May 6th, 2025

Written by: Stephen Wisser

If you are of legal drinking age, perhaps this is a familiar scenario. You’ve had a few drinks out or with friends at a house party and you thought you did a good job of pacing yourself. But the next morning you awake with a headache, dry mouth, dizziness, and some feelings of nausea – oh no, the dreaded hangover! With descriptions of hangovers appearing in the Old Testament and writings of ancient Egypt1, you might think there’s been enough time for scientists to understand hangovers and create a cure, but that’s not the case. It turns out hangovers are really hard to study. Since a hangover is different for everyone and typically consists of a variety of symptoms, determining when a hangover starts is extremely difficult2, which makes it hard to conclude exactly what caused the hangover. As a result, scientists don’t have a good idea of what causes hangovers and can only investigate this unique experience by studying things that are associated with common hangover symptoms. In this post, we’ll explore 3 mechanisms that scientists think might be responsible for hangovers, as well as some animal studies that are beginning to shed more light on this mysterious condition.

Booze in the Brain

To a chemist, alcohol can be many different chemicals, some that are quite different from one another. In common everyday speech, when we say “alcohol”, we are technically referring to one type of alcohol called ethanol, the main alcohol found in wine, beer, and liquor. To keep things simple, for the rest of this post I’ll only discuss experiments involving ethanol and refer to it as alcohol. The effects of alcohol and how it works in the brain are covered in great detail in this previous post, but we need a quick refresher to understand a major factor that scientists believe might influence hangover symptoms.

Alcohol is commonly thought of as a depressant. This is because when alcohol enters the brain, it activates the brain’s GABA system. The brain’s GABA system is responsible for releasing the neurotransmitter GABA, a chemical signal that inhibits, or quiets brain activity. So, when alcohol activates the GABA system our brains experience a greater amount of inhibition. Opposite to GABA is the glutamate system, which contains neurons that release the neurotransmitter glutamate. Glutamate does the opposite of GABA and generally excites or activates the brain.

In a healthy brain, there is a careful balance of GABA and glutamate release, but during long-term alcohol exposure, as the brain is bathed in more GABA than usual, the brain releases more glutamate to counteract the overactive GABA signaling caused by alcohol1. Even after alcohol is cleared from the body, the body continues to release lots of glutamate3 which causes withdrawal symptoms, many of which also occur in hangovers. Although this situation applies to heavy drinking, scientists believe that hangovers from less frequent alcohol use are essentially a “mini-withdrawal” and partly due to an imbalance of GABA and glutamate like what is seen in chronic drinking.

Alcohol Breakdown: The Metabolites

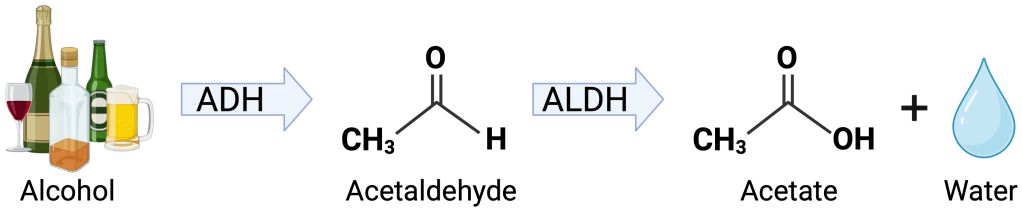

In addition to the alcohol itself in the brain, a lot of hangover attention has been given to the chemicals that alcohol becomes when it is broken down by the body, called metabolites. As shown in Figure 1, alcohol is first broken down into acetaldehyde, which is then broken down to acetate. On one hand, scientists have good reason to think that acetaldehyde is a main culprit in producing hangover symptoms. For one, acetaldehyde is very toxic to humans and is known to cause damage to cells4. Additionally, some people experience hangover-like symptoms soon after drinking only a small amount of alcohol. In these people, the quickly occurring hangover like symptoms are caused by a genetic mutation that slows the breakdown of acetaldehyde5, suggesting that the acetaldehyde that sticks around longer as a result is a problem.

On the other hand however, there is evidence to suggest that acetaldehyde isn’t really a big player. In humans, scientists found no association between acetaldehyde levels in people’s blood and hangover severity6. Additionally, acetaldehyde is quickly broken down into acetate2, which means that the acetaldehyde initially produced by breaking down alcohol doesn’t stick around in the body long. So even though acetaldehyde is a known toxin, perhaps it doesn’t remain long enough in the body to cause problems. Finally, scientists now believe that acetaldehyde actually doesn’t pass through the blood brain barrier7 (barrier discussed in this excellent post) which means that any acetaldehyde produced in the body wouldn’t be able to get into the brain and wreak havoc on neurons. Although it is believed that acetaldehyde would have to enter the brain to have a role in producing hangover symptoms7, acetaldehyde could have effects outside the brain that cause hangovers. For now though, it’s safe to say the jury is still out on acetaldehyde’s role in hangovers.

After being broken down to acetaldehyde, alcohol is further broken down to its end point, acetate, another possible candidate to blame for hangovers. But, like acetaldehyde, the evidence is not conclusive. In one experiment, researchers found that administering acetate increased the development of pain in rats8. In humans, increased acetate in the blood was similarly found to be associated with headaches9. And unlike acetaldehyde, acetate does cross the blood brain barrier7, meaning acetate can get into the brain. However, acetate is generally thought of as safe and non-toxic7. It is used as a food preservative and is a naturally occurring molecule that is used to produce energy for the body. So, it seems counter-intuitive that something that is needed for healthy body functioning would be toxic. Perhaps there is something unique about increased acetate produced by breaking down alcohol that could contribute to a hangover, but further experiments are needed to say for sure.

Inflammation

The 3rd and final element we’ll discuss that scientists think might be involved in a hangover is inflammation. Inflammation is a natural process that allows the body to heal in response to an injury or illness. However, inflammation can also lead to a variety of hangover symptoms like headache, vomiting, and nausea, and alcohol is known to affect inflammation2. Scientists found that in rats, injecting alcohol increased molecules known to cause inflammation in certain brain regions just 3 hours after injecting alcohol10. A similar elevation in inflammation molecules was found in humans after drinking alcohol11, suggesting that this effect might also occur in people. In another study, scientists found that administering alcohol to mice caused an increase in similar inflammation-promoting molecules around the time when the alcohol was broken down12. A hangover typically occurs once alcohol is broken down, so since these scientists found inflammatory molecules specifically around the time when a hangover might start in humans, this suggests inflammation could be a key factor in hangovers.

Hangover Cures: Fact or Fiction?

With the complexity of hangovers discussed in this post, it is no wonder that a hangover treatment hasn’t been created yet. Yet stories abound with people’s favorite hangover remedies that they swear by. To conclude, let’s see what the science has to say about supposed hangover cures.

One of the more popular claims of a hangover cure is drinking an electrolyte beverage either after an evening of drinking or the next morning. These are things like Gatorade, Pedialyte, and Liquid IV, which are all beverages (or powders mixed with water) that replenish important salts (electrolytes) our body needs after dehydration. Alcohol is a known diuretic1 which means that it actively reduces the amount of water our body recycles and as a result increases urine production. This dehydration is one reason why people often experience frequent bouts of urination while drinking, typically accompanied by symptoms like dizziness, thirst, and lightheadedness, which are all things experienced during a hangover1. So, it might seem that one of these electrolyte beverages could fight that alcohol-induced dehydration and prevent or help a hangover. However, in one study involving humans, scientists found that was not actually the case. By analyzing various molecules in blood, these researchers found that electrolytes and a marker of dehydration did not predict the severity of a hangover,13 suggesting that the amount of electrolytes didn’t really influence how bad the hangover was. Although alcohol is a diuretic and it would make sense that counteracting dehydration with an electrolyte drink would work, in practice that doesn’t seem to be the case.

The final “cure” we’ll explore are hangover pills that claim to help reduce or eliminate the severity of a hangover. The main ingredient in many of these pills is dihydromyricetin, or DHM, which is a naturally occurring compound found in plants like the Chinese vine tea and Japanese raisin tree14. While traditionally used as an herbal medicine in Asian cultures, DHM is gaining popularity for its supposed hangover prevention properties. Indeed, at a first glance DHM shows promise in treating hangovers in some carefully controlled mouse experiments. In these experiments, researchers found that in mice that were given access to alcohol, DHM decreased the amount of alcohol they consumed and changed the GABA system so that it was not as activated by alcohol as it normally is15. This means that DHM might help prevent a GABA/glutamate imbalance during drinking, which you might recall scientists think could be a factor in causing hangovers. Scientists also found that DHM increased the breakdown of alcohol by enhancing the process covered in Figure 1, which resulted in less alcohol in the mice16. Although the scientists did not directly measure hangover symptoms, since DHM breaks down alcohol and its metabolites quicker, DHM could help prevent a hangover.

However, a major limitation of DHM is that it is really hard to get the chemical into the body through a pill format17. In animal experiments, DHM is injected directly into the animals, not given to animals through a pill. So, even though DHM is currently available to humans in a pill form, this likely means almost no DHM in hangover pills actually gets to be used by the body, essentially eliminating any potential benefit. As a final note about these pills, many are sold as “dietary supplements” since they contain naturally occurring ingredients. But this means that they aren’t regulated by the FDA and most of the currently available hangover products do not have any human data actually demonstrating their safety or effectiveness18. While these products might not immediately be harmful, rigorous studies have not been conducted, and in the case of DHM, likely very little of the drug in a pill format gets into the body. While drugs like DHM might one day be helpful, many more experiments are needed to evaluate them in humans and change the drugs in a way to make them more usable by our bodies.

Conclusion

With all the uncertainty surrounding hangovers, there is only one sure way to prevent them: abstinence. I’ve never woken up hungover after a night I didn’t drink alcohol. But with warmer weather, outside activities, and backyard BBQs on the horizon, many people likely won’t abandon alcohol entirely. So, this spring and summer, all you can do is drink responsibly, and be sure to watch your alcohol intake to avoid that dreaded hangover.

References

1. Swift, R. & Davidson, D. Alcohol hangover: mechanisms and mediators. Alcohol Health Res World 22, 54–60 (1998).

2. Palmer, E. et al. Alcohol Hangover: Underlying Biochemical, Inflammatory and Neurochemical Mechanisms. Alcohol and Alcoholism 54, 196–203 (2019).

3. Tsai, G., Gastfriend, D. & Coyle, J. The glutamatergic basis of human alcoholism. AJP 152, 332–340 (1995).

4. Rajendram, R., Rajendram, R. & Preedy, V. R. Acetaldehyde. in Neuropathology of Drug Addictions and Substance Misuse 552–562 (Elsevier, 2016). doi:10.1016/B978-0-12-800213-1.00051-1.

5. Brooks, P. J., Enoch, M.-A., Goldman, D., Li, T.-K. & Yokoyama, A. The Alcohol Flushing Response: An Unrecognized Risk Factor for Esophageal Cancer from Alcohol Consumption. PLoS Med 6, e1000050 (2009).

6. Ylikahri, R. H., Huttunen, M. O., Eriksson, C. J. P. & Nikklä, E. A. Metabolic Studies on the Pathogenesis of Hangover. Eur J Clin Investigation 4, 93–100 (1974).

7. Mackus, M. et al. The Role of Alcohol Metabolism in the Pathology of Alcohol Hangover. JCM 9, 3421 (2020).

8. Maxwell, C. R., Spangenberg, R. J., Hoek, J. B., Silberstein, S. D. & Oshinsky, M. L. Acetate Causes Alcohol Hangover Headache in Rats. PLoS ONE 5, e15963 (2010).

9. Diamond, S. M. & Henrich, W. L. Acetate Dialysate Versus Bicarbonate Dialysate: A Continuing Controversy. American Journal of Kidney Diseases 9, 3–11 (1987).

10. Doremus‐Fitzwater, T. L. et al. Intoxication‐ and Withdrawal‐Dependent Expression of Central and Peripheral Cytokines Following Initial Ethanol Exposure. Alcoholism Clin & Exp Res 38, 2186–2198 (2014).

11. González-Quintela, A. et al. INFLUENCE OF ACUTE ALCOHOL INTAKE AND ALCOHOL WITHDRAWAL ON CIRCULATING LEVELS OF IL-6, IL-8, IL-10 AND IL-12. Cytokine 12, 1437–1440 (2000).

12. Walter, T. J. & Crews, F. T. Microglial depletion alters the brain neuroimmune response to acute binge ethanol withdrawal. J Neuroinflammation 14, 86 (2017).

13. Penning, R., van Nuland, M., AL Fliervoet, L., Olivier, B. & C Verster, J. The pathology of alcohol hangover. Current Drug Abuse Reviews 3, 68–75 (2010).

14. Dihydromyricetin. in LiverTox: Clinical and Research Information on Drug-Induced Liver Injury (National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases, Bethesda (MD), 2012).

15. Shen, Y. et al. Dihydromyricetin As a Novel Anti-Alcohol Intoxication Medication. J. Neurosci. 32, 390–401 (2012).

16. Silva, J. et al. Dihydromyricetin Protects the Liver via Changes in Lipid Metabolism and Enhanced Ethanol Metabolism. Alcoholism Clin & Exp Res 44, 1046–1060 (2020).

17. Liu, L., Yin, X., Wang, X. & Li, X. Determination of dihydromyricetin in rat plasma by LC-MS/MS and its application to a pharmacokinetic study. Pharmaceutical Biology 55, 657–662 (2017).

18. Verster, J. C., Van Rossum, C. J. I. & Scholey, A. Unknown safety and efficacy of alcohol hangover treatments puts consumers at risk. Addictive Behaviors 122, 107029 (2021).

Cover photo by Michal Jarmoluk from Pixabay.

Figure 1 made with BioRender.com

Leave a comment