December 9th, 2025

Written by: Hayley Lenhard

Have you suffered from a case of the common cold recently? I know I have. It’s that time of year after all. The good news about the pesky common cold is that it typically goes away on its own without the need for medical intervention beyond perhaps some over-the-counter cold symptom relief. So how does your body fight off a cold? This article will focus on one answer: T cells, a type of immune cell. We’ll explore how these cells work to help protect your brain and body from germs, as well as what can happen if these usually helpful cells betray us.

T cells are one of the unseen heroes at least partially responsible for your recovery from the common cold. T cells work as part of your immune system, which protects your body from foreign invaders; think of it as your body’s personal army! T cells act like soldiers within this army that fight off the germs that cause those nasty cold symptoms. T cells can help your body fight off all kinds of diseases, from your run-of-the-mill cold or flu to more chronic or serious conditions such as tuberculosis, HIV, or cancer, though it’s important to note that these more serious conditions usually require backup from medical intervention.1

T cells as friends: How your T cells fight off germs

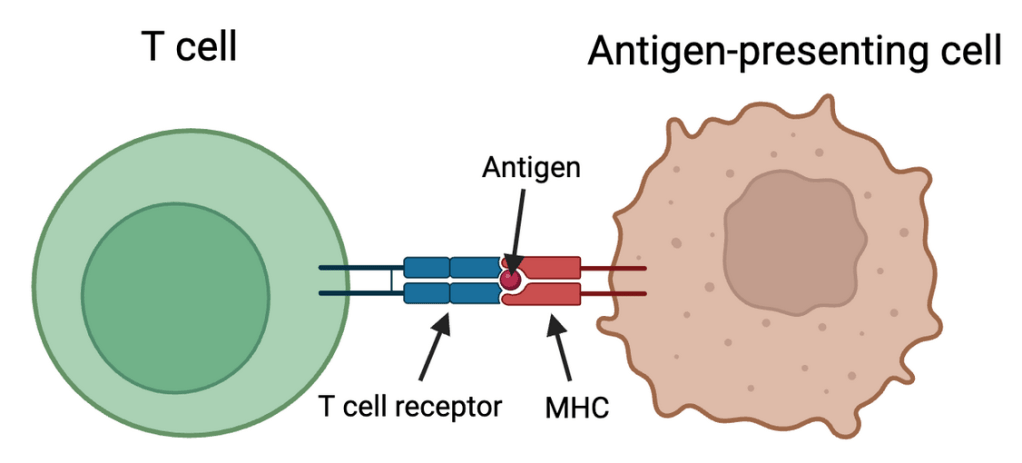

So how do these helpful cells work? Well, before a T cell can destroy infected or cancerous cells, it must first be activated. Similar to how you might feel incapable of functioning before your morning cup of coffee, T cells are unable to perform their crucial immune functions without first being activated. But instead of an iced latte or an energy drink, T cells are activated by foreign proteins, known as antigens, that are produced by tumor cells or cells that are infected with a bacteria or virus. These foreign antigens are carried to T cells by a helpful type of cell, aptly named as antigen-presenting cells. But there’s a catch. T cells cannot be activated by these antigens unless another protein, called the major histocompatibility complex (MHC), is also present. When the antigen-presenting cell uses MHC to present the antigen to special receiving ports on the T cell, called receptors, the T cells are activated and can jump into action to defend your body against the threat (Figure 1). If you think of T cells as baseball players, the T-cell receptors are like baseball gloves that the T cells use to catch baseballs (antigens) that are hit to them by the batter (the antigen-presenting cell) which uses MHC like a baseball bat.

Once T cells have been activated by an antigen, they can do all sorts of cool things! First, T cells will start to multiply: rapidly increasing the number of players that are available to help fight off the opposing team. In this case, the formidable opponent is infection. Much like the players on your favorite baseball team, T cells can play different roles in the fight against infection. Helper T cells are the coaches that organize the attack by releasing signals that alert other T cells to the threat.2 Once they “catch” the signal from the helper T cells, the aptly named killer T cells work on the defense, doing the dirty work of actually destroying the infected or cancerous cells before they can take over.2 Regulatory T cells are the umpires that work to keep the immune response in check to prevent it from causing chronic or severe inflammation.3

T cells in the brain

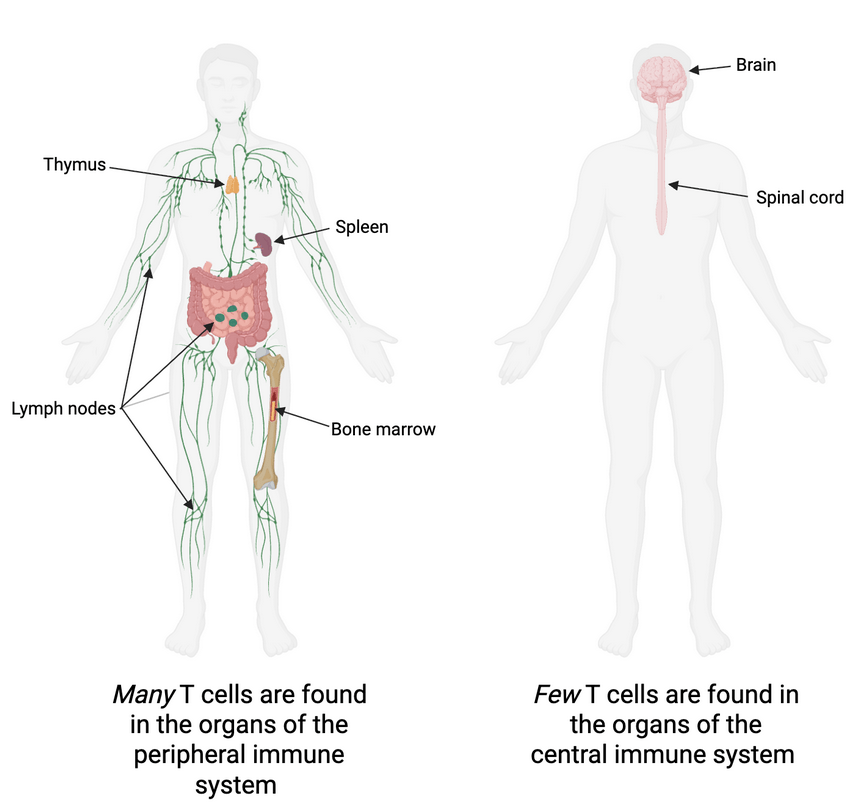

T cells are primarily located outside the brain and spinal cord in the peripheral immune system (Figure 2). In the peripheral immune system, T cells originate in the bone marrow and then travel to a gland called the thymus where they mature. Think of the thymus as a school for T cells. Once the T cells are fully mature, they graduate from the thymus and can start circulating through the blood to organs such as the spleen or lymph nodes where they wait until they are needed to fight off an infection.5 In some cases, however, T cells can venture from their home in the peripheral immune system and travel to the brain or spinal cord, entering the central immune system. T cell infiltration into the brain can be triggered by infection or injury; under healthy conditions, these cells are rarely found in brain tissue.6

In the brain, T cells sometimes function similarly to how they do in the peripheral immune system. When a virus attacks the brain, T cells can move in, fight against the initial infection, and then remain in the brain even after the virus has been defeated, helping to prevent future infection by the same virus.7,8

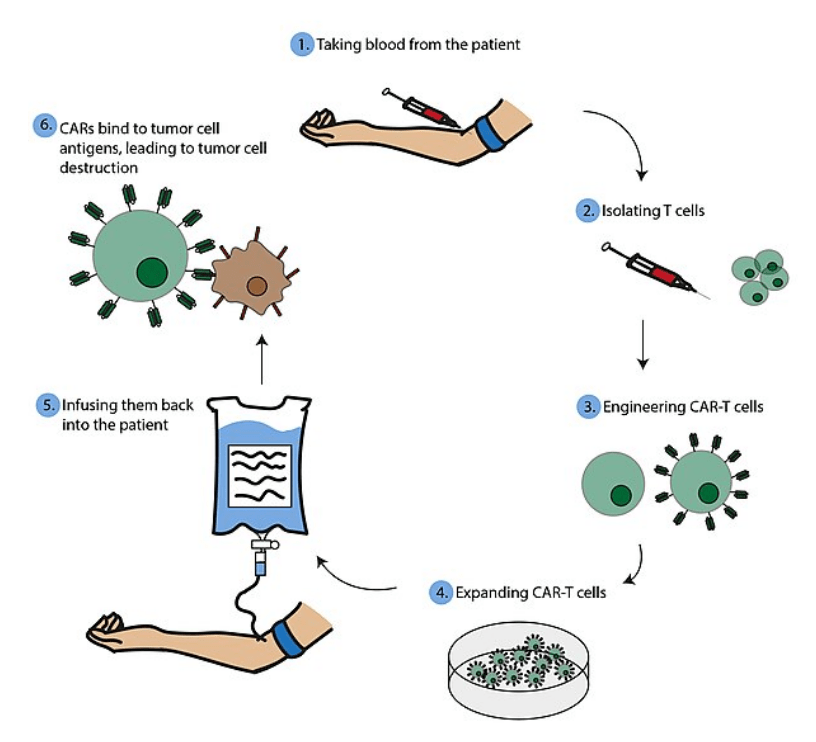

Doctors and scientists have also been able to harness and enhance the power of T cells to develop treatments for an aggressive form of brain cancer called glioblastoma. Scientists have found ways to engineer T cells that can hone in on brain tumor cells and target them specifically for destruction (Figure 3). These special T cells are referred to as CAR-T cells (chimeric antigen receptor T cells). To make these cells, normal T cells are collected from a patient’s blood and a special receptor is added to them that is made to specifically target an antigen that is known to be produced by the brain tumor.9,10 Kind of like how dogs can be trained to track certain scents, these CAR-T cells can be created to track certain antigens. Finally, the CAR-T cells are delivered back to the patient, typically through intravenous infusion. They should then be able to travel to the brain and recognize tumor cell antigens more efficiently than the patient’s normal T cells would.

CAR-T therapy has proven to be very effective for certain cancers such as leukemias or lymphomas, with some patients even being able to reach complete remission.11,12 Glioblastoma has proven to be more stubborn. Though CAR-T therapy shows promise for treating glioblastoma, results from clinical trials have varied in terms of its ability to slow disease progression in patients.13,14,15 Scientists are actively working to improve the effectiveness of CAR-T therapy for this aggressive form of brain cancer and clinical trials are ongoing.

But be warned! T cells aren’t always as nice as they seem….

T cells as foes: When your T cells turn against you

While T cells are crucial for keeping you healthy, you certainly don’t want to end up on their bad side. Autoimmune diseases can occur when the immune system runs wild and starts to mistakenly kill perfectly healthy cells. Though T cells are good at attacking infected cells or tumors, sometimes they can be a little too good at their job. If this happens, an autoimmune disease can develop, where overeager T cells start to destroy healthy cells. One such autoimmune disease, multiple sclerosis, affects the brain. In this disease, T cells attack and destroy the protective covering around neurons, a type of brain cell, causing them to die.16 Autoimmune encephalitis is another disease in which T cells attack healthy brain cells,17 resulting in brain swelling that can lead to symptoms such as memory loss, hallucinations, and seizures.18 Though scientists still aren’t sure what exactly triggers your immune cells to turn against you, some factors that are thought to increase the risk of developing an autoimmune disease are exposure to certain chemicals or environmental hazards, smoking, or having a family member with an autoimmune disease.19

T cells have also been found to play a detrimental role in neurodegenerative diseases, conditions that result in the gradual death of neurons and result in symptoms like memory loss, movement deficits, and behavioral changes. In Alzheimer’s disease, T cells that infiltrate the brain cause inflammation that can increase neuron death.20 Similarly, in Parkinson’s disease and Lewy body dementia, infiltrating T cells have been found to produce proteins that are damaging to neurons.21,22 In these cases, T cells appear to actually hurt neurons instead of protecting them.

Conclusion

T cells normally function as fierce protectors, working to defend your body and brain from evil invaders such as infection or cancer. This winter, your T cells will work hard to keep you healthy during cold and flu season. CAR-T cell therapy can harness the natural powers of T cells to enhance tumor cell killing in cancers like leukemia or glioblastoma. But occasionally, for reasons that aren’t exactly clear yet, these typically friendly cells can get a little too excited and start attacking perfectly healthy cells, leading to the development of autoimmune diseases such as multiple sclerosis or autoimmune encephalitis. They can also exacerbate neuron death in neurodegenerative diseases like Alzheimer’s, Parkinson’s, or Lewy body dementia.

So T cells: friend or foe? It turns out the answer is both.

References

- Sun, L., Su, Y., Jiao, A., Wang, X. & Zhang, B. T cells in health and disease. Sig Transduct Target Ther 8, 235 (2023).

- T cells. Cleveland Clinic. https://my.clevelandclinic.org/health/body/24630-t-cells.

- Cytotoxic T cells. Cleveland Clinic. https://my.clevelandclinic.org/health/body/23547-cytotoxic-t-cells.

- Vignali, D.A.A., Collison, L.W. & Workman, C.J. How Regulatory T Cells Work. Nature Reviews Immunology 8, 523-532 (2008).

- Thymus. Cleveland Clinic. https://my.clevelandclinic.org/health/body/23016-thymus.

- Rua, R. & McGavern, D.B. Advances in Meningeal Immunity. Trends Mol Med 24, 542-559 (2018).

- Brizić, I., Šušak, B., Arapović, M., Huszthy, P.C., Hiršl, L., Kveštak, D., Juranić Lisnić, V., Golemac, M., Pernjak Pugel, E., Tomac, J., Oxenius, A., Britt, W.J., Arapović, J., Krmpotić, A. & Jonjić, S. Brain-resident memory CD8+ T cells induced by congenital CMV infection prevent brain pathology and virus reactivation. Eur J Immunol 48, 950-964 (2018).

- Mockus, T.E., Netherby-Winslow, C.S., Atkins, H.M., Lauver, M.D., Jin, G., Ren, H.M. & Lukacher, A.E. CD8 T Cells and STAT1 Signaling Are Essential Codeterminants in Protection from Polyomavirus Encephalopathy. Journal of Virology 94, e02038-19 (2020).

- Gargett, T., Ebert, L.M., Truong, N.T.H., Kollis, P.M., Sedivakova, K., Yu, W., Yeo, E.C.F., Wittwer, N.L., Gliddon, B.L., Tea, M.N., Ormsby, R., Poonnoose, S., Nowicki, J., Vittorio, O., Ziegler, D.S., Pitson, S.M. & Brown, M.P. GD2-targeting CAR-T cells enhanced by transgenic IL-15 expression are an effective and clinically feasible therapy for glioblastoma. J Immunother Cancer 10, 9 (2022).

- Choe, J.H., Watchmaker, P.B., Simic, M.S., Gilbert, R.D., Li, A.W., Krasnow, N.A., Downey, K.M., Yu, W., Carrera, D.A., Celli, A., Cho, J., Briones, J.D., Duecker, J.M., Goretsky, Y.E., Dannenfelser, R., Cardarelli, L., Troyanskaya, O., Sidhu, S.S., Roybal, K.T., Okada, H. & Lim, W.A. SynNotch-CAR T cells overcome challenges of specificity, heterogeneity, and persistence in treating glioblastoma. Sci Transl Med 13, 591 (2021).

- Porter, D.L., Hwang, W., Frey, N.V., Lacey, S.F., Shaw, P.A., Loren, A.W., Bagg, A., Marcucci, K.T., Shen, A., Gonzalez, V., Ambrose, D., Grupp, S.A., Chew, A., Zheng, Z., Milone, M.C., Levine, B.L., Melenhorst, J.J. & June, C.H. Chimeric antigen receptor T cells persist and induce sustained remissions in relapsed refractory chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Science Translational Medicine 7, 303ra139 (2015).

- Kochenderfer, J.N., Dudley, M.E., Kassim, S.H., Somerville, R.P., Carpenter, R.O., Stetler-Stevenson, M., Yang, J.C., Phan, G.Q., Hughes, M.S., Sherry, R.M., Raffeld, M., Feldman, S., Lu, L., Li, Y.F., Ngo, L.T., Goy, A., Feldman, T., Spaner, D.E., Wang, M.L., Chen, C.C., Kranick, S.M., Nath, A., Nathan, D.A., Morton, K.E., Toomey, M.A. & Rosenberg, S.A. Chemotherapy-refractory diffuse large B-cell lymphoma and indolent B-cell malignancies can be effectively treated with autologous T cells expressing an anti-CD19 chimeric antigen receptor. J Clin Oncol 33, 540-549 (2015).

- Liu, Z., Zhou, J., Yang, X., Liu, Y., Zou, C., Lv, W., Chen, C., Cheng, K..K., Chen, T., Chang, L.J., Wu, D. & Mao, J. Safety and antitumor activity of GD2-Specific 4SCAR-T cells in patients with glioblastoma. Mol Cancer 22, 3 (2023).

- Begley, S.L., O’Rourke, D.M. & Binder, Z.A. CAR T cell therapy for glioblastoma: A review of the first decade of clinical trials. Molecular Therapy 33, 2454-2461 (2025).

- Agosti, E., Garaba, A., Antonietti, S., Ius, T., Fontanella, M.M., Zeppieri, M. & Panciani, P.P. CAR-T Cells Therapy in Glioblastoma: A Systematic Review on Molecular Targets and Treatment Strategies. Int J Mol Sci 25, 13 (2024).

- Kaskow, B.J. & Baecher-Allan, C. Effector T Cells in Multiple Sclerosis. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Med 8, a029025 (2018).

- Chen, J., Qin, M., Xiang, X., Guo, X., Nie, L. & Mao, L. Lymphocytes in autoimmune encephalitis: Pathogenesis and therapeutic target. Neurobiology of Disease 200, 106632 (2024).

- Autoimmune Encephalitis. Mayo Clinic. https://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/autoimmune-encephalitis/symptoms-causes/syc-20576380.

- Autoimmune Diseases. Cleveland Clinic. https://my.clevelandclinic.org/health/diseases/21624-autoimmune-diseases.

- Jorfi, M., Park, J., Hall, C.K., Lin, C.J., Chen, M., von Maydell, D., Kruskop, J.M., Kang, B., Choi, Y., Prokopenko, D., Irimia, D., Kim, D.Y. & Tanzi, R.E. Infiltrating CD8+ T cells exacerbate Alzheimer’s disease pathology in a 3D human neuroimmune axis model. Nat Neurosci 26, 1489-1504 (2023).

- Williams, G.P., Schonhoff, A.M., Jurkuvenaite, A., Gallups, N.J., Standaert, D.G. & Harms, A.S. CD4 T cells mediate brain inflammation and neurodegeneration in a mouse model of Parkinson’s disease. Brain 144, 2047–2059 (2021).

- Gate, D., Tapp, E., Leventhal, O., Shahid, M., Nonninger, T.J., Yang, A.C., Strempfl, K., Unger, M.S., Fehlmann, T., Oh, H., Channappa, D., Henderson, V.W., Keller, A., Aigner, L., Galasko, D.R., Davis, M.M., Poston, K.L. & Wyss-Coray, T. CD4+ T cells contribute to neurodegeneration in Lewy body dementia. Science 374, 868-874 (2021).

Figures 1 and 2 created by Hayley Lenhard with Biorender

Figure 3 by Albrecht.L on Wikimedia Commons

Cover photo was generated on ChatGPT

Leave a comment