April 1st, 2025

Written by: Sophie Liebergall

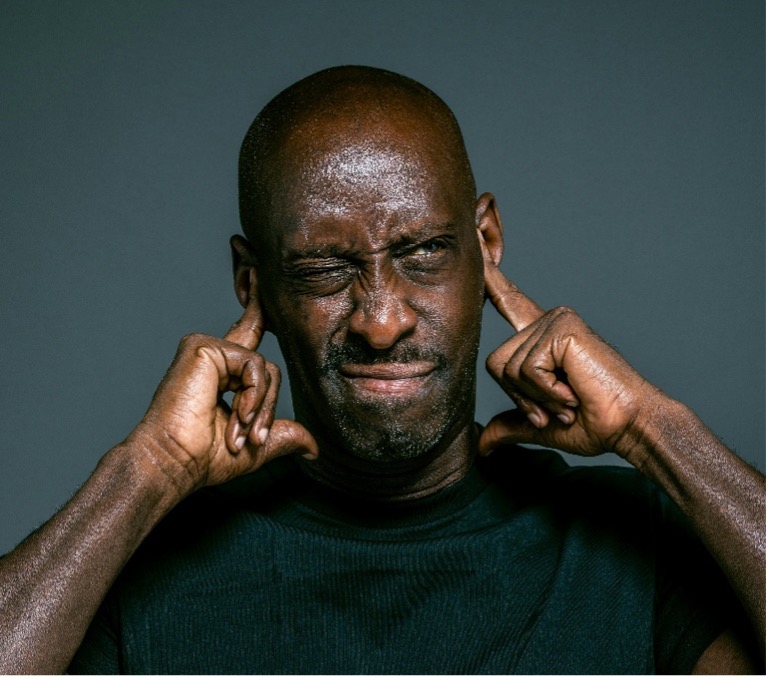

At some point in their lives, most people will have the experience of being suddenly struck by a ringing or buzzing sound. Though the sound feels very real, one generally figures out very quickly that it’s not being caused by something in the environment. This ringing sound, called tinnitus, is a reminder that the sensations we feel are created by our brain, whether it is responding to something in the outside world or not.

In most people, the ringing sound goes away in just a couple of seconds. But in about 15% of people, the ringing sound persists. These people with permanent ringing sounds have chronic tinnitus, a mysterious and often extremely distressing condition without any clear cause or cure. In this post, we’ll talk about what neuroscientists have learned about what is happening in the brain during the sensation of tinnitus, and how this knowledge could be used to develop new treatments that could free people from a constant ringing in their ears.

How does the brain create the sensation of a sound?

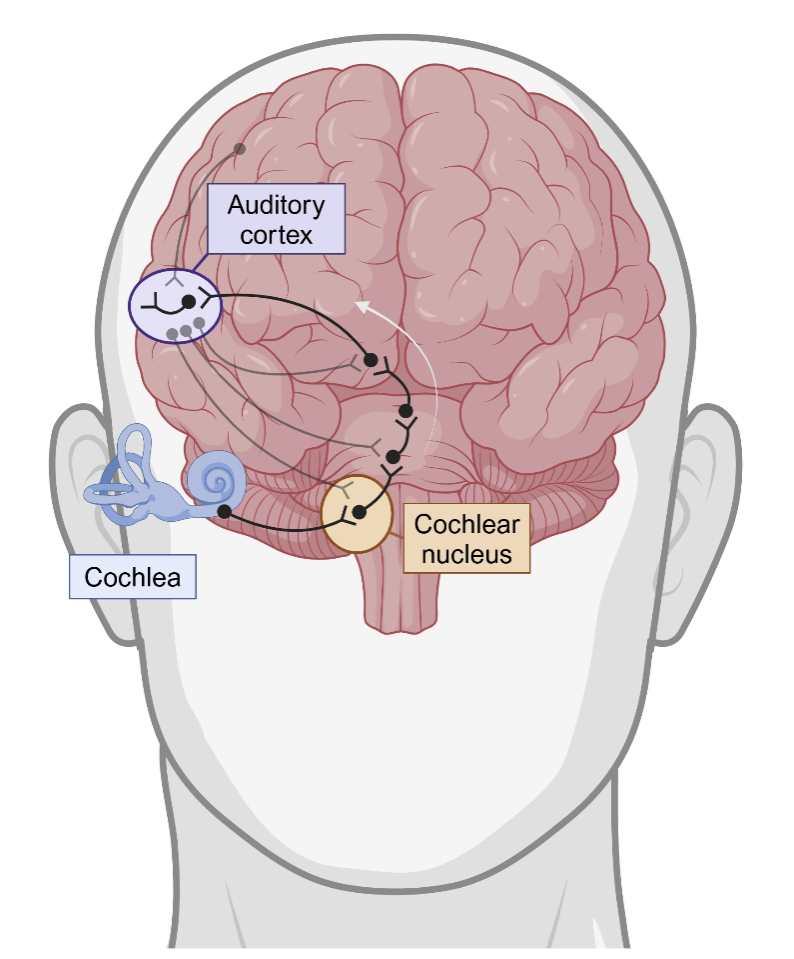

Before we can talk about what is happening in the brain during tinnitus, we first need to talk about how the brain turns sound waves into the experience of hearing a sound (Figure 1).1 When something produces sound waves in the environment, your ears funnel those sound waves onto a structure in your ear called the cochlea. The cochlea, whose name comes from the Latin word for snail shell because of its distinct spiral structure, has cells along this spiral that are activated by sound waves. These cells translate sound waves into electrical signals that the brain can understand. But these signals must pass through several waystations before they reach the part of the brain that creates the feeling of a sound. The first waystation is a part of the brainstem called the cochlear nucleus, which does some basic processing of the sound. The sound then passes through a few more waystations in the brain until it finally reaches the auditory cortex. It’s the cells in the auditory cortex who are responsible for creating the actual “feeling” of what it is to hear a sound.

There are two more factors to add to the picture of how the brain processes sound that affect our understanding of what goes wrong during tinnitus. The first is that sound processing isn’t just a simple one-way street from the cochlea to the auditory cortex. Sometimes signals can go backwards from the auditory cortex to earlier waystations. And sometimes other brain regions can send signals that modify how sound information travels up the pathway. For example, if you’re being chased by a bear, the fear regions of the brain can send signals that temporarily suppress distracting sound information from being passed up to the auditory cortex until you’ve reached safety.

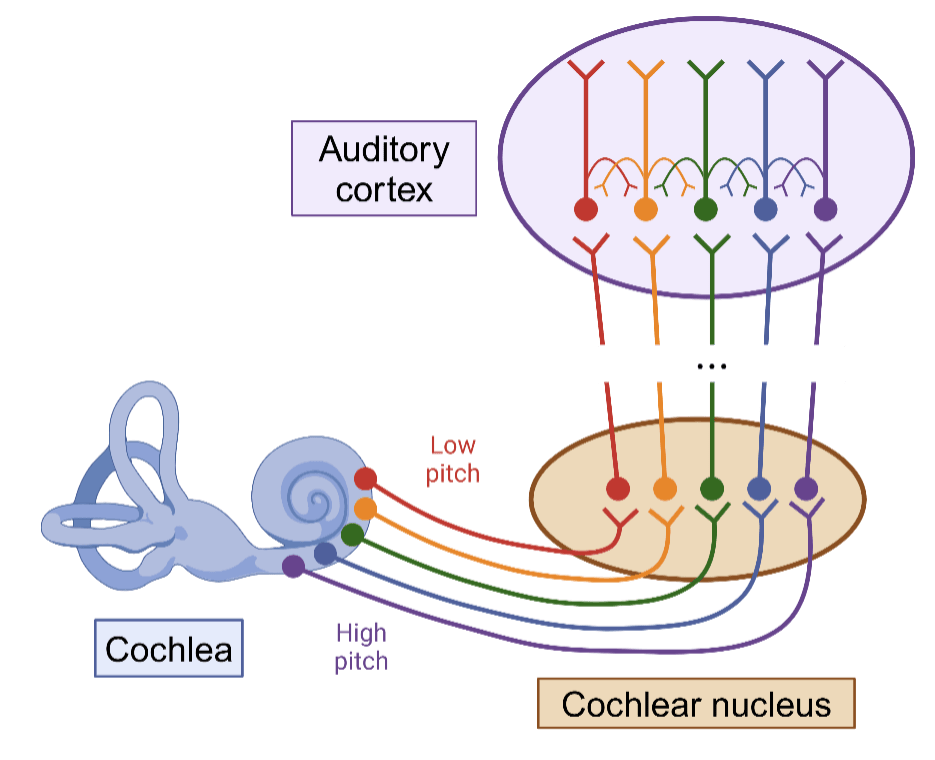

The second factor has to do with how high a low a sound is, or its pitch. Complex sounds like speech and music are usually a combination of many sound waves that have different pitches. To decode these complex sounds, the brain breaks them up into their different pitches (Figure 2). This division starts in the cochlea: cells closer to the base of the cochlea’s spiral process higher pitch sounds, whereas cells closer to the inside of the spiral process lower pitch sounds. And this division by pitch largely continues throughout the sound-processing pathway all the way to the auditory cortex.

Where does the ringing sound of tinnitus come from?

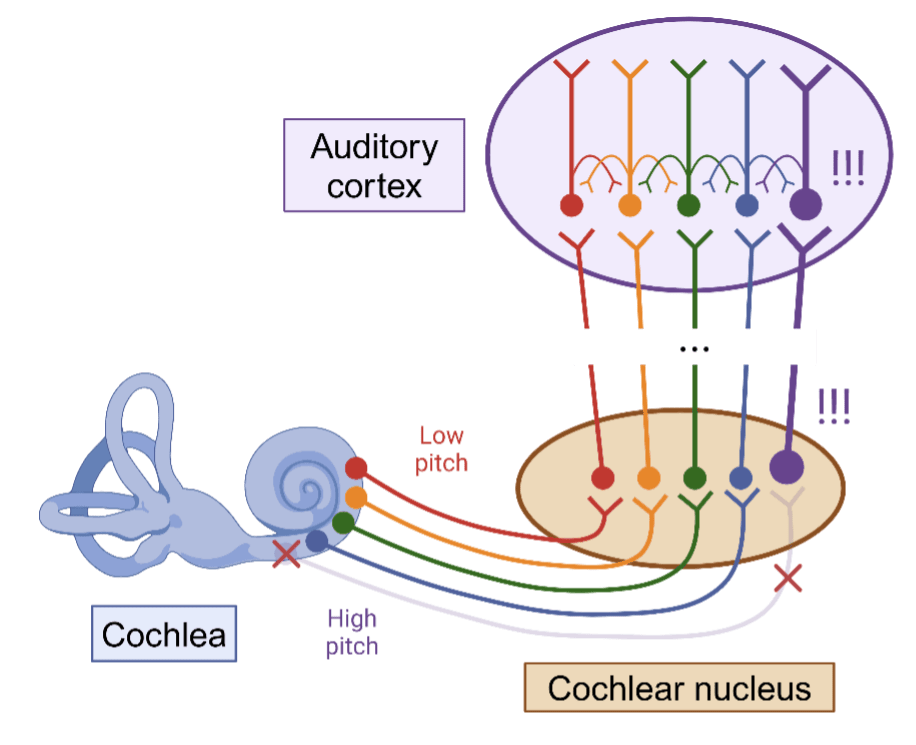

Even though we have a decent understanding of the ways in which the brain processes sounds, how exactly these mechanisms can be hijacked to produce chronic tinnitus has not yet been sorted out. Nevertheless, over the last few decades doctors and neuroscientists have been combining observations in patients with experiments performed in the lab to form theories about how changes in the brain cause tinnitus.2,3 The most important observation is that almost all patients who go on to develop chronic tinnitus already had some degree of hearing loss.4 These patients can have hearing loss for a number of reasons, but the most common causes are simply aging or exposure to loud noises. It’s somewhat counterintuitive that hearing loss would leads to hearing more sound in one’s head in the form of tinnitus. But because the association of tinnitus with hearing loss is so strong, researchers hypothesize that tinnitus is the result of brain circuits adapting to being fed less sound. This hyothesis is bolstered by additional observations about the pitch of the tinnitus. For most people that have hearing loss, their hearing loss is worse at certain pitches than other. (For the majority of people, hearing loss is most severe at te highest pitches because the high pitch cell in the cochlea are closest to its opening). Interestingly, many patients report that their tinnitus sounds like the exact frequency where their hearing loss is the worst.5

Because it’s both technically and ethically challenging to record signals from the brain of a living human, neuroscientists often must perform experiments in other animals, like mice. There are limitations, however, to studying tinnitus in non-human animals. Unlike humans, other animals can’t tell us what they’re hearing inside their head. Thus, scientists have had to get crafty to try to accurately recreate the ringing sound in animals so that they can record brain activity during tinnitus.

In one common method, scientists train a mouse to lick from a spout when a sound is played and to stop licking when it is silent. The scientists then expose the mouse to a loud sound or drug to give the mouse hearing loss. After giving the mouse’s brain a little time to adapt to the hearing loss, they then test the mouse on the lick task again. If the mouse starts to lick during times when they aren’t playing any sound, the researchers assume that the mouse is hearing a phantom sound akin to tinnitus.3

The most consistent finding in animal studies of tinnitus have shown that cells all throughout the sound processing pathway are more active than in control animals that don’t have tinnitus.2,3,6 Many scientists believe that the problem probably starts in the cochlear nucleus. When cochlear nucleus cells expect to receive signals from cochlea but instead hear silence, they try to turn the volume up and up (through tactics like changing the proteins in their membranes or strengthening their connections with other cells) (Figure 3). Eventually, they turn the volume knob up too high. This increase in activity is passed along the other brain regions in the pathway until it reaches the auditory cortex, where it directly causes the feeling of the ringing sound. Studies suggest that the increased activity causes additional changes in the auditory cortex itself, so that the tinnitus becomes maintained over time.

How can we save patients from the bells?

While unfortunately there is no cure for tinnitus, many patients can get significant relief from the psychological stress of hearing constant ringing with tools like sound therapy, sound amplification with hearing aids, and cognitive behavioral therapy. There are also several potential new therapies on the horizon that may offer patients hope for freedom from the sound. One potential therapeutic approach is to use electrical stimulation. Electrical stimulation is thought to work by paradoxically decreasing the activity of cells.7 Thus, it is a very effective treatment for other diseases that are associated with too much activity in a certain part of the brain, such as Parkinson’s disease and epilepsy. There are currently clinical trials for electrical stimulation devices that are implanted at the different waystations along the sound-processing pathway.6 Another potential treatment is a drug called RL-81, which has shown promising preliminary results in mice.8 This drug directly targets a protein in the membrane of cells in the cochlear nucleus. When the drug activates the protein, it quiets down their activity, thus stopping the ringing sound at its source.

Though we still have a long way to go in understanding its causes and mechanism, chronic tinnitus reveals the complexity of translating sound waves from the environment into the feeling of sound in one’s head. Hopefully an improved understanding of the neurobiology of tinnitus can lay the foundation for a new generation of therapies so that patients can hear more of the sounds that they want to hear, and fewer of the sounds that they don’t.

References

1. Auditory pathways: anatomy and physiology. in Handbook of Clinical Neurology vol. 129 3–25 (Elsevier, 2015).

2. Roberts, L. E. et al. Ringing Ears: The Neuroscience of Tinnitus. J Neurosci 30, 14972–14979 (2010).

3. Henton, A. & Tzounopoulos, T. What’s the buzz? The neuroscience and the treatment of tinnitus. Physiological Reviews 101, 1609–1632 (2021).

4. What Is Tinnitus? — Causes and Treatment | NIDCD. https://www.nidcd.nih.gov/health/tinnitus (2023).

5. Norena, A., Micheyl, C., Chéry-Croze, S. & Collet, L. Psychoacoustic Characterization of the Tinnitus Spectrum: Implications for the Underlying Mechanisms of Tinnitus. Audiology and Neurotology 7, 358–369 (2002).

6. Park, K. W., Kullar, P., Malhotra, C. & Stankovic, K. M. Current and Emerging Therapies for Chronic Subjective Tinnitus. J Clin Med 12, 6555 (2023).

7. Agnesi, F., Johnson, M. D. & Vitek, J. L. Chapter 4 – Deep brain stimulation: how does it work? in Handbook of Clinical Neurology (eds. Lozano, A. M. & Hallett, M.) vol. 116 39–54 (Elsevier, 2013).

8. Marinos, L. et al. Transient Delivery of a KCNQ2/3-Specific Channel Activator 1 Week After Noise Trauma Mitigates Noise-Induced Tinnitus. J Assoc Res Otolaryngol 22, 127–139 (2021).

Cover photo by Ketut Subiyanto, Pexels

Figures 1-3: Created using biorender.com by Sophie Liebergall.