December 11th, 2024

Written by: Joseph Gallegos

Humans may form impressively complex social structures, but ants make the planet-wide contest closer than you’d think. There are over 14,000 known species of ants, and they are estimated to make up a whopping 15-20% of all land-dwelling animals 1. Ants’ far-reaching success may be due in part to their unique social structure. In contrast to many species where individuals compete with each other to survive, ants instead have developed their own self-sustaining societies called colonies, where the work of each individual ant benefits the whole. This arrangement requires individual ants within a colony to be ‘assigned’ a job, where their behavior becomes specialized to perform the specific jobs they are tasked with. From gathering food, to nurturing their young, to mating and reproducing, ants have developed specialized social classes to ensure their colonies run efficiently. How this complicated social arrangement is produced at the levels of brain function and behavior has puzzled biologists for decades. But advances in technology and renewed interest in tackling this question is beginning to bridge the gap between the brain and behavior.

How differences in the brain can sculpt ant societies

Ant society is structured very differently from humans and most other categories of animal life on the planet. Ants are matriarchal, meaning that they are ‘governed’ by a female class. In fact, the next time you find yourself staring at a line of ants trudging through the grass, every single ant that you see is probably female. Male-sexed ants do exist, but they are usually only present for a short amount of time, and are only kept around long enough to produce the next generation.

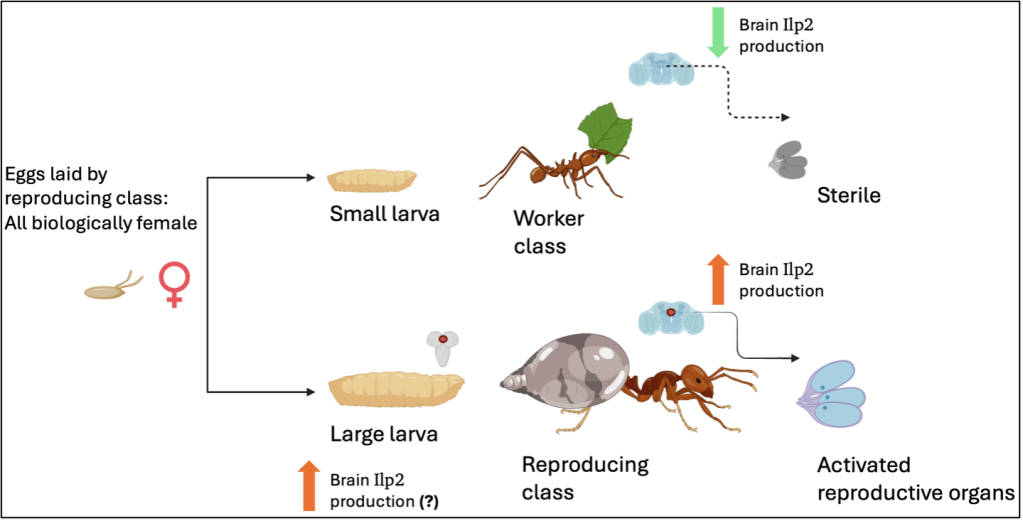

Although there are many different jobs within a colony, the most obvious place where work has been divided into clear-cut social classes is when it comes to reproduction. As indicated above, within an ant colony all ants are biologically female, however the ability to reproduce is reserved to a select few. Some ants will develop fully functioning reproductive systems, and will therefore be assigned to be part of the reproductive class. All the rest are effectively sterile, and will instead become non-reproducing worker ants 2,3. To unravel how this division of labor is produced, scientists examined how the brains of reproductive vs. nonreproductive ants might be different.

In a recent study, researchers compared the types of signals produced by the brains of reproductive ants and nonreproductive ants 6. They found that the brains of reproducing ants generated higher levels of a compound called insulin-like peptide 2 (Ilp2). The researchers went on to find that Ilp2 was being produced by a specific region of the brain, suggesting that there is a brain center dedicated to the release of Ilp2.

To determine if the difference in Ilp2 production between nonreproductive ants and reproducing ants was driving their social roles, the scientists examined how the amount of Ilp2 changed in response to different conditions. One species of ant that they studied, called Ooceraea biroi, alternate between cycles of reproducing and non-reproducing behaviors within their colony instead of having a single reproducing queen. They are known to be able to ‘switch off’ their reproductive cycles when new larvae are born and instead switch to a ‘caretaker’ role and take care of their offspring. The scientists tested the idea that Ilp2 determines an ant’s social role by looking at whether the amount of Ilp2 changes in as they make this transition. When ants were actively reproducing, levels of Ilp2 were high, but when they switched to caretaker roles Ilp2 levels in the brain decreased 6. Intriguingly, if scientists experimentally added Ilp2 into the typically sterile worker ants, they saw an immediate activation of their reproductive organs, indicating that Ilp2 production is directly contributing to the dramatic changes in ant social roles.

This increase in Ilp2 levels in the brains of reproductive ants was observed in all different ant species researchers examined. This finding suggests that increased Ilp2 release from the brain might be a universal system that ants developed, resulting in this division of reproductive behavior in all varieties of ant species.

How might differences in ant brain function originate

This study revealed that the split-up of ants into distinct social roles can be driven by changes in brain signaling. But how do these differences in Ilp2 generation within the brain arise? While scientists are still not certain, the answers likely lie in the way that ant larvae develop.

One thing ant biologists have found is that the ‘job’ that an ant receives in its life is entirely based on how big they are as babies 2,3. In all species of ant, larva that gain large body mass will always become part of the reproducing class, and smaller larva will always become non-reproducing workers (Figure 1) 2. This observation suggests that the forces that shift the behavior and bodily functions of ant occur as they are maturing, and are sensitive to the nutritional status of the larva. Similar to how insulin in humans is released into our blood as a message to indicate we have just eaten a lot of food, Ilp2 and related signaling hormones in insects increase in response to eating and nutrient intake in the larva as they develop 7. Scientists believe that ants may have adapted Ilp2 signaling from the brain to serve two purposes: a signal for high nutrient availability when they were young, and a driver of reproductive function as they mature (Figure 1) 6.

Since producing offspring requires a significant investment of precious nutritional resources, it makes sense that ants would develop a system that entrusts their reproductive fates with how good the eating was when they were babies. And this begins to paint a holistic picture of how simple changes in brain signaling emerged to create this division of social roles seen in ants. However, it is important to note that this is only a theory and there is still a lot of experimental work that would need to be done to test and prove this.

The potential of ants in neuroscience research

How complex social behaviors develop has been a question scientists have wondered for a long time, and it is becoming clearer to brain researchers that ants are teeming with potential to help answer that question 5. Ants offer the perspective that complicated behaviors and social roles can develop from relatively simple changes of the brain even in genetically similar ants. The highlighted study identified brain signals like Ilp2 as being important to promote the divergence of reproductive ants and worker ants, but there are still many more fascinating things to be learned. How do worker ants become further divided into foragers, or soldiers, or babysitters 8,9? There are still many interesting questions about the unique social prowess of ants that biologists and any keen observer have been fascinated by for a long time. And with recent advances in neuroscience technology, and renewed interest in studying the behavior of ants, there are sure to be many more exciting discoveries in the near future.

References

1. Wilson EO, Nowak MA. Natural selection drives the evolution of ant life cycles. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2014;111(35):12585-12590. doi:10.1073/pnas.1405550111

2. Trible W, Kronauer DJC. Caste development and evolution in ants: it’s all about size. Levine JD, Kronauer DJC, Dickinson MH, eds. J Exp Biol. 2017;220(1):53-62. doi:10.1242/jeb.145292

3. Trible W, Kronauer DJC. Hourglass Model for Developmental Evolution of Ant Castes. Trends Ecol Evol. 2021;36(2):100-103. doi:10.1016/j.tree.2020.11.010

4. Godfrey RK, Swartzlander M, Gronenberg W. Allometric analysis of brain cell number in Hymenoptera suggests ant brains diverge from general trends. Proc R Soc B Biol Sci. 2021;288(1947):20210199. doi:10.1098/rspb.2021.0199

5. Frank DD, Kronauer DJC. The Budding Neuroscience of Ant Social Behavior. Annu Rev Neurosci. 2024;47(1):167-185. doi:10.1146/annurev-neuro-083023-102101

6. Chandra V, Fetter-Pruneda I, Oxley PR, et al. Social regulation of insulin signaling and the evolution of eusociality in ants. Science. 2018;361(6400):398-402. doi:10.1126/science.aar5723

7. Toth AL, Robinson GE. Evo-devo and the evolution of social behavior. Trends Genet. 2007;23(7):334-341. doi:10.1016/j.tig.2007.05.001

8. Ju L, Glastad KM, Sheng L, et al. Hormonal gatekeeping via the blood-brain barrier governs caste-specific behavior in ants. Cell. 2023;186(20):4289-4309.e23. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2023.08.002

9. Gospocic J, Shields EJ, Glastad KM, et al. The Neuropeptide Corazonin Controls Social Behavior and Caste Identity in Ants. Cell. 2017;170(4):748-759.e12. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2017.07.014

Cover photo by diego_torres on Pixabay

Figure 1 generated by Joseph Gallegos using biorender

Leave a comment