Written by: Nita Rome

What are the things that motivate you? What makes you attend a boring meeting at work, do your taxes, or even take out the trash? Is it to get that promotion? Fear of the IRS? Not wanting your house to get stinky? When confronted with something we don’t want to do, we often still do it to gain or avoid something else.

But how about hobbies – why might someone engage in those? Most likely, it’s not because it makes them money. In fact, people often spend money to do said hobby. Some will even endure physical pain for their hobbies, like rock climbing or boxing. So why do it? Well, for fun!

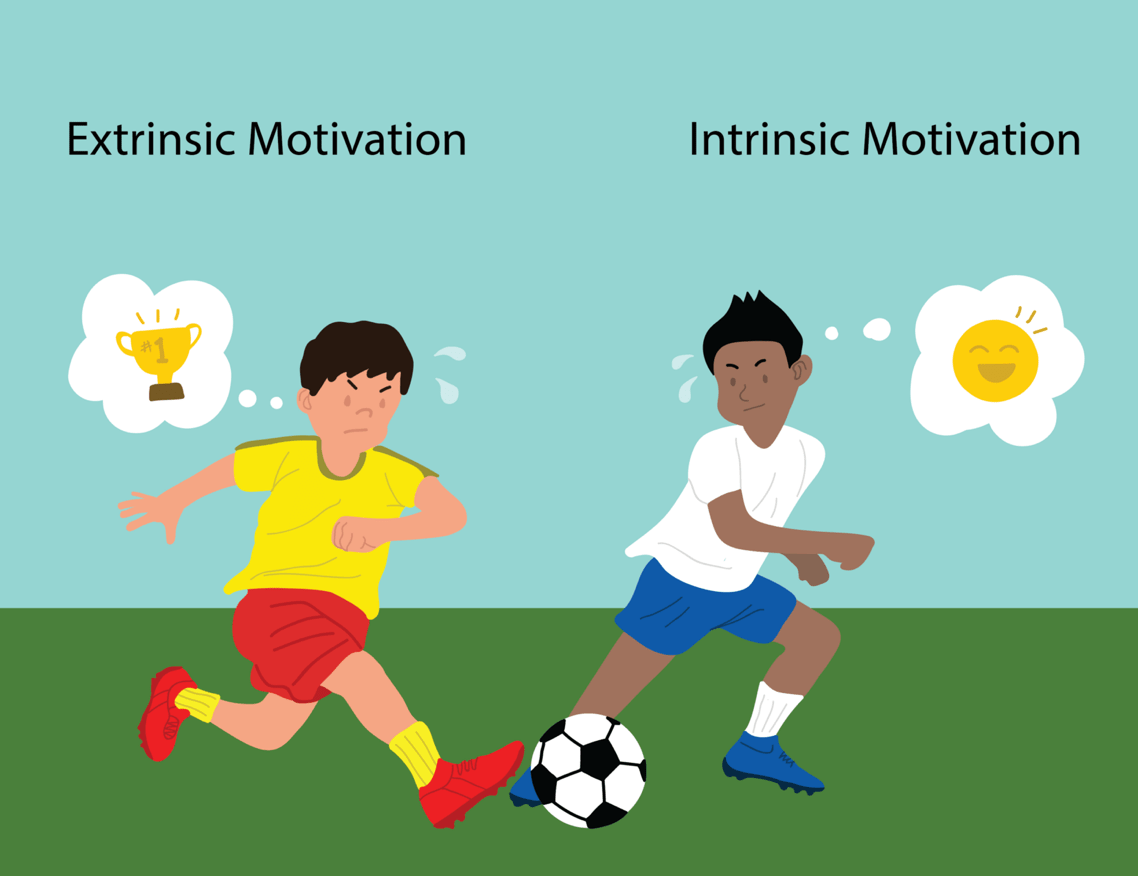

Motivation is not uniform. Different people will even have different motivations for the same action. If you look at the image at the top of this article, you can see that while both children are playing soccer, they are doing so for different reasons. The child on the left is focused on winning and getting that trophy, whereas the one on the right is just having fun. If you think about this and the examples discussed above, you can perhaps see a divide forming: some things we do because of outside forces, whereas others we do just for the sake of doing them.

Extrinsic and Intrinsic Motivations

According to a psychological framework called Self Determination Theory, motivation can fall into two broad categories: extrinsic and intrinsic. Extrinsic Motivation, as the name suggests, comes from a source outside or separate from the action being performed. For example, if someone, let’s call him John, sees that there is a local foot race next week and registration for the race is open. At first, John has no interest in participating, but after learning that there is a cash prize for the winner, he signs up. Here, John’s motivations for entering the race are entirely extrinsic, as the possibility of getting a reward is what pushed him to join the race. Money, fame, and praise are some other common extrinsic motivators.

Intrinsic motivation, on the other hand, comes from performing the action itself. Let’s say there is a second person, Julia, who hasn’t heard about the cash prize, but she likes to run and enjoys competition for its own sake, so she decides to enter the race as well. Julia’s motivations are intrinsic, as she is motivated by the act of running the race, not the prospect of getting a prize afterward. Other intrinsic motivators include curiosity, fun, or a sense of accomplishment.

Interplay Between Motivations

Not all motivations fall neatly into one category or the other. For many people, their profession is not only a source of income, but also something they enjoy doing, and therefore their reasons for going to work each day are not entirely intrinsically or extrinsically motivated. Consider the authors for PennNeuroKnow. I would venture that many of the NGG graduate students who write these articles decided to join a Neuroscience PhD program not only to advance their careers, but also because they enjoy studying the brain (because the brain is cool, duh).

So in some cases, like a job or education, it can be good to have that mix of intrinsic and extrinsic motivation. However, if a task is intrinsically motivating on its own, and then you add extrinsic rewards into the mix, such as money, that task can lose some of its initial intrinsic motivation. In other words, it can become less about fun, and more about the money.

Or, let’s say there is a child who loves to read, but as they get older, and more and more reading is assigned in school, the act of reading begins to feel more like a chore rather than a fun activity. As a result, they stop reading books in their free time. While that child is still motivated to read, this motivation now stems from wanting to get good grades (extrinsic) rather than the enjoyment of getting lost in a book (intrinsic). Other outside factors, such as negative feedback,2 punishment, orders, and deadlines 3 can also reduce someone’s intrinsic motivation to perform a task.1

Why is this the case? Well perhaps in some ways we all have a little moody teenager inside of us who doesn’t want to do something specifically because our parents told us we have to (“I was planning on cleaning my room until you told me to, Mom!”). Some psychological theorists believe such mandates and restrictions may result in a decreased sense of autonomy, or independence, which, according to Self Determination Theory, is one of the central psychological needs for mental wellness. Evidence in support of this theory shows that situations that foster a sense of autonomy- those that create opportunities for individuals to choose and have control- can in turn promote intrinsic motivation, and possibly improve task performance and learning.4

It’s Always About Balance

Of course, this is not to say that all extrinsic motivations are inherently worth less, or that all rules and restrictions are bad. On the contrary, if we only ever did what we felt like doing, society could not function, and life would get very uncomfortable very quickly (think of all the trash that would pile up in your house – eww).

As with almost everything in life, the key is balance. Do the things you have to do, but also do some things just for fun. If you are a parent, teacher, or in a position of power, I’d suggest working to foster environments that allow for autonomy and choice, which in turn can foster curiosity and enjoyment.1 After all, when people have the freedom to explore and engage on their own terms, they are more likely to thrive.

Want to learn more about intrinsic and extrinsic motivation? Try these videos:

Short Video about Intrinsic and Extrinsic Motivation

Slightly Longer Video about Self Determination Theory and the Spectrum of Motivation

References

- Ryan, R. M. & Deci, E. L. Intrinsic and Extrinsic Motivations: Classic Definitions and New Directions. Contemp. Educ. Psychol. 25, 54–67 (2000).

- Deci, E. L. & Cascio, W. F. Changes in Intrinsic Motivation as a Function of Negative Feedback and Threats. https://eric.ed.gov/?id=ED063558 (1972).

- Amabile, T. M., DeJong, W. & Lepper, M. R. Effects of externally imposed deadlines on subsequent intrinsic motivation. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 34, 92–98 (1976).

- Zuckerman, M., Porac, J., Lathin, D. & Deci, E. L. On the importance of self-determination for intrinsically-motivated behavior. Pers. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 4, 443–446 (1978).

Cover Photo by Muhammad M Rahman, Wikimedia Commons