November 12th, 2024

Written by: Stephen Wisser

Today marks exactly one week from the American 2024 presidential election. Over the last several months, candidates have spent billions of dollars and lots of time trying to convince Americans to vote for them…but was that really necessary? All the talk about policy, moral character, and who is best “fit to serve” was a strategy meant to appeal to a so called “rational voter”, that is someone who thinks about complex issues and positions and then makes an informed choice. But as we know, people aren’t always rational. How and why does a voter make decisions that ignore important information like policy stances? The answer, as we’ll explore in this post, may be partly due to a variety of ancient patterns of decision making and psychological biases that have nothing to do with rational arguments or stances. To be clear, this post is not meant to endorse any candidate or make any political commentary, it is just a discussion of biases that may influence voting on both sides of the aisle. Let’s explore what neuroscience can teach us about how people really make decisions about voting.

Voting for a Face

Explaining how we make decisions is a difficult task since making decisions is a complex process. One theory on how we make decisions is called ecological rationality1. This theory claims that we make decisions prioritizing “problems confronted earlier in evolution”2. This means that when faced with a decision, our brains are wired to consider basic or simple needs first like seeking food or finding shelter. Although there are many things to consider when making decisions, ecological rationality suggests we can often ignore a lot of that information and make a simple decision with only a few facts1, prioritizing basic necessities of life like our early ancestors did. One simple fact we often prioritize is what we see. If an angry dog starts chasing you down the sidewalk, you don’t think about all available options of where to run and what is the best and safest choice. You likely just start running based on a dangerous scene you see! It turns out even in non-dangerous situations, simple visual information gets priority in decision making, which plays into the physical appearance of political candidates. Scientists have shown that people can accurately predict election outcomes based on very short glimpses of candidate photos, even when they know nothing about them or are politicians from another country3,4. Preschoolers, who likely don’t have concrete political stances, can predict who will win an election just by looking at pictures5. These studies suggest that without any additional information, people get the impression that someone is competent or a strong leader from visual appearance alone, but how does that happen? What does the brain look for to give a quick gut impression that someone is competent or likely to be a good leader?

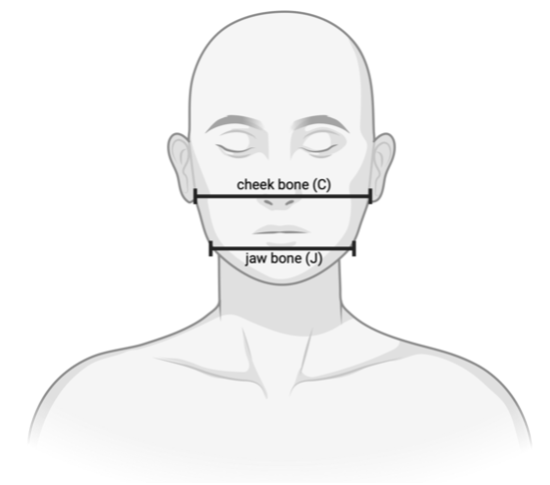

In a series of recent experiments, scientists studied how monkeys looked at pictures of political candidates to try to answer this very question2. The scientists found that when presented with pictures of human political candidates, monkeys generally looked more at the candidates who lost2. When presented with images of monkey faces, monkeys spend more time looking at subordinate or “lesser” monkeys6,7 since eye contact is seen as a sign of aggression2,8. This suggests that there must be some dominant feature about the winning candidate that made the monkeys want to look away. Out of several facial features, the researchers found that a measurement called jaw prominence seemed to influence how long the monkeys looked at a candidate2. Jaw prominence essentially means that the jawbone is wider compared to the cheek bone (Figure 1). A more defined or prominent jaw bone seems to give a more dominant impression, since monkeys looked less at candidates with a higher jaw prominence2. Not surprisingly, jaw prominence also appeared to influence the real election results2 suggesting that like monkeys, humans might have a visual bias toward perceiving candidates with a more pronounced jaw bone as stronger and a better leader. It is important to note that the monkeys’ gaze bias was a small effect, and monkeys are not humans. While interesting, as with all experiments involving animal models, we should take this experiment with a grain of salt.

Media bias

In addition to the idea that voters might subconsciously consider physical appearance of a candidate, media might shape people’s thoughts and voting decisions. In a previous post, this blog explored the idea that the environment you live in can help shape who you become. It turns out that the media you are exposed to, which is part of your environment, might also nurture your political and voting decisions regardless of party affiliation. In one study, researchers analyzed how the 1996 introduction of a new (at the time) Republican-leaning media, Fox News, influenced voting patterns in the 2000 election. This election was the first where Fox News was made available in some homes9, so it provided a unique opportunity to see how a new media can influence voting. The researchers found that there were 0.4 to 0.7% more Republican presidential votes in the towns that had access to Fox News compared to the towns where Fox News was not yet available9. That might not sound like a lot, but the researchers estimated that an increase of that size was roughly equivalent to 200,000 more Republican votes9 and in some senate races for this past election, decisions were made by only a few tens of thousands of votes. Importantly, this so called “Fox News Effect” applied to both Republican & Democratic voters9, suggesting that even some Democrats were nonetheless influenced by exposure to a Republican TV network. Perhaps most interesting of all however, the researchers found that access to Fox News seemed to increase Republican vote share for senate races as well, despite these races and candidates not being directly discussed on Fox News shows9. This suggests that the media itself might have been able to instill more underlying and general Republican political beliefs, and not just impressions of individual candidates. Although this was not a carefully-controlled experiment, this study shows that the media one is exposed to is worth considering as yet another factor that might be able to sway people’s voting beliefs.

The Bandwagon Effect & Polling

The final psychological factor to consider in our discussion is the bandwagon effect, the idea that people are more likely to agree with what other people are doing. In the context of politics, researchers believe that the bandwagon effect comes into play regarding polls10,11. In a recent carefully-controlled experiment12, participants were told to vote for a partisan organization (National Rifle Organization and Greenpeace for example) in a variety of issues like firearms and the environment. Before casting their votes, some participants were shown a poll regarding people’s voting behavior about the organizations. Compared to participants who were not shown the poll, participants who did see the poll tended to vote in line with the poll results they saw12, suggesting a clear bandwagon effect. Importantly, this bandwagon effect is also seen in European countries13 who have a different political system. This further suggests that the bandwagon effect may be a universal bias shared by all humans regardless of political system or environment. This makes sense if we remember the theory of ecological rationality because it is simpler to follow a group that has already made a decision (and hopefully thought through it!), than for you to do the hard work of making that decision yourself. Although polls are meant to get a feel for people’s opinions on candidates and issues, psychology would suggest they might actually influence those opinions!

Conclusion

When we decide how to cast our votes, there are a lot of political issues to consider. As we’ve seen in this post, the water is even cloudier since there might be several biases at play too. It will likely by impossible to “explain” this year’s election results and conclude whether any of the biases discussed here influenced the election. But next time you go to the voting booth, do your own experiment and stop to consider how any of these biases might be influencing your ballot.

References

1. Todd PM, Gigerenzer G, eds. Ecological Rationality: Intelligence in the World. Oxford University Press; 2012.

2. Jiang Y, Huttunen A, Belkaya N, Platt ML. Monkeys Predict US Elections. Published online September 19, 2024. doi:10.1101/2024.09.17.613526

3. Lawson C, Lenz GS, Baker A, Myers M. Looking Like a Winner: Candidate Appearance and Electoral Success in New Democracies. World Pol. 2010;62(4):561-593. doi:10.1017/S0043887110000195

4. Poutvaara P, Jordahl H, Berggren N. Faces of politicians: Babyfacedness predicts inferred competence but not electoral success. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology. 2009;45(5):1132-1135. doi:10.1016/j.jesp.2009.06.007

5. Antonakis J, Dalgas O. Predicting Elections: Child’s Play! Science. 2009;323(5918):1183-1183. doi:10.1126/science.1167748

6. Ebitz RB, Watson KK, Platt ML. Oxytocin blunts social vigilance in the rhesus macaque. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2013;110(28):11630-11635. doi:10.1073/pnas.1305230110

7. Jiang Y, Sheng F, Belkaya N, Platt ML. Oxytocin and testosterone administration amplify viewing preferences for sexual images in male rhesus macaques. Phil Trans R Soc B. 2022;377(1858):20210133. doi:10.1098/rstb.2021.0133

8. Deaner RO, Khera AV, Platt ML. Monkeys Pay Per View: Adaptive Valuation of Social Images by Rhesus Macaques. Current Biology. 2005;15(6):543-548. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2005.01.044

9. Dellavigna S, Kaplan E. THE FOX NEWS EFFECT: MEDIA BIAS AND VOTING. QUARTERLY JOURNAL OF ECONOMICS.

10. Hardmeier S. The Effects of Published Polls on Citizens. In: The SAGE Handbook of Public Opinion Research. SAGE Publications Ltd; 2008:504-514. doi:10.4135/9781848607910.n48

11. Simon HA. Bandwagon and Underdog Effects and the Possibility of Election Predictions. Public Opinion Quarterly. 1954;18(3):245. doi:10.1086/266513

12. Farjam M. The Bandwagon Effect in an Online Voting Experiment With Real Political Organizations. International Journal of Public Opinion Research. 2021;33(2):412-421. doi:10.1093/ijpor/edaa008

13. Dahlgaard JO, Hansen JH, Hansen KM, Larsen MV. How Election Polls Shape Voting Behaviour. Scand Pol Stud. 2017;40(3):330-343. doi:10.1111/1467-9477.12094

Cover Image by Sinisa Maric from Pixabay

Figure 1 made with BioRender.com

Leave a comment