October 29th, 2024

Written by: Omer Zeliger

On NPR’s Invisibilia, neuroscientist Dr. Daniel Tranel and Patient S.M. discuss fear.

Dr. Tranel asks, “Tell me this, when do you remember feeling fear in your life?” And S.M. answers, “I believe when I was just a little girl.” S.M. and her father had gone fishing together and they’d hooked an impressive catfish. “You were afraid to take the fish off the hook.” “Yes, because I didn’t want to get bit. And that’s the only time when I can really remember, being afraid of the doggone fish when I was small.”1

That was the last time S.M., now in her fifties, remembers being afraid1,2.

What is fear?

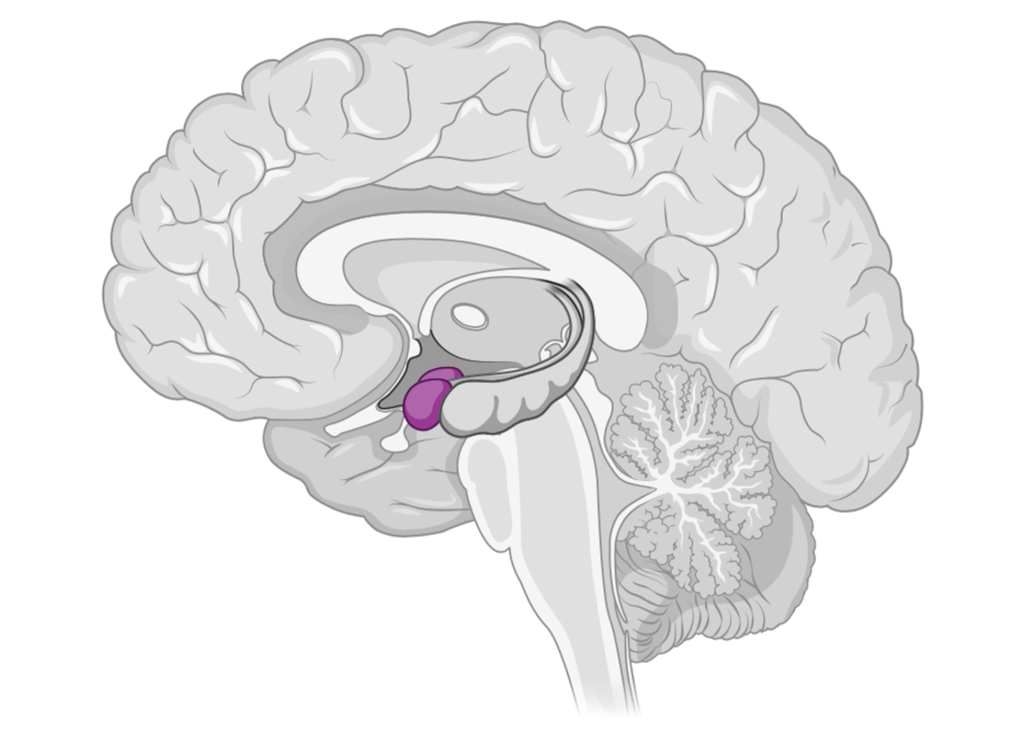

When you see something scary – say, a lion – you might start to feel your heart beat faster and feel your palms start to sweat. That’s thanks to a small part of the brain called the amygdala. This brain region is made up of two tiny almond-shaped structures (Figure 1). It is involved in processing several emotions, but is most often associated with fear. When you see a lion, the amygdala recognizes it as a threat and talks to other areas of the brain to kickstart the fear response, flooding the body with stress hormones and triggering a fight or flight response3.

At its best, fear can help us recognize and avoid danger, but when it stops working like it’s supposed to we can develop issues like phobias or post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD)4,5. Understanding the amygdala is the first step to developing better treatments for these conditions.

S.M.’s missing amygdala

S.M. is one of only ~400 people diagnosed with Urbach-Wiethe disease8, a rare condition that causes rocks to build up in the amygdala, eventually destroying it. By the time S.M. interviewed with neuroscience researchers in the late 80’s, her amygdala was almost completely gone6,7, leaving her with one unusual symptom – she could not feel fear1,2,9.

Though S.M. thinks of herself as a happy person, her fearlessness hasn’t come without consequences1. S.M. has difficulty recognizing and avoiding dangerous situations before it is too late, which has led to her being threatened at knife- and gunpoint more than once1,2. S.M.’s identity is closely guarded by the researchers who work with her, in part to protect her from being taken advantage of1.

Throughout the years, S.M. has volunteered for countless studies, helping us understand what role the amygdala plays in fear and emotion processing.

What has S.M. taught us about fear?

When S.M. says she can’t feel fear, what does that really mean? S.M. can still get startled by things like sudden noises and logically understands that she should avoid dangerous situations like speeding cars9. However, she gets much less scared than others when put in frightening situations like watching horror movies or visiting haunted houses2. S.M. has even been assaulted in the past, but has said the experiences made her feel angry and upset rather than afraid2. S.M. cannot be fear conditioned – that is, she doesn’t begin to instinctively fear something after it has hurt her10. She knows not to touch a pan straight out of the oven – it is hot, and would be painful if it burned her. However, her body wouldn’t exhibit a fear response when she thought about touching it; her heart wouldn’t race, and she wouldn’t start to sweat. S.M. has taught neuroscientists that the amygdala is crucial for feeling fear when put in threatening situations and when judging if something is likely to be dangerous.

Despite her numerous traumatic experiences, S.M. has not developed PTSD2, a common psychiatric disorder that often affects people who have experienced violent or emotionally upsetting events11. Scientists believe that S.M.’s amygdala damage protects her from the fear-based disorder2. Like S.M., combat veterans with amygdala damage are similarly resistant to PTSD12. This, along with other similar studies, means that studying the amygdala is crucial for understanding and treating PTSD.

Over the years, scientists have found only one situation that can make S.M. feel panic. Up until then she’d only been exposed to scary situations in her environment – but what if the threat was coming from inside her body? To test this, scientists asked her to breathe in carbon dioxide, which can safely simulate suffocation by signaling to the brain that it needs more air. This test often causes panic and fear in people with intact amygdalas. Scientists expected S.M. to react as fearlessly as she had in the past, but to their shock S.M. reported high levels of panic13. According to this experiment, the amygdala might not be necessary for feeling fear in and of itself – it might just be necessary for detecting threats in the environment and kickstarting fear when it finds one.

Besides her inability to feel fear, S.M. has other unexpected differences that have taught us that the amygdala does more than simply detecting threats. Usually, humans find emotional events more memorable than neutral ones. S.M. does not have this memory boost14. On top of that, her lack of amygdala has made it harder for her to notice when other people are afraid. Even though she has no problem recognizing facial expressions like happiness and disgust, she has trouble recognizing fear15.

The limitations of case studies

S.M.’s enthusiasm for participating in research has been invaluable for neuroscientists. It’s rare for brain injuries to completely damage only the amygdala with so little damage to the surrounding areas. S.M.’s unique amygdala damage gives scientists a rare opportunity to study life without an amygdala, without worrying that the results are affected by damage to other, unrelated areas.

However, S.M. is only one person – there are so many different people out there, each with their own quirks, and what we learn from S.M. likely doesn’t apply to all of them. On top of that, people can respond to the same type of brain damage in a spectrum of different ways16,17. Even the age at which brain damage occurs and how much of a brain area is left intact can have a massive impact on how well the brain adapts and recovers. You can read more about the pros and cons of unique case studies like S.M. here.

Two twins with Urbach-Wiethe disease, both with amygdala damage similar to S.M.’s, highlight just how differently people can be affected by injury to the same brain region. One of the twins, just like S.M., has trouble recognizing scared facial expressions16. The second twin, on the other hand, has no issue recognizing fear. When scientists checked, they noticed that areas of the brain associated with empathy were working overtime in the second twin, but not the first – other brain areas seemed to have taken over the amygdala’s job16. Despite how similar their injuries were, the twins recovered in very different ways from each other – and only one of them recovered like S.M. did. Though S.M.’s contributions to neuroscience research have been invaluable, scientific findings about her won’t necessarily be true for everyone else.

Patient S.M.’s legacy

Despite the baked-in issues that come with using case studies, S.M. has given us a strong foundation for understanding what the amygdala does for us in our daily lives. Thanks to her consistent willingness and eagerness to participate in neuroscience research, we’ve learned multiple ways the amygdala helps us identify and respond to danger. The studies she’s taken part in can and have inspired future experiments and given more evidence to back up existing ideas12. As Dr. Tranel and his colleagues write in Living Without an Amygdala, “we owe S.M. a tremendous debt of gratitude for her unwavering support of brain research and all of the incredible insights she has provided to the scientific community.”18

References

- Spiegel, A., & Miller, L. (Hosts). (2015, January 15). World With No Fear [Audio podcast episode]. In Invisibilia. NPR. https://www.npr.org/transcripts/377517810

- Feinstein, J. S., Adolphs, R., Damasio, A., & Tranel, D. (2011). The human amygdala and the induction and experience of fear. Current biology : CB, 21(1), 34–38.

- AbuHasan, Q., Reddy, V., & Siddiqui, W. (2023). Neuroanatomy, Amygdala. In StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing.

- Garcia R. (2017). Neurobiology of fear and specific phobias. Learning & memory (Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y.), 24(9), 462–471.

- Haris, E. M., Bryant, R. A., Williamson, T., & Korgaonkar, M. S. (2023). Functional connectivity of amygdala subnuclei in PTSD: a narrative review. Molecular psychiatry, 28(9), 3581–3594.

- Adolphs, R., Tranel, D., Damasio, H., & Damasio, A. (1994). Impaired recognition of emotion in facial expressions following bilateral damage to the human amygdala. Nature, 372(6507), 669–672.

- Tranel, D., & Hyman, B. T. (1990). Neuropsychological correlates of bilateral amygdala damage. Archives of neurology, 47(3), 349–355.

- Feltman, R. (2015, January 20). Meet the woman who can’t feel fear. The Washington Post. https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/speaking-of-science/wp/2015/01/20/meet-the-woman-who-cant-feel-fear/?hpid=z11

- Flatow, I. (Host). (2010, December 17). Living Without Fear [Audio podcast episode]. In Short Wave. NPR. https://www.npr.org/2010/12/17/132141793/living-without-fear

- Bechara, A., Tranel, D., Damasio, H., Adolphs, R., Rockland, C., & Damasio, A. R. (1995). Double dissociation of conditioning and declarative knowledge relative to the amygdala and hippocampus in humans. Science (New York, N.Y.), 269(5227), 1115–1118.

- American Psychiatric Association. (2022, November). What is Posttraumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD)?. https://www.psychiatry.org/patients-families/ptsd/what-is-ptsd

- Koenigs, M., Huey, E. D., Raymont, V., Cheon, B., Solomon, J., Wassermann, E. M., & Grafman, J. (2008). Focal brain damage protects against post-traumatic stress disorder in combat veterans. Nature neuroscience, 11(2), 232–237.

- Feinstein, J. S., Buzza, C., Hurlemann, R., Follmer, R. L., Dahdaleh, N. S., Coryell, W. H., Welsh, M. J., Tranel, D., & Wemmie, J. A. (2013). Fear and panic in humans with bilateral amygdala damage. Nature neuroscience, 16(3), 270–272.

- Adolphs, R., Cahill, L., Schul, R., & Babinsky, R. (1997). Impaired declarative memory for emotional material following bilateral amygdala damage in humans. Learning & memory (Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y.), 4(3), 291–300.

- Barrett L. F. (2018). Seeing Fear: It’s All in the Eyes?. Trends in neurosciences, 41(9), 559–563.

- Becker, B., Mihov, Y., Scheele, D., Kendrick, K. M., Feinstein, J. S., Matusch, A., Aydin, M., Reich, H., Urbach, H., Oros-Peusquens, A. M., Shah, N. J., Kunz, W. S., Schlaepfer, T. E., Zilles, K., Maier, W., & Hurlemann, R. (2012). Fear processing and social networking in the absence of a functional amygdala. Biological psychiatry, 72(1), 70–77.

- Umeda, T., & Funakoshi, K. (2014). Reorganization of motor circuits after neonatal hemidecortication. Neuroscience research, 78, 30–37.

- Amaral, D., & Adolphs, R. (Eds.). (2016). Living without an amygdala. The Guilford Press.

Cover photo by SerenityArt via Pixabay