October 7th, 2025

Written by: Emma Noel

To understand why conspiracy theories emerge, we have to understand how our belief systems shape the way we interact with the world around us. We all have our belief systems. While most of us can agree that the sky is blue, not every belief we hold is so trivial. Our beliefs shape how we interpret the world and the choices we make, including who we choose to spend time with. Beliefs guide us toward people who think like we do, people we turn to for advice and validation. That camaraderie often reinforces what we already thought, making our views feel even more certain. This is why, when we’re faced with counterarguments, or even strong evidence against something we believe, it can be easy to dismiss it as false. Belief systems can be comforting, helping us build community and connection, but they can also become dangerous if left unchecked. In this article, I’ll explore some popular conspiracy theories, and why our brains are wired to seek like-minded information while rejecting outside evidence.

What counts as a conspiracy theory?

A conspiracy theory is a theory that explains an event or set of circumstances as the result of a secret plot by usually powerful conspirators.1 Conspiracy theories often arise out of the desire to seek a deeper meaning or understanding of something uncertain or confusing. They tend to emerge during times of uncertainty or when official explanations feel incomplete, offering a sense of order or purpose to chaotic events. Some are short lived, while others grow into sprawling narratives that can shape how entire groups see the world. Regardless of who you are, you’ve probably believed a conspiracy theory at some point. Even the most far-fetched theories can make us pause and question what we thought we knew. I found myself deep in a Reddit rabbit hole on why the movie The Shining proves that Stanley Kubrick staged the moon landing. While I know for a fact that the moon landing was real, today I am going to tell you more about why these theories sound attractive and how they take up space in our brains.

Conspiracy theories come in many forms. Some are lighthearted, like the idea that Avril Lavigne was secretly replaced by a body double or that birds aren’t real, which are fun to joke about with friends. Others touch on serious scientific or political issues, such as claims that COVID-19 was engineered in a lab or that global warming is a hoax. No matter the scale, conspiracy theories are surprisingly common. Surveys suggest that more than half of Americans believe in at least one conspiracy theory, and belief often varies by political party, education, and trust in institutions.2

Why our brains believe conspiracy theories

Conspiracy theories are attractive not just because of the claims they make, but also because of psychological and social mechanisms, such as how our brains process new information and relate in social groups. Here we’ll discuss three of these contributing factors:

Confirmation bias

Confirmation bias is the tendency to search for and remember information that confirms what we already believe and neglect or misinterpret information that is contradictory to what we believe. One example of this is only reading news from a single outlet that you know aligns with your political views. This helps a conspiracy theory take hold by filtering information so that only evidence supporting the theory is recognized, and anything contradicting the theory is dismissed as unreliable or even a part of the conspiracy theory. For example, someone who believes the moon landing was fake may highlight perceived inconsistencies in pictures or videos while ignoring historical records of the event because they believe the falsification of these records is part of the conspiracy. This selective attention reaffirms what the individual already believed, solidifying their support of the theory.3 Public Policy Polling reports that as of 2013, over a third of Americans believed that global warming is a hoax, and that belief in this theory differs across political parties.2 These differences may result in part from the kinds of media people consume and the social networks they exist in, which can strengthen preexisting views through confirmation bias.

In-group/out-group dynamics

In-group/out-group dynamics refer to the way we naturally divide other people into groups, either similar to us (the in-group) or different than us (the out-group), which strengthens our perceived alliance with the social group we identify with. Scholars suggest that belief in conspiracy theories partly arise from our need to belong to a social group.3 If your social group believes that COVID-19 was engineered in a lab, you are more likely to believe the same to maintain good standing with this social group.4 At the same time, these feelings can intensify negative emotions toward the out-group. Taking the COVID-19 was engineered in a lab theory as an example, for the people believing in this theory, it gave them a sense of belonging to a group and reduced their personal guilt about their own behaviors (such as not following masking guidelines). By pinning the responsibility on a large out-group such as scientists in Wuhan, these believers could decrease feelings of guilt while emboldening feelings of anger or distrust towards the outside world.5

Reinforcement learning

Reinforcement learning is the process by which our brain encourages us to repeat actions that have previously yielded positive outcomes. Moreover, when a behavior leads to a reward, we tend to repeat this behavior again. Imagine someone jokingly claims a new government “bird drone” will be spotted in a city. At first, the person listening may not be convinced. However, if that same person later sees a news article about increasing government drone surveillance, this may increasingly spark their interest. Then, if that same person is walking on the street later in the week and sees a drone sitting in a tree next to a bird, the coincidence may feel rewarding, strengthening their attachment to the idea, even if it started as satire. This person may find themself looking at the sky during work and eventually realize that they themselves believe that birds are not real. When more events occur that match the idea that “birds aren’t real”, even if it is coincidental, the person experiences a type of reward, or satisfaction of being correct or knowing something other people did not. This cycle strengthens the belief in the first place, thus the outcome is a reinforcement of beliefs and behaviors.6

While confirmation bias, in-group/out-group dynamics and reinforcement learning explain part of why we seek out like-minded individuals, they don’t fully capture why conspiracy theories can feel so compelling. To understand this, we can turn to how our brains are wired to facilitate these higher level processes.

Reward and the circuits underlying belief

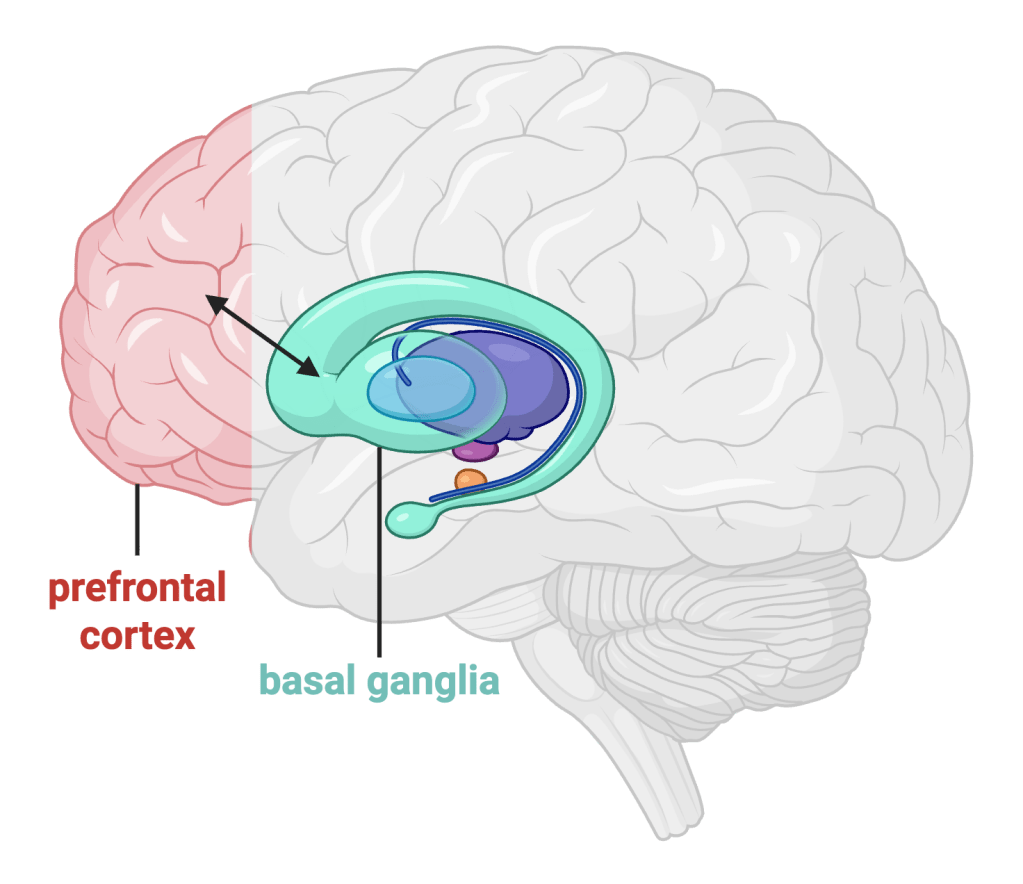

There are many parts of the brain involved in forming and reforming beliefs. Two major players are the prefrontal cortex and the basal ganglia. The prefrontal cortex is a brain region involved largely in decision making and social cognition, while the basal ganglia is involved in reinforcement learning. Specifically a subpart of the basal ganglia called the substantia nigra contains neurons that release a chemical called dopamine. When a reward or positive/correct outcome is experienced, like in the process of reinforcement learning, dopamine is released, leading to feelings of happiness or satisfaction. Some of the dopamine neurons in the substantia nigra connect with the prefrontal cortex, which the prefrontal cortex uses to adjust our beliefs, or change our behaviors to better maximize the reward the next time.7

However, not all brains are alike in processing conspiracy theories. Using fMRI, a neuroimaging technique to measure brain activity by detecting changes in blood flow, can uncover which brain areas are activated in response to a specific prompt. Researchers took volunteers and split them into two groups, one that believes highly in a range of conspiracy theories (high conspiracy believers) and another that did not believe in conspiracy theories (low conspiracy believers). This study found that high conspiracy believers had higher brain activity in the prefrontal cortex, a region involved in division-making, when exposed to conspiracy theories.8 In contrast, low conspiracy believers show more activity in the hippocampus, a region important for retrieving memories.8 This difference suggests that conspiracy information is processed in distinct ways depending on someone’s tendency to believe such ideas. It also helps explain why believing one conspiracy theory often makes a person more likely to believe others, their brains may approach and evaluate this kind of information differently from the start. Overall, this suggests different activation of neural pathways after exposure to the same theories.

In conclusion, conspiracy theories thrive not because people have a warped sense of reality, but because these theories are great at tapping into deeply rooted psychological tendencies. Confirmation bias, in-group/out-group dynamics and reinforcement learning help make these theories seem compelling, even when they are far from the truth. Understanding why conspiracy theories thrive and the neural pathways underlying them helps us not only better understand ourselves but also the biases we carry, and this knowledge even helps us counter these theories. For example, being aware of how our individual brains process conspiracy theories may help us avoid believing theories in the future, as when we are presented with new information we may pause to consider what we know to be true, and if we trust the source of information, helping control how we respond to the theory.

References

- Merriam-Webster. (n.d.). Conspiracy theory. In Merriam-Webster.com dictionary. Retrieved October 3, 2025.

- Jensen T. (2013). Democrats and Republicans differ on conspiracy theory beliefs, Public Policy Polling.

- Gagliardi L. (2025)The role of cognitive biases in conspiracy beliefs: A literature review. Journal of Economic Surveys, 39(1),e32-65

- Yoo J. H. (2025). On the Controversies Surrounding the Lab-Leak Theory of COVID-19. Journal of Korean medical science, 40(16), e153.

- Douglas K. M. et al. (2017). The Psychology of Conspiracy Theories. Current directions in psychological science, 26(6), 538–542.

- Barnby J.M. et al. (2022). The computational relationship between reinforcement learning, social inference, and paranoia. PLOS Computational Biology, 18(7), e1010326

- Seitz, Rüdiger J. (2018). Believing is representation mediated by the dopamine brain system. European Journal of Neuroscience.

- Zhao S. et al. (2025) Neural correlates of conspiracy beliefs during information evaluation. Science Reports, 15(18375).

Figure created in Biorender

Cover photo from Freepik.