October 8th, 2024

Written by: Sophie Liebergall

From the outside, it may seem like all published scientific research merely states cold, hard facts on which all the experts agree. But, if you were to peek in a session at a scientific conference, or attend a research group’s lab meeting, you might find that most scientists may have more biting commentary on the current research in their field than you would expect! Though controversy within a scientific field might seem like a point of weakness on the surface, debate and discussion are important drivers of scientific progress. Controversy can be healthy for a scientific field, as it pushes scientists to retest old assumptions and maintain the quality of their work. In this article we dip our toes into a few exciting controversies within neuroscience and try to understand why even the experts may still be at odds on some of the most challenging questions about how the brain works.

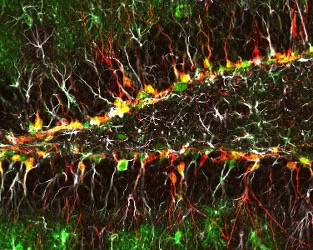

1. Are new neurons ever born in the brains of adult humans?

For most of the history of neuroscience, researchers took it as fact that the main cells in the brain that send and receive electrical signals – called neurons – are born when a mammal is still in the womb. This means that the neurons that you have in your brain now are the same ones that you had when you were an infant. And they will be the same ones that you have in old age. However, this idea was challenged by the neuroscientist Joseph Altman in 1965 when he discovered that there may be “adult-born” neurons in the brains of adult rats.1 In his experiments, Altman labeled the brains of adult rats with a radioactive molecule that marks when a neuron’s genetic material has been recently made. If a neuron’s genetic material was recently made, he reasoned that the neuron must have been born recently. To everyone’s surprise, he found that there were indeed newborn neurons in the adult rat brain, but they were specific to a region called the hippocampus, which plays an important role in controlling learning and memory. In the decades since Altman’s discovery, an entire field has sprung up around studying the characteristics of these cells and the role that they may play in brain functions like learning in both health and disease.

Using a technique that is similar to Altman’s but doesn’t use radioactivity, adult-born neurons have been discovered in the hippocampi of mammals ranging from mice to monkeys.2 However, there is controversy surrounding whether or not adult-born neurons can be found in the brains of humans. For practical and ethical reasons, it is hard to acquire and perform experiments on human brain tissue. Many of the ways of labeling adult-born neurons in lab animals, such as the experiment that labels newly-made genetic material, are much harder to perform in human tissue. This has lead to creative efforts by researchers – such as one study where the scientists tried to detect levels of atomic bomb-generated carbon-14 in the brains of people who were adults during Cold War atomic bomb tests.3 But many of these studies were hard to repeat and were only able to report indirect evidence of adult-born neurons.

The controversy came to a head in 2018 when two studies were published with directly conflicting results. One study showed that some new neurons were born in humans during infancy and early childhood, but by age seven, the birth rate of new neurons had shrunk to nearly zero. In contrast, the other study found that new neurons were born in the hippocampus all the way through adulthood.4,5 The contradictory results of these studies may be due to the two different groups of researchers using slightly different conditions in their experiments. For example, the two groups used different methods to count the number of cells labeled with a marker. Even if the studies claiming the presence of adult-born neurons in humans are not false positives, these adult-born cells are likely very rare and would account for only a few thousand out of the estimated 86 billion neurons in the human brain. No matter what, it is always wise to try to take care of the neurons that you already have!

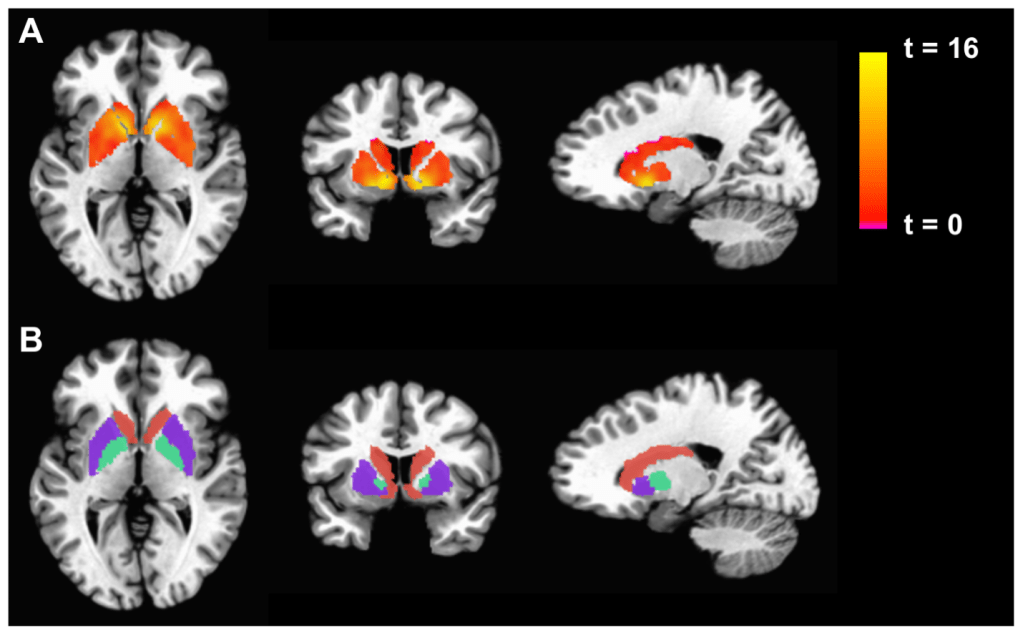

2. What does fMRI data tell us about how human brains work?

If you’ve read any news stories about neuroscience in the popular media, you’ve probably read about a study that uses a technique called functional MRI (or fMRI, for short). Since its development in the 1990s, fMRI has been used in over 40,000 neuroscience studies, including studies that claim to decode the subconscious political opinions of swing voters, determine whether a patient in a coma is actually conscious, and reconstruct language using AI. But in recent years, fMRI research has been the target of critics who believe that many studies using fMRI may be incorrectly interpreting or overstating their results.

So, what exactly is fMRI and what can it tell us? fMRI uses similar technology to a structural MRI that your doctor may order as a diagnostic test. However, fMRI doesn’t just take a picture of the structure of the brain – instead, it measures how much oxygen is being delivered to different parts of the brain in real time.6 Researchers often opt to use fMRI in human neuroscience studies because it is extremely safe, doesn’t require surgery, and the researchers can instruct subjects to do a task during the study. But, despite the fact that it is often advertised as such, fMRI cannot directly measure brain activity. The brain is “active” when individual neurons become active and send electrical signals to each other. Whereas, as we learned above, fMRI measures the delivery of oxygen to a region of the brain. We generally assume that when individual neurons in a region become active, the body tries to deliver more oxygen to this region to “feed” these busy neurons. But this may not always be true. For example, it is thought that the ability to regulate how much oxygen is delivered to the brain is altered during aging.7 Thus, older people may have “noisier” fMRI scans where the signal may not correlate as well with the activity of neurons. fMRI can give us a sign that many neurons in a large region are becoming active at the same time, but it isn’t directly measuring the activity of the brain cells themselves.

Because fMRI is an indirect measure of the neuronal activity, and because these signal in these studies can be affected by many factors outside of the design of the experiment, it is very important to interpret these results with caution and in context. Unfortunately, many of the first papers to use this technology didn’t apply a sufficiently high standard when performing statistical analyses and often reported overexaggerated conclusions.8 When analyzing fMRI data, researchers generally compare the signal at each 3D pixel in the image (Figure 2). An fMRI scan can have up to 130,000 of these 3D pixels. With so many data points, researchers have a high likelihood of finding something that looks like an interesting brain signal, but really just occurred by chance. This potential danger was put on full display by a study in which researchers put a dead salmon in an fMRI scanner (yes, you read that right) and showed the salmon pictures of human social interactions. They then analyzed the data using techniques that were considered standard in the field. Their analysis found that some areas in the dead salmon were selectively activated by the human social interactions – findings which were obvious false positives. Most fMRI researchers now take special care to use statistical methods to correct for the possibility of false positives. And to further ensure that conclusions from fMRI studies are real and not just due to statistical change, some researchers have been devoted to creating data banks so that multiple labs can access and analyze the same fMRI data from large groups of participants to confirm each other’s conclusion. Even though fMRI data can provide a unique window into what’s happening in a human brain, some scientists warrant caution when reading these studies and the flashy headlines that often accompany their reports in the popular media.

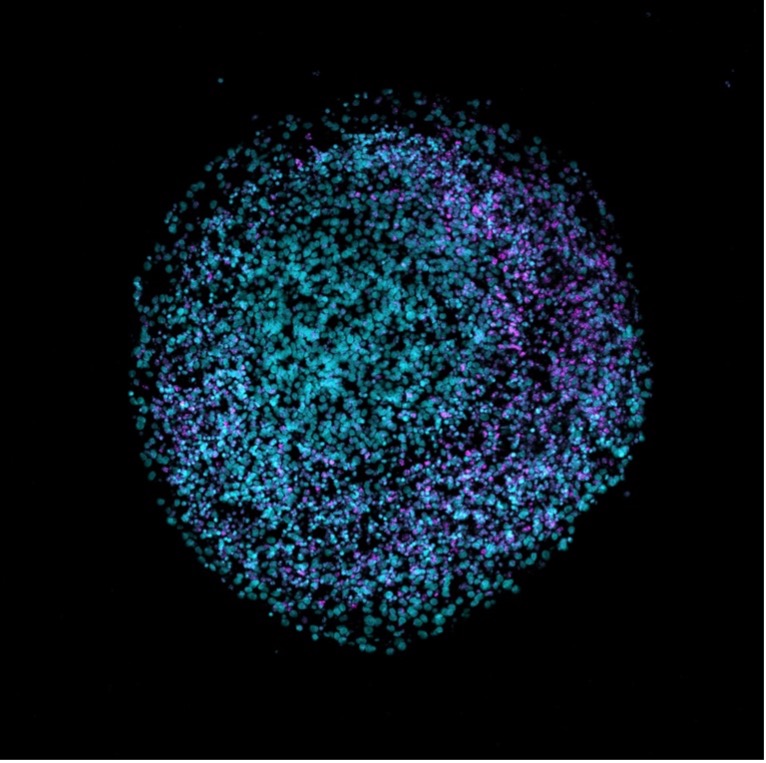

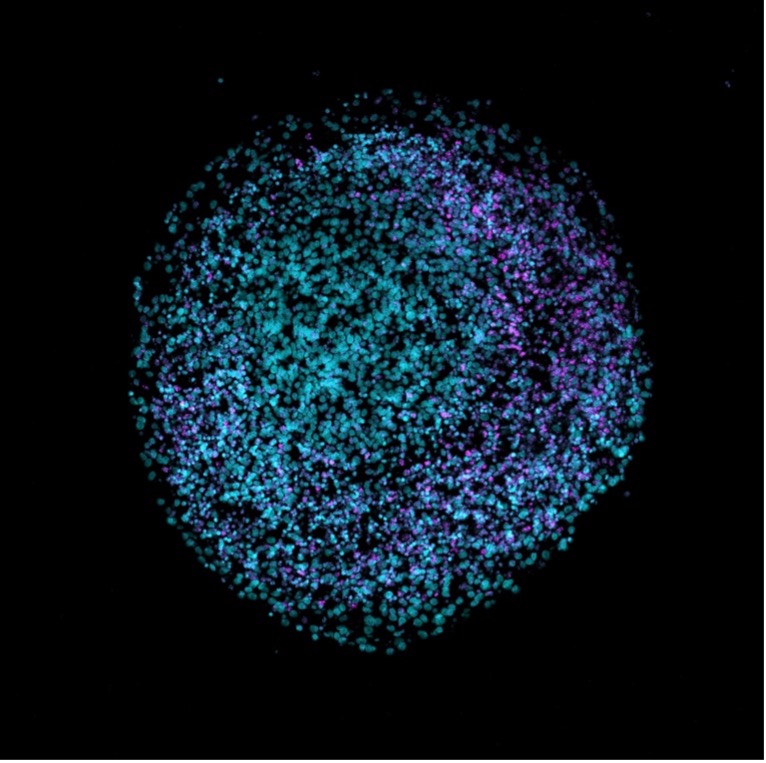

3. Are human brain organoids really “miniature brains” and what can they tell us about brain function?

Another way that scientists have tried to study human brains in greater detail than an fMRI scan provide has been through trying to grow pieces of human brain tissue in a dish. These are brain organoids, often called “mini brains” in the popular media.9 To make brain organoids, scientists first need human stem cells. Just like a little kid can grow up to become a doctor, or an artist, or a firefighter, stem cells are unique in that they can become any cell type in the human body. The scientists then put these stem cells in a dish and add different chemicals that instruct the cells to become brain cells. In the dish, these brain cells can start to behave as if they were in a developing human embryo – they multiply and start to form structures that you would see in a real brain, like specialized layers and liquid-filled cavities.

Brain organoids are an exciting tool to study how brains work, especially for researchers interested in aspects of brain development that are specific to humans and can’t be studied in other animals. For example, some patients with genetic neurologic disorders have changes in genes that are only found in humans. These disorders can’t be studies in animals, but you may be able to create an organoid with the gene change found in patients. However, some scientists have raised caution that the current state of organoid technology has been overstated, especially in popular media.10 There are many reasons that organoids aren’t truly “mini brains” in a dish. For example, organoids lack a circulatory system, which is crucial for delivering oxygen and nutrients to and clearing waste from the inner core of the organoid.

Human brains develop very slowly. Because organoids are made of human cells, they also grow very slowly. But organoids lack crucial components for long term maintenance of a healthy brain, like a circulatory system. Thus, their growth will often plateau before the brain cells can mature beyond those of a fetus. Some scientists think that organoids should only be used for research on specific questions in early human brain development. But, despite this limitation, other scientists have still tried to use organoids to study adult brain functions and neurodegenerative diseases like Alzheimer’s.11

Another important way that organoids are different than human brains is that they aren’t connected to body that can interact with the world around it. Organoids don’t receive sensory information from eyes or ears or touch receptors. And they also can’t send information like telling a muscle to move or reminding the lungs to breathe. There is a great deal of evidence that a brain’s interactions with the outside world can profoundly alter its structure and are important for its development.12 This has led some scientists to object to studies that try to interpret the electrical signals generated by a brain organoid in the same way that we would interpret them in a real human brain, such as recent studies that have compared electrical recordings from organoids to the seizure activity in humans with epilepsy.13,14

Considering the limitations of organoids is not just important for scientists seeking to use organoids in their experiments, but it is also important when explaining organoid technology to non-scientists as well. Irresponsible reporting can lead to a misperception that some neuroscientists are growing “mini brains” sophisticated enough to develop consciousness and a sense of personhood in their labs. This misperception could stoke a public backlash against the ethics of organoid research, which could then shut down a potentially important tool to further our understanding of the brain and develop treatments for neurological disorders.

The brain is the most complex and poorly understood organ in our body – some scientists think it may be one of the most complex objects in the universe! Thus, it is unsurprising that some disagreements may arise between researchers as they feel along the edges of the unknown. But in the long history of science, controversies have often sown the ground for new discoveries. So perhaps it is time for something groundbreaking to emerge in the fields of adult neurogenesis, human functional brain imaging, and creating models for human brains!

References

1. Altman, J. & Das, G. D. Autoradiographic and histological evidence of postnatal hippocampal neurogenesis in rats. Journal of Comparative Neurology 124, 319–335 (1965).

2. Alshebib, Y., Hori, T., Goel, A., Fauzi, A. A. & Kashiwagi, T. Adult human neurogenesis: A view from two schools of thought. IBRO Neuroscience Reports 15, 342–347 (2023).

3. Spalding, K. L. et al. Dynamics of Hippocampal Neurogenesis in Adult Humans. Cell 153, 1219–1227 (2013).

4. Boldrini, M. et al. Human Hippocampal Neurogenesis Persists throughout Aging. Cell Stem Cell 22, 589-599.e5 (2018).

5. Sorrells, S. F. et al. Human hippocampal neurogenesis drops sharply in children to undetectable levels in adults. Nature 555, 377–381 (2018).

6. Glover, G. H. Overview of Functional Magnetic Resonance Imaging. Neurosurg Clin N Am 22, 133–139 (2011).

7. D’Esposito, M., Deouell, L. Y. & Gazzaley, A. Alterations in the BOLD fMRI signal with ageing and disease: a challenge for neuroimaging. Nat Rev Neurosci 4, 863–872 (2003).

8. Brown, E. N. & Behrmann, M. Controversy in statistical analysis of functional magnetic resonance imaging data. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 114, E3368–E3369 (2017).

9. Eichmüller, O. L. & Knoblich, J. A. Human cerebral organoids — a new tool for clinical neurology research. Nat Rev Neurol 18, 661–680 (2022).

10. Kataoka, M., Gyngell, C., Savulescu, J. & Sawai, T. The importance of accurate representation of human brain organoid research. Trends in Biotechnology 41, 985–987 (2023).

11. Venkataraman, L., Fair, S. R., McElroy, C. A., Hester, M. E. & Fu, H. Modeling neurodegenerative diseases with cerebral organoids and other three-dimensional culture systems: focus on Alzheimer’s disease. Stem Cell Rev Rep 18, 696–717 (2022).

12. Holtmaat, A. & Svoboda, K. Experience-dependent structural synaptic plasticity in the mammalian brain. Nat Rev Neurosci 10, 647–658 (2009).

13. McCrimmon, C. M. et al. Modeling Cortical Versus Hippocampal Network Dysfunction in a Human Brain Assembloid Model of Epilepsy and Intellectual Disability. 2024.09.07.611739 Preprint at https://doi.org/10.1101/2024.09.07.611739 (2024).

14. Samarasinghe, R. A. et al. Identification of neural oscillations and epileptiform changes in human brain organoids. Nat Neurosci 24, 1488–1500 (2021).

Figure 1: Anna Engler, Wikimedia Commons

Figure 2: Miller AH, Jones JF, Drake DF, Tian H, Unger ER, Pagnoni G (2014) Decreased Basal Ganglia Activation in Subjects with Chronic Fatigue Syndrome: Association with Symptoms of Fatigue. PLoS ONE 9(5): e98156. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0098156 (Creative Common license)

Figure 3/Cover photo: Nresi1, Wikimedia Commons