November 5th, 2024

Written by: Andrew Nguyen

Parasites are organisms that live on or inside of another living organism, called a host, to survive and feed off of. An underappreciated aspect of parasite biology is that they can cause some horrific health complications for the host brain, even leading to the development of neurological disorders. In one case, parasites can enter our bodies through the foods we eat, like undercooked meat, and make their way into the central nervous system– in a condition called neurocysticercosis (NCC). NCC is known for causing numerous neurological symptoms such as seizure disorders like epilepsy, motor and sensory deficits, and buildup of pressure in the brain. Epilepsy is a chronic seizure disorder that can be deadly and NCC is viewed as the leading preventable form of epilepsy. The parasite responsible for most NCC cases is a species of tapeworm called Taenia solium (T. solium) and is most commonly transmitted through eating undercooked pork that is a host to these tapeworms1. Learning about the biology of this tapeworm and how it affects the brain is a fascinating, horrifying, but understudied part of neuroscience.

There is a huge lack of awareness of NCC and other parasitic infections that invade the brain. NCC is one of five parasitic infections classified as a “Neglected Parasitic Infection” from the Center for Disease Control, meaning this disease is capable of causing severe illness and affects an estimated 2.5 to 8.3 million people worldwide. One key factor in being classified as a “Neglected Parasitic Infection” is that the resources to prevent and effectively treat NCC are limited, especially in areas around the world where NCC is common2. The World Health Organization considers NCC to be endemic, or commonly occurring, in many rural areas of “developing countries” across the world3. It is estimated that around 30% of seizure cases in these highly endemic areas also happen to occur with the presence of NCC. Even though understanding how this parasitic infection works evokes a strong sense of discomfort, understanding the underlying biology of how NCC is transmitted, develops, and how it affects the brain can lead to improved prevention, diagnostic tools, and accessible treatment interventions worldwide.

Finding their way in

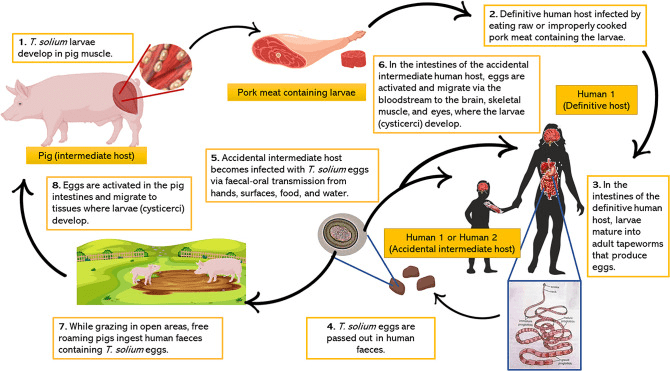

T. solium is most commonly contracted from eating undercooked infected pork, and if left untreated, can result in the larvae of T. solium invading other parts of the body– including the brain. NCC infection from T. solium larvae starts by accidentally consuming larvae from undercooked pork that develop into adult tapeworms within the intestines. These adults lay eggs that get passed through the digestive system and can be further transmitted orally through contaminated surfaces, food, or water4 (Figure 1). One important means of preventing infection is simply public health education about how these parasites find their way in so people know what actions to take to prevent infection.

Taking a peek inside

Taking a look at what happens after these parasites find their way into our bodies helps us understand what they do on the inside that can damage the brain and lead to neurological symptoms like epilepsy. Once ingested, these T. solium eggs develop into embryos that are able to bypass the mucus layer of the intestines enabling them to travel around the body into different tissues through the bloodstream. When embryos infiltrate the brain, they develop into larvae that resemble a fluid-filled cyst, or larval cysts. In order to diagnose NCC, doctors must scan the brains of NCC patients, to try and visualize these larval cysts. Although these larval cysts can create issues in the brain, many cases of NCC can go undetected because they don’t always show clear symptoms, like seizures, and doctors may not think to scan the brain for the parasites. This likely depends on the number of these larval cysts and where they are located in the brain. Brain scans of an NCC patient are usually characterized by random lesions, elevated levels of chemicals that are associated with inflammation or damage, disruption of the blood-brain barrier, and changes to the brain immune cells that are the first line of defense to pathogens and damage. All of these brain complications have been identified to be potentially important for NCC-induced epilepsy. Unfortunately these diagnostic tests may be limited in rural communities where rates of NCC are highest around the world. This is largely because the tools needed to diagnose and treat NCC are expensive, creating a big financial burden to these people.

Addressing the worms in the room

Now that we know about how NCC is transmitted and how it can damage the brain, this knowledge can hopefully be applied to helping treat NCC patients. Typically around 70% of active, symptomatic NCC cases also experience chronic epilepsy if left untreated5. Currently, treatment for NCC depends on the number of larval cysts, whether many of the cysts are active or dead, and the symptoms present. If the patient experiences many seizures, doctors may take a course of action that simply rides out the course of the parasites and treats the seizures. Otherwise, the patients may be prescribed medication to target the cysts and active parasites, taking on surgical procedures to extract the larval cysts in extreme cases. Accessibility to the right medication to treat NCC varies depending on the patient’s symptoms, number of active or dead larval cysts, and proximity to healthcare, treatment options for this neglected parasitic infection are another hurdle for the estimated 2.5 to 8.3 million people worldwide5.

Learning about how parasites wreak havoc on the human body and the brain can be terrifying, but ultimately sheds light on the reality of these common parasitic infections and how detrimental they can be. Public health awareness and mitigation strategies, like thoroughly cooking meat and properly washing hands and surfaces, could greatly reduce the number of NCC cases worldwide. Advancing the scientific understanding of infectious diseases like NCC can help identify and develop more effective, accessible diagnostic tools and treatment interventions.

References

- Garcia HH, Nash TE, Del Brutto OH. Clinical symptoms, diagnosis, and treatment of neurocysticercosis. Lancet Neurol. 2014 Dec;13(12):1202-15. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(14)70094-8. Epub 2014 Nov 10. PMID: 25453460; PMCID: PMC6108081.

- Cantey PT, Montgomery SP, Straily A. Neglected Parasitic Infections: What Family Physicians Need to Know-A CDC Update. Am Fam Physician. 2021 Sep 1;104(3):277-287. PMID: 34523888; PMCID: PMC9096899.

- WHO guidelines on management of Taenia solium neurocysticercosis [Internet]. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2021. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK573853/

- Steyn TJS, Awala AN, de Lange A, Raimondo JV. What Causes Seizures in Neurocysticercosis? Epilepsy Curr. 2022 Dec 21;23(2):105-112. doi: 10.1177/15357597221137418. PMID: 37122403; PMCID: PMC10131564.

- https://emedicine.medscape.com/article/1168656-overview#a1

Cover Photo by Ajay Kumar Chaurasiya on WikiCommons

Figure 1 from Steyn et al. shared under Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License.

Leave a comment