September 10th, 2024

Written by: Joseph Stucynski

All of us have had days where things just never seem to go right. Maybe you miss your alarm and wind up late for work or school. During the day there might be some social interactions that really start to make you mad, like a coworker who won’t stop bothering you. As these kinds of things keep happening, you can feel yourself start to get more and more frustrated. And often by the end of the day any little thing can make you feel like you’re ready to snap. Emotions like anger and frustration can range from mild to very intense. But what’s going on in our brains to move us along the sliding scale of intensity we experience with our emotions?

How your neurons work together to process information

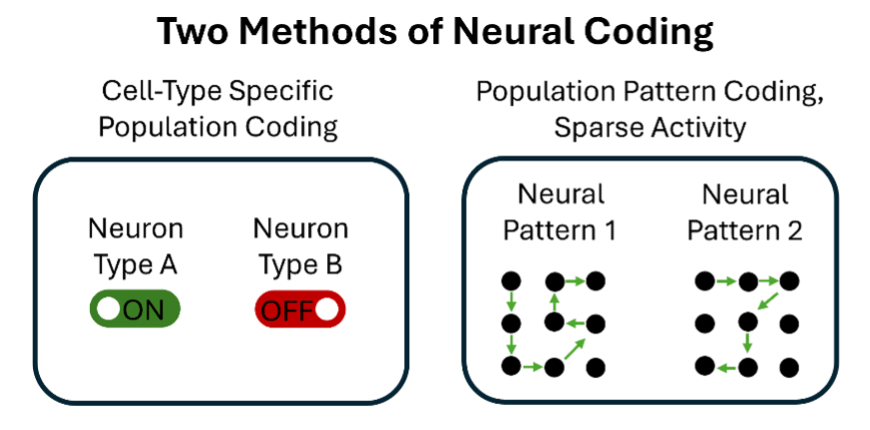

One central idea in neuroscience is that when neurons in your brain turn on or off, it directly leads to behaviors like emotions or physical actions. There are two prevailing ideas about how this could work. The most commonly discussed way is that groups of neurons in a given brain area that all have the same type serve the same purpose. For instance, if you were having a bad day and you stub your toe, there might be one type of neuron that turns on to make you feel the painful sensation, and another group of neurons nearby that turns on to make you feel angry and want to shout. In this case, different groups of neurons handle different aspects of behavior when they become activated. They act like switches that can be turned on and off. There are no in-between states.

Another way neurons could process information would be to change their patterns of activity. In the case where you stub your toe, this would instead be like the sequence of behaviors including feeling pain, becoming angry, and shouting were produced by the same group of neurons, with differences in which individual neurons are turned on or off for each behavior. Using this strategy, when neurons talk to each other they can represent many different variations of a behavior. Being able to represent behaviors on a sliding scale like this would be necessary for the brain to generate things like emotions that have different intensities. These patterns of neural activity have been very difficult to study in the brain because it requires being able to identify individual neurons working together in specific patterns, and then disrupting those patterns to see what happens to the behavior.1,2 Until recently the technology to do so did not exist. However, an exciting new set of studies are taking the first steps toward investigating whether this is a strategy that the brain implements.

Patterns of attraction

In a recent series of studies, one group of neuroscientists set out to find evidence that neurons in a part of the brain called the hypothalamus generate different intensities of aggressive behavior by relying on the pattern method of neural coding. They were interested in the hypothalamus because when they stimulated the hypothalamus neurons in mice they could cause the mice to begin an aggressive attack.3 Likewise, when they artificially turned off the neurons, they could prevent aggressive behavior. However, when they looked at the activity of the neurons while the mouse was attacking, they noticed something strange. At the moment of attack, there didn’t seem to be many aggression neurons that were active. This would argue against the neurons acting purely like a switch, and lead them to speculate that the brain activity associated with the aggression was characterized by specific patterns and not overall activity.

When they recorded neurons in the hypothalamus, they discovered that they used a specific kind of pattern coding called a neural attractor.3 Attractor dynamics are a mathematical concept that describe the ability of patterns to evolve in very regular and predictable ways. In this case, the neurons fire in one pattern that leads to another pattern, and so on, and each pattern governs one aspect of a behavior. If the activity of the neurons starts outside of the attractor pattern, or is pushed outside, they will be pulled back into the attractor pattern. For the neurons in the hypothalamus, it turns out that the neural attractor represents a sequence of activity patterns that represents the intensity of the aggressive emotion.

But one thing was still needed to prove that the hypothalamus neurons generated the attractor dynamics. Otherwise, it could be that the neurons activated in those patterns simply because other neurons in the brain told them to. This is an important point to investigate because not having direct evidence that neurons can organize like this has prevented a deeper understanding of how the brain processes complex information.1,2

To find this smoking gun, the neuroscientists were able to identify neurons in the hypothalamus that fired in the attractor patterns, and then stimulate a handful of those individual neurons.2 When they activated the neurons to disrupt the attractor patterns and then stopped the stimulation, the neurons fell back toward the original pattern. Likewise, when they stimulated the neurons in the same patterns they would normally be activated, they observed that the patterns evolved to the next patterns along the attractor dynamics. These two pieces are very good evidence that the hypothalamus aggression neurons naturally generate attractor dynamics.

Why is this important?

Neuroscientists have been searching for attractor patterns in the mammalian brain for a long time because in theory, attractors are a very good way of representing the many continuous behaviors that are so important for living.1 While past research has shown attractor dynamics involving neurons that control head direction in fruit flies, and also lateral eye direction in fish, it remained an open question whether the brains of more complex organisms like mammals used attractors.1

This research is the first direct evidence in mammals that the brain uses attractor dynamics to give rise to continuous internal states like emotion – in this case anger and aggression. Excitingly, the research team behind this finding has also extended the results to other behaviors,4 and also identified how the cells communicate together to give rise to these attractor dynamics.5 This provides further evidence that attractors are an important method of information processing in the brain across many contexts, and that they can arise from basic ways that cells communicate with one another.

These findings are an exciting first step into a new world of thinking about how the brain processes information. Given the breadth of ways that attractors can represent and process information, it’s likely that in the future we’ll uncover many more ways that the brain uses them to support important functions. So the next time you’re having a bad day, just remember all of the cool things your brain is doing that give rise to your emotions.

References

- Khona, M., Fiete, I. Attractor and integrator networks in the brain. Nature Reviews Neuroscience, 2024.

- Vinograd, A., Nair, A., Kim, J., Linderman, S., Anderson, D. Causal evidence of a line attractor encoding an affective state. Nature, 2024.

- Nair, A., Karigo, T., Yang, B., Ganguli, S., Schnitzer, M., Linderman, S., Anderson, D., Kennedy, A. An approximate line attractor in the hypothalamus encodes an aggressive state. Cell, 2023.

- Liu, M., Nair, A., Coria, N., Linderman, S., Anderson, D. Encoding of female mating dynamics by a hypothalamic line attractor. Nature, 2024.

- Mountoufaris, G., Nair, A., Yang, B., Kim, D., Vinograd, A., Kim, S., Linderman, S., Anderson, D. A line attractor encoding a persistent internal state requires neuropeptide signaling. Cell, 2024.

Cover image by pikisuperstar via Freepik.com

Leave a comment