December 2nd, 2025

Written by: Anna Kasper

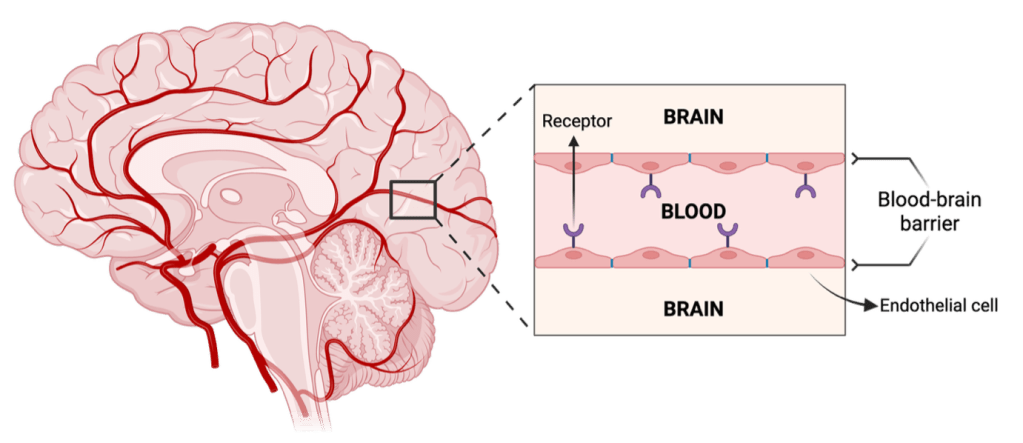

Picture your brain, made up of all its grooves, nooks, and crannies. Snaking through these nooks and crannies are channels of blood known as blood vessels (Figure 1). When blood flows through these channels, it carries important cargo that your brain needs, like oxygen. But it can also carry harmful cargo, like pathogens. To help keep the harmful cargo out, a physical wall known as the blood-brain barrier separates the brain from the blood (Figure 1). The brain needs this barrier, because it doesn’t have a built-in filtration system like other organs do (such as the kidney)1. Here, we use Greek mythology to help understand what the blood-brain barrier is as well as the different drug delivery approaches.

The Trojan War Inside the Brain

Often, when I think about the blood-brain barrier, I imagine the walls of Troy, the city where the mythical Trojan War took place. During this long, brutal war, the Greeks laid siege to Troy, which was nearly impenetrable – its impressive walls were stacked with stones and said to have been to keep enemies out. The only way the Greeks could pass this barrier was by tricking the Trojans – they pretended to retreat, leaving behind a massively majestic wooden horse as a “peace offering”. Ecstatic, the Trojans brought the horse inside their city, unaware that the Greeks hid inside. When night fell, the Greeks sprang out from inside the Trojan horse and ambushed Troy, winning the war.

Similarly to Troy’s walls, the blood-brain barrier is a formidable defense. It’s made of many components that help preserve and fortify its structure. One key component is endothelial cells2,3 (Figure 1), which make up the bulk of the barrier by fitting tightly together like stones in a wall. Endothelial cells line blood vessels and help control the flow of blood, nutrients, and other substances in and out of the brain2,3. Other components of the barrier include receptors which act like guard sentries located along endothelial cells (Figure 1). They closely guard passages across endothelial cells and determine what substances can cross into the brain and what substances must be kept out1,2. If they recognize the substance that approaches, they will allow the substance to pass, but if they don’t recognize the substance, they will refuse the substance entry into the brain. A healthy blood-brain barrier is successful at recognizing harmful versus helpful cargo and determining its flow into the brain.

In the context of brain disease, the blood-brain barrier’s greatest strength (its protective nature) can also be its downfall – it can deny entry for drugs that would be beneficial to treat the disease because it doesn’t recognize the drugs3. So, how can neuroscientists deliver effective treatments across the blood-brain barrier when the barrier sees these foreign substances as enemies? To solve this, researchers are working to develop a variety of Trojan horses – therapies that travel through the blood, trick the barrier, and act inside the brain.

How do Trojan Horses work in the brain?

To develop Trojan horses for the brain, neuroscientists generally aim to exploit the receptors in the blood-brain barrier and trick them into allowing drugs to enter the brain2,3. Like how the Greeks hid in the Trojan horse, researchers can “hide” drugs by attaching them to a substance that barrier receptors recognize. Different receptors will recognize different substances, so it’s important that when choosing a receptor to target, scientists must pick one where 1) the drug will stay attached to the substance until it crosses the barrier and 2) the receptor is easily fooled and does not see the attached drug.

A real-life application of Trojan Horse drug delivery in the brain: Hunter Syndrome

A current example of a disorder where scientists are testing the Trojan horse approach is Hunter syndrome. In Hunter syndrome, patients develop intellectual disabilities and skeletal problems due to missing an important component in the brain called iduronate 2-sulfatase4. Iduronate 2-sulfatase helps break down specific sugars in the brain – when iduronate 2-sulfatase is missing, these sugars will accumulate and become toxic to patients5,6. So to deliver iduronate 2-sulfatase to patients who need it, researchers tried to attach it to substances known as anti-transferrin antibodies, which are recognized by the transferrin receptor located within the barrier6,7. Excitingly, one clinical study in Brazil provided evidence that this seems to help patients with Hunter syndrome, as patients who took the drug had improved developmental functioning6.

Taking inspiration from viruses: natural masters of the Trojan horse approach

In developing other Trojan horse approaches to drug delivery across the brain, researchers have taken inspiration from a surprising source – viruses. Viruses are very small pathological agents that like to wreak havoc wherever they can go, including the brain. It’s one of the things that the blood-brain barrier tries to prevent from entering the brain, but some viruses have cleverly mastered Trojan horse approaches and can bypass the barrier anyway. Researchers have attempted to understand how and which viruses can bypass the barrier – here, I’ll briefly describe two types of viruses they’ve found: adeno-associated viruses and human immunodeficiency virus (HIV).

Like the Greeks hidden in the horse, adeno-associated viruses bypass the barrier by creating packages that they can hide in. These packages are recognized by receptors located along the barrier and perceived as harmless, allowing them to cross the blood-brain barrier and carry out harmful actions8 (Figure 2). However, scientists have figured out ways to re-purpose the packages by removing the viruses and replacing them with treatment drugs. On the other hand, HIV will bypass the barrier by using a slightly different Trojan horse – instead of making its own packages to present to barrier receptors, HIV will infect existing immune cells that circulate throughout the blood. They essentially “hitch a ride” in immune cells with the special ability to squeeze between the endothelial cells9,10,11 (Figure 2), much like how cats can contort themselves to slip through narrow gaps underneath fences. While researchers are still studying different ways to disable HIV and mimic this Trojan horse strategy, studying HIV has given researchers a broader understanding of how viruses infect cells12.

Conclusion

Overall, finding safe ways to bypass the blood-brain barrier to treat brain diseases remains a formidable challenge. But like the relentless Greeks, scientists continue to innovate and persevere in refining strategies. With ongoing research, scientists are building a deeper understanding of the mighty blood-brain barrier and how to defeat it.

References

1. McGaughey, K (2024). The brain’s gatekeeper: A closer look at the blood-brain barrier. PennNeuroKnow. [Accessed 12/1/25]

2. Katzourakis A, Tristem M, Pybus OG, Gifford RJ (2007) Discovery and analysis of the first endogenous lentivirus. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 104:6261–6265.

3. Laterra J, Keep R, Betz LA, Goldstein GW (1999) Blood—Brain Barrier. In: Basic Neurochemistry: Molecular, Cellular and Medical Aspects. 6th edition. Lippincott-Raven. Available at: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK28180/ [Accessed November 30, 2025].

4. Lippmann ES, Azarin SM, Kay JE, Nessler RA, Wilson HK, Al-Ahmad A, Palecek SP, Shusta EV (2012) Human Blood-Brain Barrier Endothelial Cells Derived from Pluripotent Stem Cells. Nat Biotechnol 30:783–791.

5. Demydchuk M, Hill CH, Zhou A, Bunkóczi G, Stein PE, Marchesan D, Deane JE, Read RJ (2017) Insights into Hunter syndrome from the structure of iduronate-2-sulfatase. Nat Commun 8:15786.

6. Osaki Y, Saito A, Kanemoto S, Kaneko M, Matsuhisa K, Asada R, Masaki T, Orii K, Fukao T, Tomatsu S, Imaizumi K (2018) Shutdown of ER-associated degradation pathway rescues functions of mutant iduronate 2-sulfatase linked to mucopolysaccharidosis type II. Cell Death Dis 9:808.

7. Giugliani R, Martins AM, So S, Yamamoto T, Yamaoka M, Ikeda T, Tanizawa K, Sonoda H, Schmidt M, Sato Y (2021) Iduronate-2-sulfatase fused with anti-hTfR antibody, pabinafusp alfa, for MPS-II: A phase 2 trial in Brazil. Molecular Therapy 29:2378–2386.

8. Okuyama T, Eto Y, Sakai N, Minami K, Yamamoto T, Sonoda H, Yamaoka M, Tachibana K, Hirato T, Sato Y (2019) Iduronate-2-Sulfatase with Anti-human Transferrin Receptor Antibody for Neuropathic Mucopolysaccharidosis II: A Phase 1/2 Trial. Mol Ther 27:456–464.

9. Jiao Y, Yang L, Wang R, Song G, Fu J, Wang J, Gao N, Wang H (2024) Drug Delivery Across the Blood–Brain Barrier: A New Strategy for the Treatment of Neurological Diseases. Pharmaceutics 16:1611.

10. Terstappen GC, Meyer AH, Bell RD, Zhang W (2021) Strategies for delivering therapeutics across the blood–brain barrier. Nat Rev Drug Discov 20:362–383.

11. Wu D, Chen Q, Chen X, Han F, Chen Z, Wang Y (2023) The blood–brain barrier: Structure, regulation and drug delivery. Sig Transduct Target Ther 8:217.

12. Hazleton JE, Berman JW, Eugenin EA (2010) Novel mechanisms of central nervous system damage in HIV infection. HIV AIDS (Auckl) 2:39–49.

M365 Copilot was used to help reword some sentences for clarity and to find references.

Cover photo by evening_tao from Freepik.

Figures 1 and 2 made by Anna Kasper in Biorender.

Leave a comment