October 14th, 2025

Written by: Julia Riley

If there’s one thing people tend to remember from high school biology, it’s the catchphrase “mitochondria are the powerhouses of the cell”. Mitochondria (singular: mitochondrion) are organelles, or structures that exist within our cells to perform specific jobs much like organs do in the larger context of the body. As this pithy phrase suggests, mitochondria generate the molecular-level fuel that the trillions of cells in your body use to power their functions and stay alive.

While these widely loved little components of our cells are certainly the powerhouses behind many neurological processes, they are also crucial for maintaining our health. Beyond their normal function of generating fuel for cells, mitochondria also participate in a wide variety of signaling pathways, or molecular methods that cells use to communicate both within themselves and with other nearby cells. Here, we discuss how mitochondria perform their major job of making fuel, some of the lesser-known cellular functions they participate in, and why this might be important for our understanding of neurological diseases like Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s.

What do mitochondria actually look like?

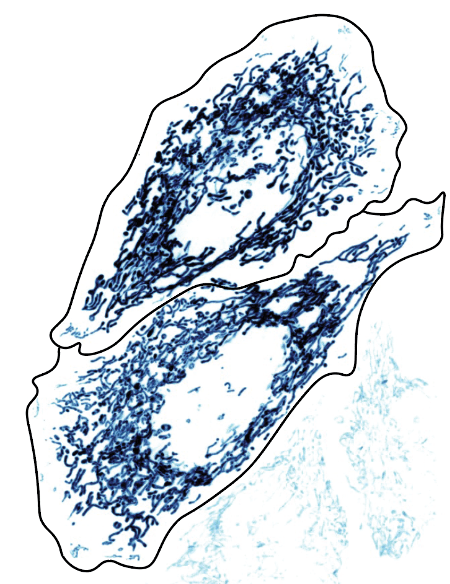

Biology textbooks tend to picture mitochondria as one or two little kidney bean-shaped structures with what looks like a squiggle on them. In reality, mitochondria exist in cells as an extensive, inter-connected network that is constantly being molded and reshaped to adapt to what a cell needs (Figure 1). When healthy and functioning, mitochondria are elongated, tube-like structures that resemble spaghetti. When damaged, this network becomes fragmented, and the remaining pieces of mitochondria become isolated, spherical structures (Figure 2)1.

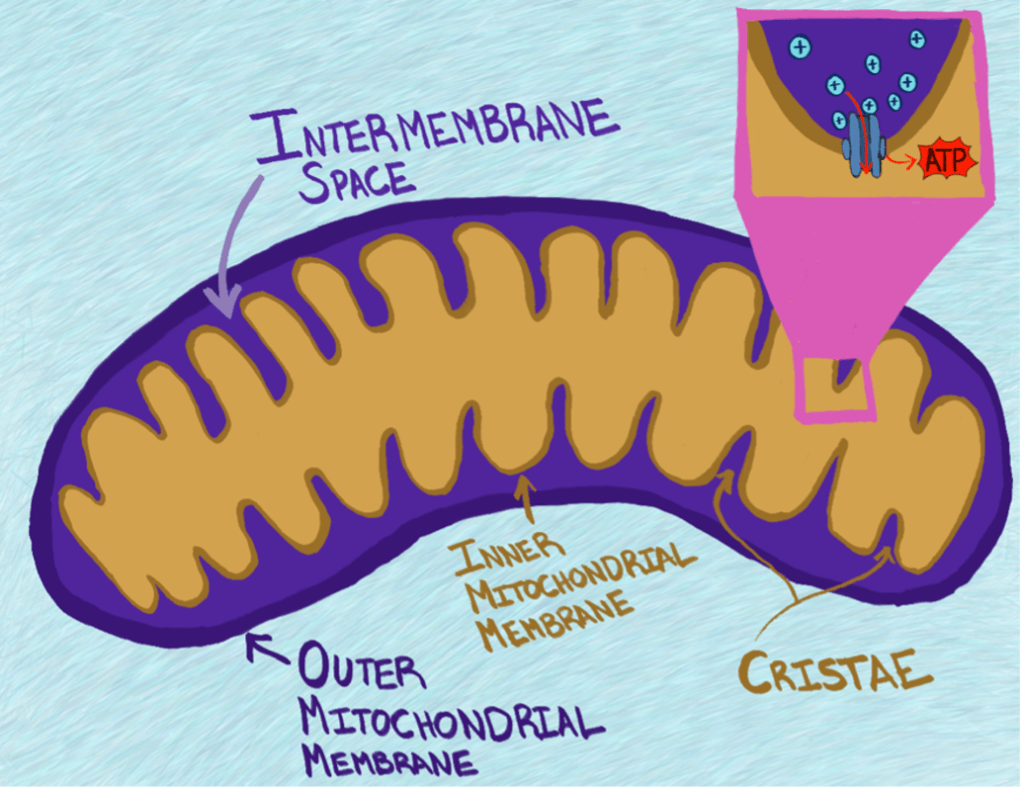

While most textbooks provide an oversimplified picture of mitochondria, they do accurately capture a key structural feature: mitochondria have two separate layers of fat that protect the inside of the organelle from the outside cellular environment. These layers of fat are called membranes The membrane on the outside, called the outer mitochondrial membrane, is the smooth structure that is large enough to be seen in microscope images like Figure 1. The membrane on the inside, intuitively called the inner mitochondrial membrane, is crinkled up into a groovy layer of fats. These grooves are so important to the structure of mitochondria that they have their own special name- cristae (pronounced kris-tay; Figure 3). The inner mitochondrial membrane contains the many little molecular machines that do the mitochondrion’s most famous job of producing energy in the form of a chemical called Adenosine Triphosphate (ATP). This ATP can be used by other molecular machines in the cell to power the hard job of staying alive and healthy.

How do mitochondria produce energy in the form of ATP?

Mitochondria are intricately designed for a reason- each component of mitochondrial structure plays a unique role in the process of ATP synthesis. The inner mitochondrial membrane does a very important job: it helps keeps protons (tiny, positive molecules) confined to the space inside the mitochondrion that sits between the inner and outer mitochondrial membranes, called the intermembrane space2, and out of the innermost space of the mitochondrion, called the matrix (Figure 3). Much like you might feel a strong urge to leave a crowded room at a party and go to a less crowded space so you have room to breathe, molecules like protons very much prefer to be dispersed evenly across the spaces available to them. If one space has very few protons and another is packed with them, those protons will readily move to the less populated space when given an opportunity. By leveraging this desire for protons to move to a less crowded space, mitochondria are able to create something called a proton gradient across their inner membrane. The existence of this proton gradient is critical for the production of ATP. The molecular machine that creates ATP is embedded in the inner mitochondrial membrane, is shaped like a tunnel, and is powered by protons pushing their way through it to get to the less crowded matrix2. You can think of this ATP-generating machine like a water wheel that generates energy when water pushes through it to flow downhill. Separate molecular machines are in place to forcibly pump these protons back out into the crowded intermembrane space, kind of like you would have to force water to move back uphill, to maintain the proton gradient.

When either the inner or outer mitochondrial membrane is damaged, holes can form in the membrane. This is a problem because it means that protons are able to escape from the crowded intermembrane space without being forced to flow through the molecular machine that makes energy1. To understand why this is an issue, imagine a river that breaks into 10 streams before coming back together. If you place a water wheel at the top where all the water is coming through, you’ll produce much more energy than if you’re forced to place your water wheel on one of the smaller streams that has only some of the river’s water passing through. When there are holes in the mitochondrial membranes, protons have alternative avenues to get to a less crowded space, and the mitochondrion ceases to function properly because protons are no longer being forced through the molecular machine that makes ATP. Mitochondrial damage in neurons is widely believed to be a key contributor to neurodegenerative diseases like Alzheimer’s disease and Parkinson’s disease, and therapies aimed to make these mitochondria healthier have been proposed as potential avenues for treating these disorders.

Mitochondria are hubs for cellular- and nervous system- health.

Due to their central role of producing energy for almost all internal cell-level processes, mitochondria are central to the function of many cells. However, they’re especially important for neurons. Compared to other cell types, many neurons absolutely guzzle energy13,14. Constantly sending signals back and forth is hard work.

Additionally, neurons have a specialized shape with lots of branches (Figure 4), some of which can extend over five feet!15. This means that neurons also need energy to transport necessary materials, so that each part of the neuron has what it needs to stay happy and healthy. Mitochondria not only provide energy for things to be carried down molecular highways all the way to where they need to go, but they themselves are often carried to various locations in the neuron so that they can locally produce energy for various molecular processes (Figure 4) 16–18. Just like it is more convenient for you to find fuel if there’s a gas station in your town instead of two counties over, it’s more convenient for the molecular machines in your neurons to find the fuel they need to function if there is a mitochondrion close by and functioning. In fact, having mitochondria located close to the part of the neuron that releases chemicals to communicate with other neurons has been shown to impact the efficiency of this signaling13,19,20.

What do mitochondria do other than generate energy for the cell?

In addition to making ATP to power molecular machines in the cell, mitochondria are involved in a diverse array of cellular happenings. Typically, mitochondria use molecules derived from the breakdown of sugars to fuel their proton gradient, but they also contain a different set of machinery that helps break down fats for energy. Mitochondria also form close contacts with other types of organelles in the cell, allowing them to influence other jobs that they don’t actually perform themselves. These jobs include such as breaking down protein and shipping materials to other cells4.

Potentially one of the most interesting things about mitochondria is that they can activate your cell’s molecular-level immune responses5–7. Just like your body has an immune system, your cells have built-in measures to help ward off potentially dangerous invaders. Activation of this cell-level immune system can result in a cell dying- this is so that the invader won’t have a place to live anymore, and will hopefully die off as well. While this is beneficial to a human’s overall well-being when the cells in question can easily be replaced (like a skin cell), it becomes much more problematic when the injured cells are neurons, which (with very limited exceptions) are never regenerated by your body no matter how many are lost. Mitochondria can initiate this cellular-level immune signaling8–10, and as you get older, the mitochondria in your neurons get worse at making ATP and start activating the cellular immune system more potently11,12. This is important because if it occurs to a drastic extent in brain cells like neurons, it can cause those neurons to die.

The fact that mitochondria become more inclined to initiate immune system signaling as you grow older is thought to be a key factor that contributes to the onset of age-related, neurodegenerative diseases like Alzheimer’s or Parkinson’s that don’t typically present any symptoms until a patient is at least middle-aged. The thought is that a decrease in proper mitochondrial function might weaken the health of neurons. This is bad because it could make neurons more susceptible to damage from exposure to something like an environmental toxin. Alternatively, if a neuron is already functioning incorrectly for some reason, mitochondrial malfunction can worsen their health further and potentially accelerate their death. In fact, mitochondrially targeted therapies have been of increasing interest for these diseases, since there is quite a bit of evidence linking several neurodegenerative diseases to an abnormally drastic decline in the health of mitochondria in neurons. Research using neurons grown in a dish has shown that increasing mitochondrial health, or even just expediting the removal of damaged mitochondria, can bolster cellular health overall21. In mice that have been genetically altered to develop Alzheimer’s disease, enhancing mitochondrial function improves cognitive abilities like memory and learning22.

Overwhelmingly, these studies suggest that mitochondria are indeed the powerhouses of your cells- in many more ways than one.

References

1. Chen, W., Zhao, H. & Li, Y. Mitochondrial dynamics in health and disease: mechanisms and potential targets. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 8, 333 (2023).

2. Ahmad, M., Wolberg, A. & Kahwaji, C. I. Biochemistry, Electron Transport Chain. in StatPearls (StatPearls Publishing, Treasure Island (FL), 2025).

3. Talley, J. T. & Mohiuddin, S. S. Biochemistry, Fatty Acid Oxidation. in StatPearls (StatPearls Publishing, Treasure Island (FL), 2025).

4. Friedman, J. R. & Nunnari, J. Mitochondrial form and function. Nature 505, 335–343 (2014).

5. Weinberg, S. E., Sena, L. A. & Chandel, N. S. Mitochondria in the regulation of innate and adaptive immunity. Immunity 42, 406–417 (2015).

6. Marques, E., Kramer, R. & Ryan, D. G. Multifaceted mitochondria in innate immunity. Npj Metab. Health Dis. 2, 1–15 (2024).

7. Angajala, A. et al. Diverse Roles of Mitochondria in Immune Responses: Novel Insights Into Immuno-Metabolism. Front. Immunol. 9, 1605 (2018).

8. Garrido, C. et al. Mechanisms of cytochrome c release from mitochondria. Cell Death Differ. 13, 1423–1433 (2006).

9. Huang, P. et al. Mitochondrial DNA drives neuroinflammation through the cGAS-IFN signaling pathway in the spinal cord of neuropathic pain mice. Open Life Sci. 19, 20220872 (2024).

10. Kim, J., Kim, H.-S. & Chung, J. H. Molecular mechanisms of mitochondrial DNA release and activation of the cGAS-STING pathway. Exp. Mol. Med. 55, 510–519 (2023).

11. Chistiakov, D. A., Sobenin, I. A., Revin, V. V., Orekhov, A. N. & Bobryshev, Y. V. Mitochondrial Aging and Age-Related Dysfunction of Mitochondria. BioMed Res. Int. 2014, 238463 (2014).

12. Srivastava, S. The Mitochondrial Basis of Aging and Age-Related Disorders. Genes 8, 398 (2017).

13. Faria-Pereira, A. & Morais, V. A. Synapses: The Brain’s Energy-Demanding Sites. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 23, 3627 (2022).

14. Pulido, C. & Ryan, T. A. Synaptic vesicle pools are a major hidden resting metabolic burden of nerve terminals. Sci. Adv. 7, eabi9027 (2021).

15. Guedes-Dias, P. & Holzbaur, E. L. F. Axonal transport: Driving synaptic function. Science 366, eaaw9997 (2019).

16. Aiken, J. & Holzbaur, E. L. F. Cytoskeletal regulation guides neuronal trafficking to effectively supply the synapse. Curr. Biol. 31, R633–R650 (2021).

17. Li, S., Xiong, G.-J., Huang, N. & Sheng, Z.-H. The cross-talk of energy sensing and mitochondrial anchoring sustains synaptic efficacy by maintaining presynaptic metabolism. Nat. Metab. 2, 1077–1095 (2020).

18. Fenton, A. R., Jongens, T. A. & Holzbaur, E. L. F. Mitochondrial adaptor TRAK2 activates and functionally links opposing kinesin and dynein motors. Nat. Commun. 12, 4578 (2021).

19. Pathak, D. et al. The Role of Mitochondrially Derived ATP in Synaptic Vesicle Recycling*♦. J. Biol. Chem. 290, 22325–22336 (2015).

20. Vos, M., Lauwers, E. & Verstreken, P. Synaptic Mitochondria in Synaptic Transmission and Organization of Vesicle Pools in Health and Disease. Front. Synaptic Neurosci. 2, (2010).

21. Hu, H. & Li, M. Mitochondria-targeted antioxidant mitotempo protects mitochondrial function against amyloid beta toxicity in primary cultured mouse neurons. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 478, 174–180 (2016).

22. Pagano Zottola, A. C. et al. Potentiation of mitochondrial function by mitoDREADD-Gs reverses pharmacological and neurodegenerative cognitive impairment in mice. Nat. Neurosci. 28, 1844–1857 (2025).

All figures and images were generated by the author (Julia Riley).

Leave a comment