December 17th, 2024

Written by: Abby Lieberman

We often hear about tragedies that have occurred in cults; Jim Jones convinced over 900 people to commit suicide by drinking cyanide-laced Kool-Aid. Charles Manson directed his followers to commit horrific murders. Marshall Applewhite led 39 people to join a mass suicide under the belief that their souls would ascend to an alien spacecraft. How are cult leaders able to manipulate their followers into committing such terrible acts? The answer lies in a psychological manipulation technique called brainwashing.

What is brainwashing?

Brainwashing is a method used to persuade someone to adopt certain beliefs, loyalties, and behaviors, often against their own will or knowledge1. The process of brainwashing someone typically involves manipulating their surroundings and social connections so that they will adopt new beliefs and break their ties to opposing groups or ideas. But what happens in the brain of someone being brainwashed?

Step One: Enhancing vulnerability through social Isolation

When someone is inducted into a cult, they are often required to make drastic changes to their appearance, diet, sleep schedule, and social behaviors. These requirements often lead to stress, confusion, exhaustion, and fear, which makes the person more vulnerable to manipulation. The individual is effectively removed from a familiar environment and is cut off from external support and perspectives that differ from those of the cult. This leads to a sense of disconnection and social isolation from the outside world2.

Social isolation is known to induce long-lasting stress in both humans and animals, and has a profound effect on the brain. Specifically, social isolation leads to changes in the structure and function of key brain regions3, including the prefrontal cortex (a region responsible for critical thinking and decision making), the amygdala (a center for fear processing), and the hippocampus (a region responsible for memory) (Figure 1).

Some studies show that isolation leads to a decrease in prefrontal cortex volume, and in juvenile mice, leads to a decrease in communication between neurons in the prefrontal cortex and other parts of the brain3. These changes likely contribute to the impaired decision making and critical thinking seen in brainwashed people. When people and animals are isolated, the amygdala becomes overly active, which can reinforce feelings of fear and anxiety. Long term isolation during the COVID-19 pandemic led to an increase in amygdala size among adult study participants. Notably, these changes went away when the pandemic lockdown ended and normal social interaction resumed4. In a study examining the brains of people who had participated in long arctic expeditions5, researchers found that parts of their hippocampus had shrunk significantly. Lastly, social isolation is known to lead to an increase in overall “brain age”, which is associated with poor mental and physical health outcomes6. Once a victim of brainwashing is isolated and in a vulnerable emotional state, cults tightly control what the person hears, sees, and experiences; the world of the victim is effectively shrunk, and they are forced to interpret their reality solely through the lens of the cult’s beliefs.

Step Two: Building new behaviors and brain pathways through operant conditioning

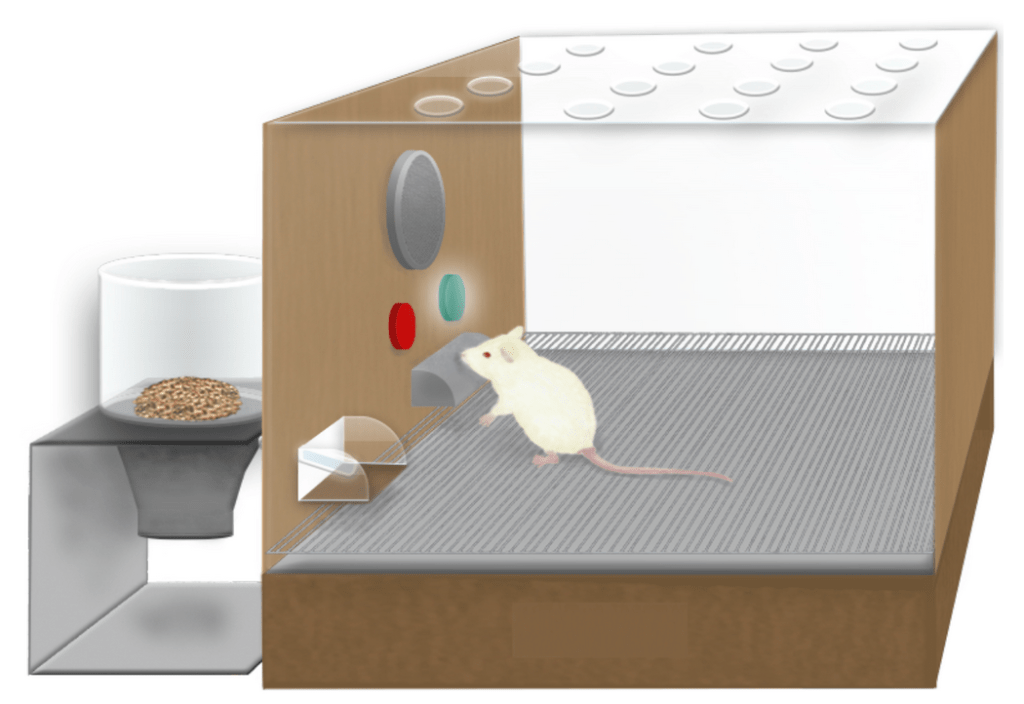

In order to maintain control of their followers, cult leaders need to reinforce the beliefs of the cult repeatedly. To do this, cults often use a tool called operant conditioning that is borrowed from classic animal behavior studies7. Operant conditioning was developed in the mid-20th century by B.F. Skinner, and is a method of learning that uses rewards and punishments to teach someone to increase or decrease a specific behavior. To understand operant conditioning, imagine a mouse in a small chamber with a green light, a red light, a lever, and a dispenser filled with (delicious!) cookies. Initially, the mouse explores the chamber without understanding the connection between the lever, the light, and the cookie dispenser. The mouse is gradually taught to associate pressing the lever with receiving a cookie. This process often involves shaping, where any action close to the desired behavior—such as moving toward the lever—is rewarded to encourage further interaction. Eventually, the green light is introduced as a cue. When the light turns on, it indicates to the mouse that pressing the lever will now release a cookie (Figure 2). The mouse learns to associate the green light with the opportunity for a reward, and will increase lever pressing when the green light is on.

Cults similarly use operant conditioning to train their victims and maintain a brainwashed state. Rule-following or participation in cult activities are consistently rewarded with praise, affection, or privileges. For example, individuals who follow the group’s rules may receive social approval or inclusion in group activities, reinforcing the behavior. Conversely, punishments like isolation, verbal abuse, or withholding privileges are used to discourage questioning or disagreement with the cult’s beliefs.. Over time, this trains individuals to associate rule-following with safety and acceptance, while linking independent thought with fear, guilt, or exclusion.

The brain regions involved in operant conditioning include the dopaminergic system, and particularly a cluster of brain regions called the basal ganglia, which are critical for reinforcing behaviors and consequently forming habits8. Positive reinforcement, like praise or affection, activates dopamine pathways, reinforcing the behaviors that led to the reward. The prefrontal cortex, responsible for decision-making and evaluating consequences9, becomes involved in assessing whether following the rules or challenging them is more advantageous. In cases of punishment, the amygdala, as mentioned before, heightens the victim’s sensitivity to the negative consequences of disobedience, causing fear and guilt to deter them from future disobedience. Through these mechanisms, operant conditioning not only shapes behavior but also restructures brain activity, reinforcing the victim’s reliance on the cult’s rules and suppressing independent thought.

Dealing with the aftermath of brainwashing

Brainwashing is like rewiring the brain to dance to someone else’s tune, turning independent thoughts into programmed responses. But here’s the hopeful twist: just as the brain can be reshaped through operant conditioning, it can also heal and rebuild through positive experiences, supportive environments, and the reintroduction of critical thinking—a process known as deprogramming10. This involves gently challenging the imposed beliefs, fostering connections with trusted people outside the manipulative environment, and creating space for personal reflection and rediscovery. Over time, the brain’s natural resilience helps individuals regain autonomy, rediscover their identity, and reclaim their ability to think freely and critically.

References

- The Editors of Encyclopedia Britannica. (2013). Brainwashing. In Encyclopædia Britannica. https://www.britannica.com/topic/brainwashing

- Baron, R. S. (2000). Arousal, Capacity, and Intense Indoctrination. Personality and Social Psychology Review, 4(3), 238-254.

- Xiong, Y., Hong, H., Liu, C. et al. (2023). Social isolation and the brain: effects and mechanisms. Mol Psychiatry 28, 191–201.

- Salomon, T., Cohen, A., Barazany, D., Ben-Zvi, G., Botvinik-Nezer, R., Gera, R., Oren, S., Roll, D., Rozic, G., Saliy, A., Tik, N., Tsarfati, G., Tavor, I., Schonberg, T., & Assaf, Y. (2021). Brain volumetric changes in the general population following the COVID-19 outbreak and lockdown. NeuroImage, 239, 118311.

- Stahn, A. C., Gunga, H.-C., Kohlberg, E., Gallinat, J., Dinges, D. F., & Kühn, S. (2019). Brain Changes in Response to Long Antarctic Expeditions. New England Journal of Medicine, 381(23), 2273–2275.

- Lay-Yee, R., Hariri, A. R., Knodt, A. R., Barrett-Young, A., Matthews, T., & Milne, B. J. (2023). Social isolation from childhood to mid-adulthood: is there an association with older brain age?. Psychological medicine, 53(16), 7874–7882.

- Staddon, J. E., & Cerutti, D. T. (2003). Operant conditioning. Annual review of psychology, 54, 115–144.

- Seger, C. A., & Spiering, B. J. (2011). A critical review of habit learning and the Basal Ganglia. Frontiers in systems neuroscience, 5, 66.

- Friedman, N.P., Robbins, T.W. (2022). The role of prefrontal cortex in cognitive control and executive function. Neuropsychopharmacol. 47, 72–89.

- Ungerleider, J. T., & Wellisch, D. K. (1979). Coercive persuasion (brainwashing), religious cults, and deprogramming. The American journal of psychiatry, 136(3), 279–282.

Cover photo by Poldavia on Wikimedia Commons.

Figure 1 by Begoon on Wikimedia Commons. Adapted by Abby Lieberman.

Figure 2 by Togopic on Wikimedia Commons.

Leave a comment