December 16th, 2025

Written by: Eve Gautreaux

Ancient Greek philosophers Hippocrates and Plato described a (nonexistent) condition in which the womb “wandered” around inside a woman*, causing emotional disturbances.1 Wandering womb later evolved into the even more popular diagnosis “hysteria” named after the Greek term for womb, hystera. Hysteria was used throughout the 18th and 19th centuries to refer to women who presented any behaviors considered to be unusual, undesirable, or otherwise medically mysterious.

Importantly, wandering womb and hysteria were influenced by the sexist belief that women were inferior to men, describing women as having a naturally “weaker nervous constitution” and “emotional instability” which makes them irrational.2 These labels were used to justify discrimination against women, such as arguing that women should not have a job or the right to vote.

Nearly a century ago, scientists discovered chemicals in the body that are present at different levels in men and women.3 These chemicals are sex hormones which play important roles in puberty and reproduction. Along with this discovery came the rebranding of wandering womb into “premenstrual tension”, a condition occurring before menstruation in women which was similarly characterized by mental and emotional symptoms such as “being slowed down … and proneness to quarrel”4 (modern translation: tiredness and irritability) that were now claimed to be due to sex hormones.5 Shortly after, this term was replaced with “premenstrual syndrome” or as many of us know it: PMS.6

How much of our idea about PMS today is an artifact of sexist origins like hysteria versus actual biology?

What are premenstrual disorders?

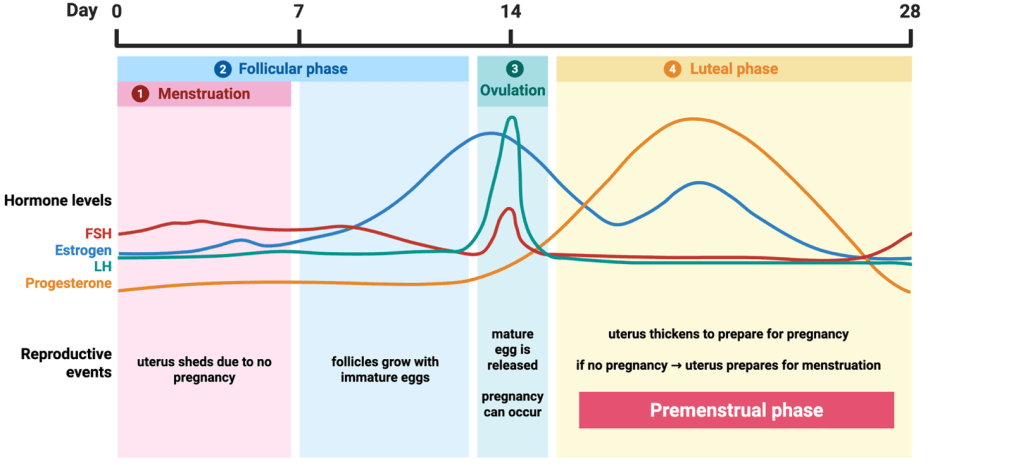

Many hormones are released in a cycle. Although men and women release the same hormones, the quantity and time course of release differ between sexes.3 While the sex hormone cycle in men is 24 hours, women’s sex hormone cycle is about 28 days! The female cycle is longer because, unlike in men, it is linked to reproduction. The fluctuations of hormone levels cue four phases of events in the uterus and ovaries (Figure 1).

- Week one of the cycle is menstruation (AKA the “period”) where the uterus sheds its lining due to no pregnancy occurring.

- Menstruation overlaps with the follicular phase, which spans the first two weeks of the cycle when follicles (sacs containing immature eggs) grow.

- Around days 13-15, the eggs are mature and an egg is released from a follicle, a process called ovulation. Now is when the egg can be fertilized and pregnancy can occur.

- The last two weeks or so are the luteal phase which begins with the uterus thickening its lining to prepare for potential pregnancy. If pregnancy doesn’t occur, the uterus prepares for shedding (AKA menstruation) which means it is also the premenstrual phase.

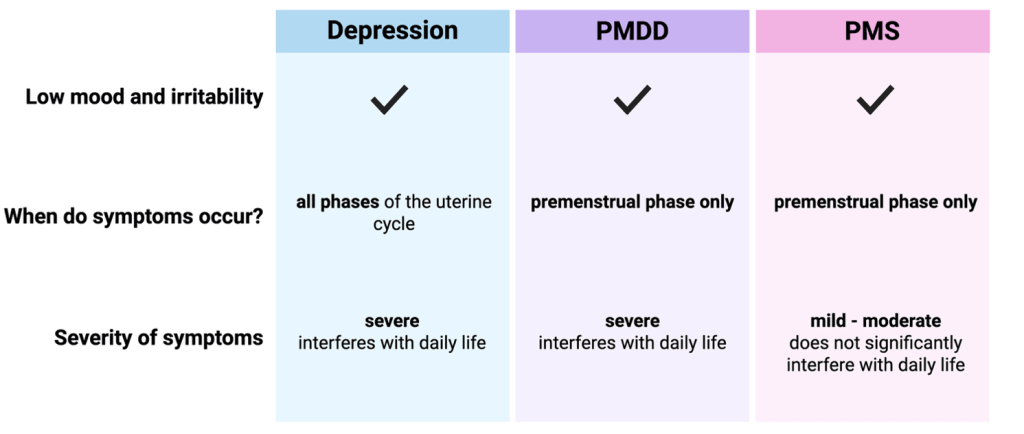

PMS is defined by symptoms that appear during the 1-2 weeks before menstruation AKA the premenstrual phase. These symptoms include psychological symptoms, such as irritability and low mood, as well physical symptoms such as breast tenderness and headaches.

About 40 years ago, scientists began to describe a form of PMS known as Premenstrual Dysphoric Disorder (PMDD).7 The only difference between PMS and PMDD is that PMDD is characterized by more severe symptoms6 (Figure 2). For example, while a person experiencing PMS may feel sad, a person experiencing PMDD is depressed and may even have suicidal thoughts. For this reason, PMDD is officially listed as a mental health disorder in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual (DSM), a guide used by mental health physicians.8 However, unlike depression, symptoms only occur during the 1-2 weeks before menstruation and improve during the other weeks of the cycle.

The differences in symptoms between PMS, PMDD, and other mental health disorders has been clearly described, but what leads to these differences?

What is the biology of premenstrual disorders?

Interestingly, women with PMS and PMDD show no differences in hormone levels or the pattern of fluctuations compared to women without symptoms.6 However, studies suggest that those with PMS and PMDD differ from women without symptoms in the way that their body responds to the hormone fluctuation that triggers the luteal (premenstrual) phase.

When your body encounters a threat such as an infection, it calls on the immune system to protect it. The immune system responds by sending special cells that release proteins called cytokines to fight the threat, resulting in inflammation. However, too much inflammation can damage healthy cells and disrupt functions in your body.9

Studies have found that women with PMS and PMDD have higher levels of inflammatory cytokines during the premenstrual phase, which suggests that their bodies are treating a normal fluctuation in sex hormones like an infection6.

The immune system can mistake healthy tissue in your body for invaders like bacteria or viruses in which the damaging inflammation to your healthy tissue causes disease known as an autoimmune disorder. Although premenstrual disorders aren’t technically classified as autoimmune disorders (yet), they share the same key process: an abnormal immune response to healthy body tissue (or chemicals) increases inflammation, causing negative symptoms. Another common trait is that a whopping 80% of people with autoimmune disorders are women!10

What would cause a person’s body to essentially respond to itself like an invader? A likely culprit is chronic stress.

What’s behind the inflammation of premenstrual disorders?

Women with PMS and PMDD report significantly higher stress levels than women without symptoms.6 Not only is stress higher in women with PMS and PMDD, but some studies have found a correlation between premenstrual disorders and trauma early in life.11 People who experience traumatic stress early in life are twice as likely to develop certain inflammatory diseases and autoimmune disorders.12 This points toward stress as a likely cause of inflammation in women with premenstrual symptoms.

Whenever you experience stress, your body releases a hormone called cortisol which, in the short-term, helps you cope with stress by boosting the immune system and keeping inflammation in check. However, long periods of increased cortisol cause your immune system to stop listening to cortisol, causing excess inflammation.9

Women with PMDD but no history of depression have higher cortisol than women without PMDD. However, women with PMDD and a history of depression have lower cortisol than both groups.13 This difference may be explained by some studies showing that especially long periods of stress or especially traumatic stress eventually leads to less cortisol due to the body trying to adapt and prevent further damage.13 However, mixed findings of cortisol levels could also be due to inconsistent methods of collecting cortisol samples. More research is needed to fully understand the complex effects of stress on cortisol in women with PMS and PMDD.

Taken together, women with premenstrual symptoms have higher stress which might explain their excess inflammation. But how is this inflammation linked to psychological symptoms such as low mood?

How can inflammation lead to psychological symptoms?

Serotonin is a chemical released in the brain that is involved in many functions including sleep, appetite, and mood. Low levels of serotonin are linked to depression. The building block of serotonin has two paths it can take: make serotonin or get broken down. Inflammatory cytokines increase the odds of the serotonin building block getting broken down into smaller chemicals. These smaller chemicals are found to be higher in women with premenstrual symptoms, indicating that serotonin is being broken down.6 This suggests that, similar to depression, women with PMS or PMDD have less of the mood-boosting serotonin.

Several research studies point to a few key biological pieces of the premenstrual symptom puzzle. Does this mean the case is closed on stigma and bias playing a role in the understanding of premenstrual disorders today?

Controversy of premenstrual disorders

Many experts argue that premenstrual disorders, specifically premenstrual “syndrome” (PMS), pathologize women’s emotions and responses.14 In other words, calling something a “disorder” or “syndrome” implies that it is abnormal. These experts argue that premenstrual symptoms are a normal bodily response whether it be experiencing abdominal pain, or feeling sad, irritated or tired while your body is low on important hormones and expending extra energy15 to prepare for a week of bleeding 24/7. Notably, the role of physical symptoms is often ignored in research, despite pain being the most common PMS symptom.2

What about PMDD though? Is it just “normal”? Unlike PMS, women diagnosed with PMDD experience especially debilitating physical, emotional, or mental symptoms. These severe symptoms only affect around 1-3% of women,16 making it safe to say it is not “the norm”. Based on the current evidence, PMDD appears to be a kind of autoimmune disorder. It is important to ensure these experiences are not dismissed or minimized but instead treated the same as any other disease such as diabetes or depression which affect men too.

We invest in researching diseases such as diabetes and depression and make efforts to help people experiencing them. Let’s do the same for women and those with premenstrual disorders, being careful to not let the history of hysteria—which used (false) science to discriminate against women—repeat itself.

*Note: This article uses ‘women’ to describe people who experience or have experienced menstrual cycles while recognizing that not all people who identify as women menstruate, and not all people who menstruate identify as women.

References

1. Tasca, C., Rapetti, M., Carta, M. G. & Fadda, B. Women and hysteria in the history of mental health. Clin. Pract. Epidemiol. Ment. Health 8, 110–119 (2012).

2. King, S. Premenstrual Syndrome (PMS) and the myth of the irrational female. in The Palgrave Handbook of Critical Menstruation Studies 287–302 (Springer Singapore, Singapore, 2020).

3. Tata, J. R. One hundred years of hormones: A new name sparked multidisciplinary research in endocrinology, which shed light on chemical communication in multicellular organisms. EMBO Rep. 6, 490–496 (2005).

4. Richardson, J. T. The premenstrual syndrome: a brief history. Soc. Sci. Med. 41, 761–767 (1995).

5. Frank, R. T. The hormonal causes of premenstrual tension. Arch. Neurol. Psychiatry 26, 1053 (1931).

6. Cheng, M. et al. The role of the neuroinflammation and stressors in premenstrual syndrome/premenstrual dysphoric disorder: a review. Front. Endocrinol. (Lausanne) 16, 1561848 (2025).

7. Cooper, A. M. & Michels, R. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 3rd ed., revised (DSM-III-R). Am. J. Psychiatry 145, 1300–1301 (1988).

8. American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. DSM Library https://psychiatryonline.org/doi/epub/10.1176/appi.books.9780890425787.

9. Alotiby, A. Immunology of stress: A review article. J. Clin. Med. 13, 6394 (2024).

10. Lovell, C. D. & Anguera, M. C. More X’s, more problems: how contributions from the X chromosomes enhance female predisposition for autoimmunity. Curr. Opin. Immunol. 93, 102543 (2025).

11. Standeven, L. R. et al. The link between childhood traumatic events and the continuum of premenstrual disorders. Front. Psychiatry 15, 1443352 (2024).

12. Dube, S. R. et al. Cumulative childhood stress and autoimmune diseases in adults. Psychosom. Med. 71, 243–250 (2009).

13. Klatzkin, R. R., Lindgren, M. E., Forneris, C. A. & Girdler, S. S. Histories of major depression and premenstrual dysphoric disorder: Evidence for phenotypic differences. Biol. Psychol. 84, 235–247 (2010).

14. Islas-Preciado, D., Ramos-Lira, L. & Estrada-Camarena, E. Unveiling the burden of premenstrual dysphoric disorder: a narrative review to call for gender perspective and intersectional approaches. Front. Psychiatry 15, 1458114 (2024).

15. Davidsen, L., Vistisen, B. & Astrup, A. Impact of the menstrual cycle on determinants of energy balance: a putative role in weight loss attempts. Int. J. Obes. (Lond) 31, 1777–1785 (2007).

16. Reilly, T. J. et al. The prevalence of premenstrual dysphoric disorder: Systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Affect. Disord. 349, 534–540 (2024).

Cover photo by Auguste Toulmouche from Wikimedia Commons.

Figures 1 and 2 created by Eve Gautreaux in https://BioRender.com.

Just wanted to say thank you!!

As someone with PMDD, it is incredibly frustrating for most people to be unaware or outright dismissive of a condition that left me bedbound for two weeks every month.

I have an interest in medical history, and it angers me to no end when articles talking about hysteria neglect to mention PMDD, or worse – describe them both as “made up diseases to pathologies women”. As someone with the disorder, a decade before I’d even heard the word I would know I needed to ask my mum to restock my pads when I started feeling suicidal.

It’s also frustrating how little research there is, and said research almost exclusively treats it as a psychological condition when as you point out, there is CLEAR evidence of immune involvement. I found a paper from *1946* (back when it was still called PMT) that suggested it was an autoimmune condition, back when the idea that you could be allergic to your own body was still a fringe idea! It is heartbreaking that the biggest conversation around PMDD in 2025 is still just whether it exists at all.

LikeLike