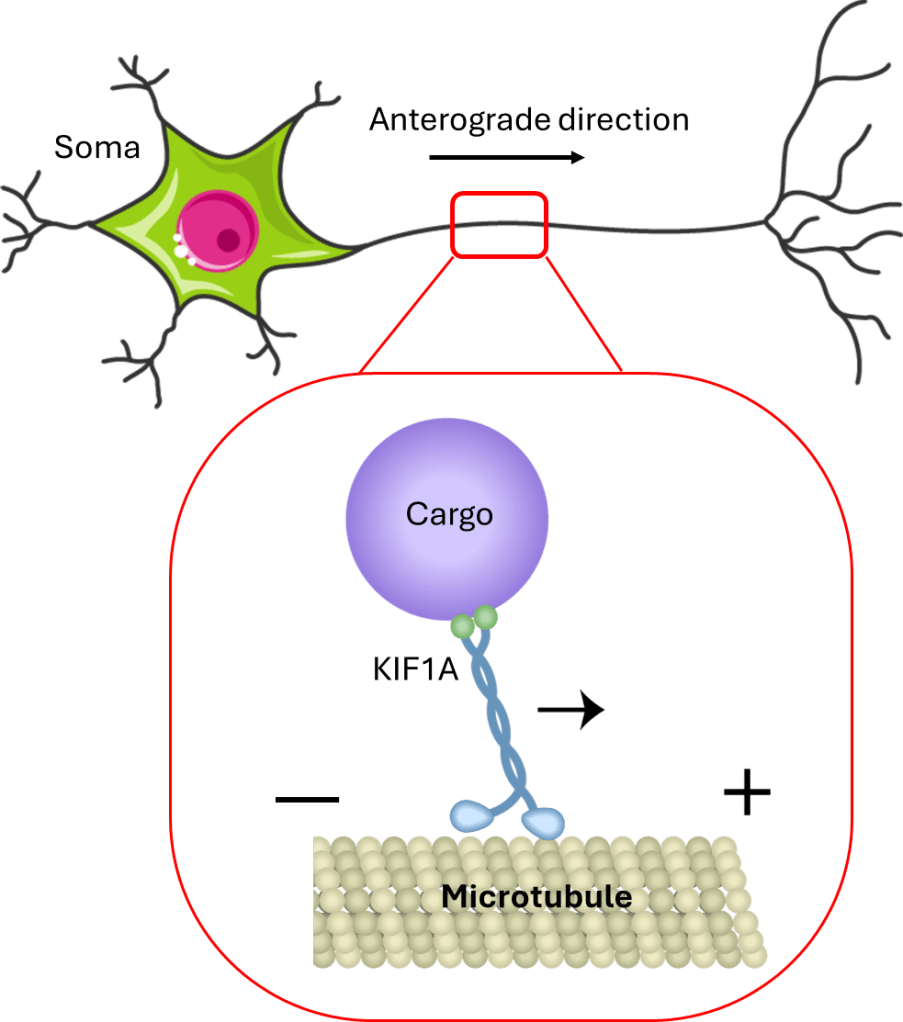

KIF1A is a kinesin motor protein that “walks” along the axon’s roadway, which is made of a material called microtubules, to deliver materials. KIF1A moves cargo down the length of neurons, but interestingly it only moves it one direction! It moves material from the body of the neuron (the soma) to the far end of the axon – which is called anterograde transport (Figure 1). KIF1A is mostly known for transporting supplies that are important for neuron-to-neuron communication, but recent work suggests that KIF1A also transports supplies that are important for a number of other vital processes1,2,3.

How is KIF1A structured?

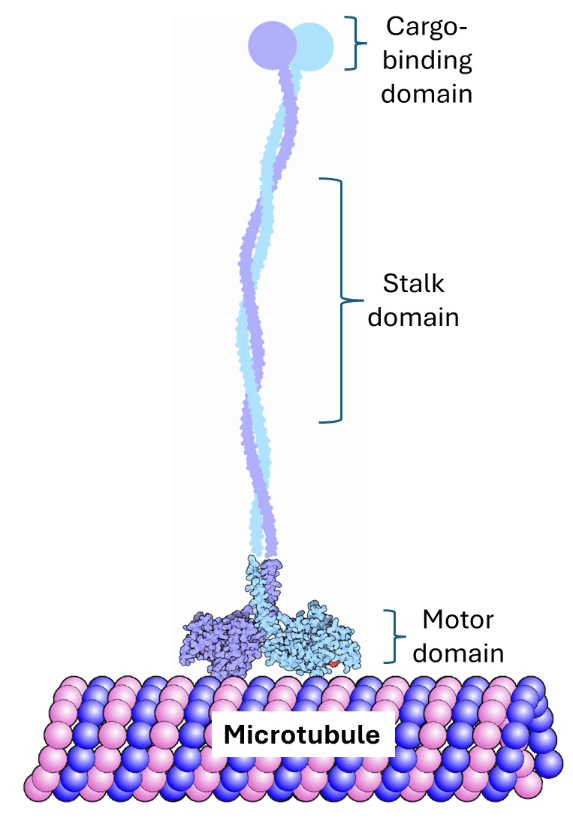

The KIF1A protein is composed of three parts (called domains) that equip it to transport cargo along the axon: the cargo-binding domain, the stalk domain and the motor domain (Figure 2). The cargo-binding domain identifies the cargo that needs to be transported and binds to it– basically picking it up ready to transport. The motor domain is the part that interacts with the microtubule. Finally, the stalk domain is a long stretch of protein between the motor domain and the cargo-binding domain that connects the two components (Figure 2).

How does KIF1A function?

With the KIF1A now assembled and the cargo loaded, how does it start moving to its destination? KIF1A moves along the microtubule similar to the way that we walk. Just like we alternate our two feet to walk forward, two pieces of the motor domain alternate attaching to the microtubule and pull the rest of the KIF1A along behind it. But this process isn’t a walk in the park– it takes effort and energy! KIF1A uses ATP, a common biological ‘fuel’, to power this process. The motor domain is specially designed to turn ATP into the energy needed for the KIF1A to ‘walk’ to the far end of the neuron (see Video 1)!

Why is KIF1A special?

Now we know what KIF1A looks like and how it moves, but what makes it perfect for long-distance travel? First, KIF1A is fast. It moves faster than other kinesin family members. Next, it can travel over long distances without falling off the microtubule. KIF1A takes long, continuous steps along microtubules, and can travel a longer distance than other kinesins. Lastly, it can handle roadblocks. The motor domains are specially equipped with the tools they need to reattach to the microtubule in cases where they fall off, enabling KIF1A to efficiently make it to the finish line4. All these properties make KIF1A important motors for long-distance transport.

What happens when this marathon runner struggles to run?

When KIF1A is unable to do its job properly, this results in a disease called KIF1A-Associated neurological disorder (KAND)5. People with this disease show a myriad of symptoms caused by KIF1A’s inability to function right. For example, people with KAND often suffer from vision problems. Vision works fast and relies on long axons from the eyes all the way to the back of the brain where visual information is processed. If KIF1A can’t travel along the axon, then the information we pick up with our eyes can’t reach the back of our brain fast enough. People with KAND also suffer from muscle weakness. We have neurons that connect to our muscles to tell them to move. If KIF1A can’t take cargo down those axons, then the muscles won’t receive enough messages to tell them to move. It’s amazing how one tiny kinesin is equipped with the tools to ultimately keep our neurons happy, and how devastating symptoms can result when KIF1A can’t function. Even when we’re at rest KIF1A is hard at work, certainly earning its name of the neuron’s “marathon runner”!

References

1. Yonekawa, Y., Harada, A., Okada, Y., Funakoshi, T., Kanai, Y., Takei, Y., Terada, S., Noda, T., & Hirokawa, N. (1998). Defect in synaptic vesicle precursor transport and neuronal cell death in KIF1A motor protein-deficient mice. The Journal of cell biology, 141(2), 431–441. https://doi.org/10.1083/jcb.141.2.431

2. Stavoe, A. K., Kargbo-Hill, S. E., Hall, D. H., & Colón-Ramos, D. A. (2016). KIF1A/UNC-104 Transports ATG-9 to Regulate Neurodevelopment and Autophagy at Synapses. Developmental cell, 38(2), 171–185. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.devcel.2016.06.012

3. Tanaka, Y., Niwa, S., Dong, M., Farkhondeh, A., Wang, L., Zhou, R., & Hirokawa, N. (2016). The Molecular Motor KIF1A Transports the TrkA Neurotrophin Receptor and Is Essential for Sensory Neuron Survival and Function. Neuron, 90(6), 1215–1229. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuron.2016.05.002

4. Pyrpassopoulos, S., Gicking, A. M., Zaniewski, T. M., Hancock, W. O., & Ostap, E. M. (2023). KIF1A is kinetically tuned to be a superengaging motor under hindering loads. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 120(2), e2216903120. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.2216903120

5. Chiba, K., Kita, T., Anazawa, Y., & Niwa, S. (2023). Insight into the regulation of axonal transport from the study of KIF1A-associated neurological disorder. Journal of cell science, 136(5), jcs260742. https://doi.org/10.1242/jcs.260742

Cover photo by Mahmur Marganti from pixaby

Figure 1 with images by Laboratoires Servier from Wikimedia Commons and by DataBase Center for Life Science (DBCLS) on Wikimedia Commons

Figure 2 adapted from image by David Goodsell from Wikimedia Commons under the Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Unported license

Linked video uploaded by Professor Chimp on Youtube.

Leave a comment