September 157h, 2024

Written by: Catrina Hacker

The brain is a fascinating but complicated organ. Much of what makes neuroscience difficult is wading through this complexity to pinpoint exactly which groups of neurons produce the intricate behaviors and experiences that define our day-to-day lives. Throughout the history of neuroscience, descriptions of the difficulties that patients experience when they have damage to specific brain areas have been a powerful tool for doing just that. These detailed studies of a single patient (or even a chicken), called case studies, can be both fascinating and insightful. Let’s dive into what makes case studies so impactful and describe a few examples.

What can neuroscientists learn from a case study?

The cases studies I will highlight involve patients whose behavior is impacted by brain damage. These cases are helpful to neuroscientists because they teach us that a particular brain region plays an important role in whatever function is impacted. For example, if after experiencing damage to brain region X a patient could no longer smell bananas, it would suggest that the neurons in brain region X are necessary to smell bananas. Until recently, it wasn’t possible to measure brain activity in human patients, so case studies were the best way to learn what parts of the brain are important for functions like language and personality. Even with modern technology that allows us to visualize human brain activity, we can only know that certain groups of neurons are active when engaged in a particular function, not necessarily that they cause that function. Case studies following brain damage can go one step further to demonstrate that certain parts of the brain are indeed necessary to produce a behavior.

Neuroscientists owe a lot to the selfless patients who give their time to these studies. In most cases they do so for the sake of advancing our understanding of the brain with no promise that they will ever see a treatment or cure for their condition. Some of the most foundational studies in neuroscience involve patients who were willing to participate in years of experiments. You can read about another such patient, H.M., in another recent post.

Learning about language

Every introductory neuroscience course includes a description of Louis Victor Leborgne, nicknamed “Tan”. Leborgne, who experienced seizures from a young age, was admitted to the Bicêtre Hospital in France in 1839, having lost the ability to speak1. For the rest of his life, he could speak only one word: “tan”. Dr. Paul Broca, a surgeon who cared for Leborgne, took detailed notes on his condition. He documented that Leborgne was paralyzed on the right side, had difficulty swallowing, and although he could speak only one word the features of his voice were otherwise typical. While Leborgne couldn’t speak or write due to the paralysis, he was able to communicate through hand gestures and facial expressions, indicating that he had no problem understanding speech or forming thoughts.

When Leborgne died in 1861, Dr. Broca did an autopsy and noted that a part of his brain was damaged, possibly from a stroke. The brain region would come to be known as Broca’s area and is thought to play an important role in our ability to form words and speak. This early study paved the way to our understanding of how the brain coordinates the complex task of language by pinpointing a region necessary for the production, but not the understanding of speech. Today, the diagnosis for patients who struggle to form speech is called Broca’s aphasia, named after Broca’s first documentation of Leborgne’s deficits.

What makes you, you?

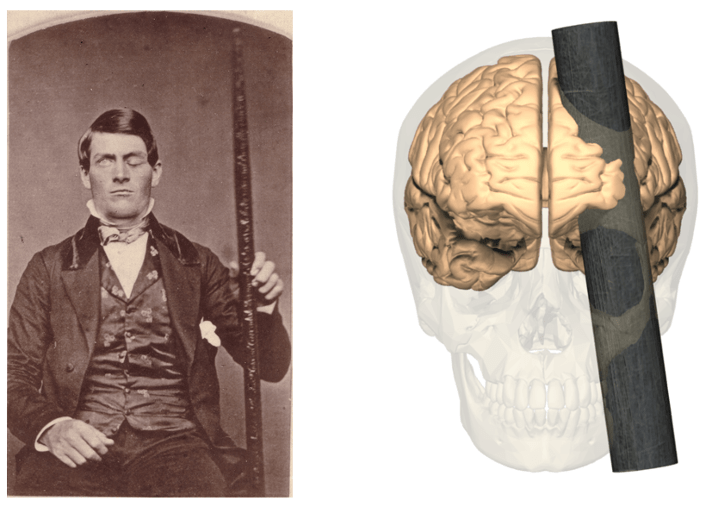

In 1848, then 25-year-old Phineas Gage got into a serious accident whose consequences would lay the foundation of our understanding about how the brain gives rise to personality2. While working on the railroad, an unexpected explosion caused a 6 kg, 1.1 m long rod to go through Gage’s cheek and out his skull, partially destroying an area of his brain called the frontal cortex (Figure 1). Miraculously, Gage survived after spending several months in the hospital. However, in the weeks after his physical recovery, Gage’s doctors and colleagues noticed that his personality had changed. He was stubborn, childish, and driven only by his momentary desire. He would often throw fits and yell profanities, despite never having done so before the accident. He was able to hold conversations and take care of himself, but reverted to childlike levels of decision making. Unfortunately, the change was so profound that he lost his job. His doctor reported, “his mind was radically changed, so decidedly that his friends and acquaintances reported that he was ‘no longer Gage’”. He went on to join Barnum’s Circus, before returning home to his family.

We still have a long way to go in piecing together the puzzle of how our brains make each one of us uniquely ourselves, but Gage’s case was the first to show that there are particular parts of the brain that influence personality. Today, neuroscientists are indebted to Gage as they build on that knowledge to understand things like personality disorders.

Living without fear

We all have moments we wish we could be fearless, but for S.M., a happy mother of three, that’s just a typical day. S.M. was born in 1965 with a rare disease called Urbach-Wiethe disease that destroyed a part of her brain called the amygdala3 early in her childhood. As a result, S.M. fears nearly nothing. When presented with a frightening situation like handling a snake or watching a scary movie, S.M. shows only curiosity and excitement4. She cannot recognize fear in the facial expressions of other people3, and has been the victim of many crimes as she struggles to identify threats and dangerous situations3. Interestingly, some of S.M.’s differences in emotional processing go beyond just fear. Most people can remember any kind of emotional event better than a neutral one, but for S.M. an emotional event is just as memorable as a neutral one, suggesting that the amygdala is where emotional memories are enhanced in our memory5.

Studying S.M. has taught us many important things about the function of the amygdala, especially in its role in emotional, especially fear-based, processing. These insights are being used to motivate further studies investigating treatments for disorders like PTSD.

The legacy of the case study and neuroscience in the modern era

Case studies have been, and continue to be, a core tool in the neuroscientist’s toolbox. Specifically, they have been essential for identifying where certain brain functions may be implemented in the brain, providing targets for treatments and further research studies. Over the last several decades the technology we can use to measure brain activity has significantly improved, allowing neuroscientists to leverage hints about where these processes are implemented to further study exactly how they are implemented.

The use of case studies has led to many advances, but they also have limitations. Damage is rarely specific to just one part of the brain, so interpreting deficits can be tricky. The brain is also a flexible organ and sometimes new brain regions can take over for damaged brain areas to prevent too many deficits. This can make interpreting symptoms and their relationship to a damaged brain area complicated. In addition, many of these studies assume that brain functions can be localized to a single part of the brain, but it’s becoming more clear that complicated processes like personality or emotion likely rely on many brain regions acting together to function properly. All that being said, there remains a strong case for the importance of case studies in neuroscience.

*If you enjoyed this post, you may also enjoy books written by Oliver Sacks, including his bestseller, “The Man Who Mistook his Wife for a Hat”.

References

1. Mohammed, N., Narayan, V., Patra, D. P. & Nanda, A. Louis Victor Leborgne (“Tan”). World Neurosurg. 114, 121–125 (2018).

2. Martyn, C. Snapshots from the decade of the brain. BMJ 317, 1673–1673 (1998).

3. Adolphs, R., Tranel, D. & Damasio, H. Impaired recognition of emotion in facial expressions following bilateral damage to the human amygdala. 372, (1994).

4. Feinstein, J. S., Adolphs, R., Damasio, A. & Tranel, D. The Human Amygdala and the Induction and Experience of Fear. Curr. Biol. 21, 34–38 (2011).

5. Anderson, A. K. & Phelps, E. A. Lesions of the human amygdala impair enhanced perception of emotionally salient events. Nature 411, 305–309 (2001).

Figure 1 made by Catrina Hacker using images from Wikimedia Commons: image 1, image 2.

Cover photo by Wesley Tingey on Unsplash