May 20th, 2025

Written by: Julia Riley

Few people question the importance of research directly intended to understand or to better treat diseases; chronic or terminal illnesses have harmed so many lives that it is often easy to picture why this is a priority amongst scientists. In fact, the application of this type of work is so clear that it might leave you wondering: why do we also so avidly pursue basic research, or work that aims to uncover fundamental truths about why our universe and our bodies work the way they do?

Although clinical research is certainly necessary to improve our treatments for disease, there is still a lot about our world that we don’t yet understand. This leaves us with countless instances where we lack either the knowledge or technology to develop effective methods to diagnose and treat disease. It is for precisely this reason that many of our most revolutionary clinical breakthroughs in recent history were actually borne from basic research. Without basic research, we would entirely lack the knowledge and tools necessary to push the boundaries of disease treatments. While clinical research is often intended to better existing approaches, basic research can provide entirely new avenues to pursue. You can imagine this as being like the difference between an athlete trying to scale a mountain in shorts and a t-shirt, versus that same person being provided with appropriate clothes and tools. Basic research can change our likelihood of accomplishing something from impossible to probable simply by providing us with entirely new options and approaches.

Several of our most important clinical breakthroughs began as basic research, and these curiosity-driven questions without clear clinical goals have since grown into important discoveries that are actively shaping the future of modern medicine. These breakthroughs serve as evidence that basic research is absolutely necessary to continue funding and pursuing if we want the best possible chance to develop new, effective cures for diseases that we cannot currently treat. Here we discuss two of these breakthroughs and dive into how they are improving the treatment and prevention of neurological (and other) diseases today.

CRISPR/Cas9: Giving a prehistoric immune system the “gene editing tool” edit

The gene editing tool CRISPR/Cas9 (pronounced Kris-per Kah-s Nine) made international headlines in 2020 when the two scientists credited with discovering it and refining our ability to use it to our advantage were awarded a Nobel Prize. This technology has revolutionized our methods for researching genetic diseases, and has even been used clinically to treat a blood disorder called sickle cell disease1 and save the life of a six-month-old boy with a metabolic disorder2. However, this game-changing technology had far more humble beginnings than one might expect.

Back in 1993, a Spanish researcher named Francisco Mojica became fascinated with a peculiar feature of tiny, single-celled organisms called archaea that populated the marshes near the place he grew up3. Mojica was studying the DNA of these archaea. DNA is the information contained in the cell(s) of living organisms that provide information necessary to make all of the molecules needed to live, kind of like a recipe book for the different molecules a cell can use to carry out everyday tasks. Typically, DNA is composed of four unique molecular building blocks called bases that are represented by the letters A, T, G, and C. These bases lie in a specific order along what is referred to as a strand of DNA- if DNA were a book, the bases would be the letters and strands of DNA would be the sentences. DNA is stored in cells as two strands wrapped around each other, with an “A” on one strand always lined up to “T” on the other, and with “G” always lined up to “C”. This means that you can tell what the sequence of bases is on one strand by checking out the sequence of bases on its opposing strand.

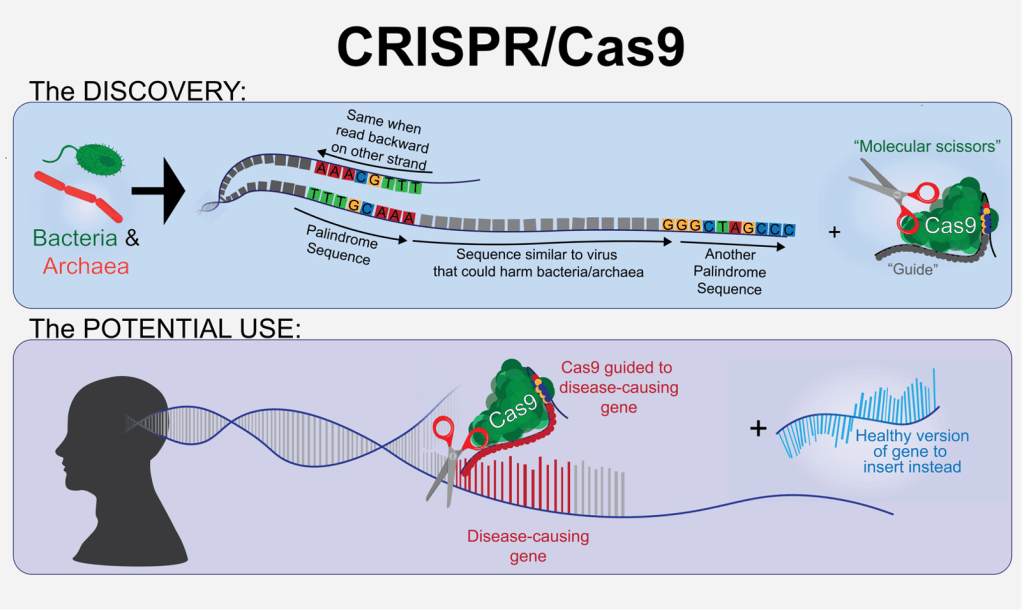

The bases in DNA are not typically arranged in any pattern that would be apparent to an observer. However, Mojica noticed that much like the words “racecar” and “madam”, there were some bases of the DNA in the archaea he studied that were arranged into palindromes, or something that can be read backwards or forwards and still form the same sequence of letters. In the context of DNA, this looks like sequences that are identical on both of the intertwined strands of DNA when read in opposite directions (Figure 1). These palindromic sequences, which were named CRISPR (short for “Clustered Regularly Interspaced Short Palindromic Repeats”), were typically separated from each other along the strand of DNA by ~35 seemingly random bases3.

Mojica was curious as to why the DNA in these archaea would be arranged in such a way. He found that many of the seemingly random sequences separating the palindromes in the DNA were identical to the DNA sequences that certain viruses use to infect and kill single-celled organisms like archaea. This caused him to speculate that these sequences were somehow involved in the ability of single-celled organisms to fend off viruses, kind of like our immune system as humans prevents us from getting sick.

This discovery sparked several groups’ interest in a basic question- exactly how do single-celled organisms like archaea fend off infections? Although it is certainly far removed from the very complex human immune system, several researchers became fascinated with understanding this on a deeper level. Further research clarified that the way this (literally) archaic, miniature immune system works is by collaborating in tandem with another molecule named Cas9. Cas9 functions kind of like molecular scissors; the DNA containing the alternating palindrome sequences and sequences resembling viruses act as guides used to recognize possible invaders, and Cas9 uses these guides to identify invading viruses, which it can then cut up and destroy4.

You might be thinking- it’s cool that single-celled organisms like archaea can have immune systems, but why does that matter for humans? In order to study diseases and potential treatments we need to recreate them, and this is often done by editing the DNA of whatever organism the lab is using to study the disease. A major step in our DNA editing process in the laboratory is cutting DNA in the right place to make room for a new sequence to be inserted, kind of like you might cut a nonsensical sentence out of the middle of a paragraph and replace it with a new one that can be read correctly. CRISPR/Cas9 can do precisely that: recognize a specific part of DNA and proceed to cut it. This means that we can isolate and use the CRISPR/Cas9 system to make gene editing in mammals far easier than it once was. This newfound simplicity of the gene editing process has made it possible for us to edit DNA in many contexts where we couldn’t before; previous methods to accomplish this same feat entailed many more steps, and each additional step introduced some degree of risk to the integrity of the procedure. This means that we can now use gene editing in animals like mice to help us better recreate and study disease and, in some instances, can even perform gene editing in humans where a typo in their DNA is causing debilitating illness. If Francisco Mojica had never posed the simple question of why there are palindromes in the DNA sequences of archaea, we may not have developed this powerful tool.

Two scientists named Jennifer Doudna and Emmanuele Charpentier are credited with recognizing the potential of this technology for gene editing and for deeply characterizing CRISPR/Cas9. The pair would later win the aforementioned Nobel Prize in Chemistry. Later, other researchers like Feng Zheng’s group at MIT worked to optimize use of CRISPR/Cas9 to the point where it could be used in mammals like mice5, which was a critical step toward our current capabilities to use this technology in hospitals to combat disease. If we cannot confirm that a technology works safely in animals like mice, it almost certainly will not receive approval to be used in people.

Thanks to the many scientists along the way who had the curiosity about bacteria and archaea to ask how they fought disease and the others who had a vision about repurposing this process to work in our own cells, we now have the most efficient gene-editing technology ever created. This is important for at least two major reasons- the first is that it has already been optimized enough to enable faster gene editing in research, which lets us study various illnesses more effectively. The second is that it can be used to treat patients whose ailments are attributable to typos in their DNA. As previously mentioned, we already use CRISPR/Cas9 in certain medications intended to treat sickle cell disease, and just recently used it in a personalized approach to help treat a young boy with a severe metabolic disorder. With optimization, we might be able to one day use this technology to help treat an even greater number of debilitating genetic diseases. In practical terms, this looks like people born with genetic blindness being able to see, and people born with heritable forms of diseases like Alzheimer’s being able to retain their autonomy into old age.

fMRI: Spinning atomic spin into a diagnostic tool

You may have heard of people getting a “brain scan” or seen the beautiful, multi-colored brain images that depict which parts of the brain are working during a given task. These images are produced using a clinical technology called functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI).

The technology underlying our ability to scan brains was originally discovered as an attempt to better understand atoms, the tiny building blocks that make up our universe. Atoms essentially function like very tiny magnets, and their negative or positive charges allow them to stick to one another to make the materials that occupy our world. Scientists predicted that because atoms are essentially tiny magnets, hitting them with external magnetic pulses would cause them to spin just like refrigerator magnets do when you move them around near each other. They found that this was true, and discovered another curious phenomenon in the process; when the magnets stop and the atoms are allowed to relax back into their normal state, they emit energy that can be detected6. That isn’t all- it was found that the speed with which the atoms spin in response to a magnetic pulse is dependent on how exposed to the magnet they are. Kind of like a raincoat shields you from rain, atoms that are directly next to other atoms with certain properties can be shielded from the magnet. This shield will cause the atom to spin less quickly than an atom that is fully exposed. The change in speed also changes the amount of energy the atom emits when it relaxes back to its normal state- because the shielded atom spun less quickly, it has less energy to emit on its way back to its normal state. The different amounts of energy being released can be picked up by a detector. This can help scientists and doctors determine what and where a specific molecule is, and it even makes it possible to pick up on the location of molecules that are floating around inside a person.

In the late 1960s through the 1970s, it dawned on researchers that this principle could be used to detect water, and that different tissues in the body absorb water differently. This means that the water in different organs would look different to a detector because the water molecules in each organ spin differently in response to magnetic pulses7. Scientists learned we are able to use this to distinguish between different parts of the body and recreate an image of what is going on within internal organs. Through decades of refinement, these discoveries gave way to the modern-day medical technique we know as MRI. Even further refinement of the MRI machine led to the technique known as fMRI that we can use to detect blood flow in the brain, which serves to represent which areas of your brain are most active8.

Since its development, fMRI has become a crucial tool for both neuroscientists and doctors. This brain scanning technique helps doctors figure out the location of tumors and diagnose disorders like epilepsy. It is also enabling scientists to better study potential treatments for mental illnesses like major depressive disorder (depression) and anxiety disorders, which in and of themselves impact almost one in four Americans each year. fMRI is arguably our most important tool for gathering initial information on how the brain might help us accomplish specific tasks.

fMRI is also critical in ensuring the safety and efficacy of many neurological procedures- the brain is a very sensitive organ, and neurosurgeons need to be careful when operating to avoid disturbing brain tissue unnecessarily. This is made even more complicated by the fact that the shape and structure of everyone’s brain is slightly different; just like other parts of our bodies like our hands, no two brains are exactly the same. Going into a brain surgery blind could mean a lot of extra searching and cutting, which could easily result in serious harm or impairment to the patient when done in such a delicate organ. Previous methods of ensuring that brain surgery was being performed in the correct spots were incredibly invasive, with some requiring that the patient be awake and responsive for the full duration of their surgery. Despite numbing the area, this can be incredibly stressful and tedious for the patient. It can also pose additional challenges for the surgeon, who might have to make real-time adjustments to the surgical plan. To make surgeries less invasive while still minimizing unnecessary cutting and searching, surgeons can use fMRI to locate the precise source of an issue like a tumor on an individualized, patient-to-patient basis9. This helps them carefully plan out an approach to each surgery that minimizes the patient’s risk.

Without scientific interest in the magnetic properties of the molecules that make up our universe, we would not have been able to produce technology like MRI and fMRI. Scientific discoveries regarding the fundamentals of magnetism and energy release as they pertain to the building blocks of our world have empowered us to diagnose diseases we couldn’t otherwise identify, understand brain function on a more advanced level, and plan out surgeries so as to minimize the cutting that has to be done. What was once a question about how atoms spin has turned into a versatile and powerful technique for researchers and clinicians alike.

Conclusion

These are only two examples of how basic research has furthered our ability to combat disease and bettered our lives in the process. Given the foundations upon which both fMRI and CRISPR/Cas9 were built, it easy to imagine that there are likely many other areas where we continue to lack the fundamental knowledge necessary to develop a cure for a given disease or definitively diagnose a specific injury. It once seemed impossible to cure genetic disorders, but thanks to work that started as a curiosity-driven investigation into how single-celled organisms fight invading viruses, doctors were recently able to save the life of a six-month-old baby with a metabolic disease. We had very limited methods for non-invasively understanding how different brain areas contribute to (or, in the case of disease, hinder) our ability to function before a series of scientists became interested in energy release by the molecules that make up our universe. There is a real possibility that many of the diseases that we cannot currently cure are not treatable because we are missing a critical piece of the puzzle that will never fall into place without basic research.

Basic research is necessary to ensure that we continue fortifying the foundation of knowledge upon which so many of our most groundbreaking clinical developments are built. As we continue to perform research intended to demystify the world around us, we will continue to build a progressively more robust toolbox for battling all kinds of illness. Funding and conducting basic research will continue to yield new and previously unimaginable tools that will help us surmount many of the obstacles that the human race faces, including illnesses that are not currently treatable.

References

1. Commissioner, O. of the. FDA Approves First Gene Therapies to Treat Patients with Sickle Cell Disease. FDA https://www.fda.gov/news-events/press-announcements/fda-approves-first-gene-therapies-treat-patients-sickle-cell-disease (2024).

2. Philadelphia, T. C. H. of. World’s First Patient Treated with Personalized CRISPR Gene Editing Therapy at Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia | Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia. https://www.chop.edu/news/worlds-first-patient-treated-personalized-crispr-gene-editing-therapy-childrens-hospital.

3. Lander, E. S. The Heroes of CRISPR. Cell 164, 18–28 (2016).

4. Barrangou, R. & Doudna, J. A. Applications of CRISPR technologies in research and beyond. Nat. Biotechnol. 34, 933–941 (2016).

5. Cong, L. et al. Multiplex Genome Engineering Using CRISPR/Cas Systems. Science 339, 819–823 (2013).

6. A mini review of NMR and MRI. https://arxiv.org/html/2401.01389v1.

7. History of MRIs and the Evolution of This Life-Saving Technology – Ezra. https://ezra.com/blog/history-of-mri-scans.

8. Bandettini, P. A., Wong, E. C., Hinks, R. S., Tikofsky, R. S. & Hyde, J. S. Time course EPI of human brain function during task activation. Magn. Reson. Med. 25, 390–397 (1992).

9. Abu Mhanna, H. Y. et al. Systematic review of functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) applications in the preoperative planning and treatment assessment of brain tumors. Heliyon 11, e42464 (2025).

Figure1 was created in Adobe Illustrator by author (Julia Riley).

Thumbnail photo was generated with Gemini (by Google).

Leave a comment