July 23rd, 2024

Written by: Stephen Wisser

Recently, I had the pleasure of reconnecting with nature while camping in northern California. I was amazed by the vast diversity of plants and wildlife I saw in just this small section of the world. Considering all the unique forms of life on this planet, it’s no wonder that many common medicines come directly from or have been inspired by chemicals found in plants and animals. Aspirin and morphine for example, are two of the roughly 11% of life-saving drugs defined by the World Health Organization that come from flowering plants1. But in addition to drugs, nature has also directly provided lesser-known technologies that have revolutionized neuroscience research. In this post, I’ll focus on two such unsung heroes from nature that have provided valuable tools to neuroscientists and biologists which have had as big an impact on human health as plant-derived medicines.

Technology 1: Taq polymerase & PCR

Before we had rapid at-home COVID-19 tests, the gold standard way to test for COVID infection was a PCR test, which stands for polymerase chain reaction. The power of PCR goes beyond COVID testing however. In neuroscience, PCR is commonly used to detect viruses that cause neurological diseases like meningitis and encephalitis, help determine the best medicine for a patient who has HIV, and is routinely used in research to identify genes that play a role in many brain diseases2. Despite all the different uses for PCR, it generally works the same way for each application and relies on a special protein. This special protein called Taq polymerase was discovered in nature, specifically the hot springs of Yellowstone National Park in Wyoming (seen in the cover image). But why did we need this Yellowstone protein in the first place, and how did it allow us to create the PCR technique?

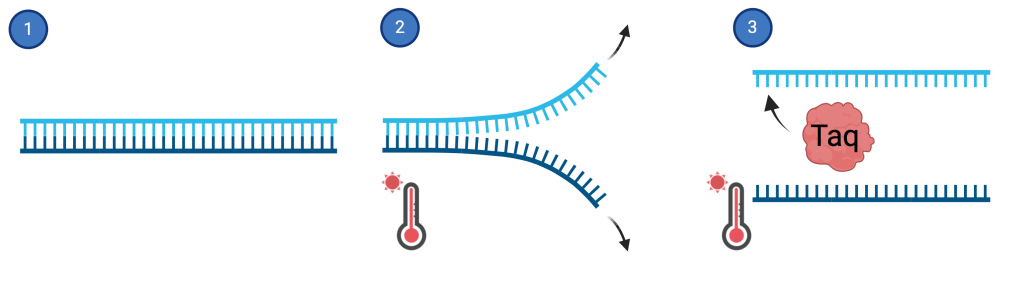

To hear the full story of Taq polymerase, we need to understand a bit about PCR. Imagine a forest that has just been destroyed by a fire. A single pinecone remains that drops its seed. In a few years, there are some small trees growing. It doesn’t look like a full forest yet, but each year new trees grow, drop pinecones, and these new seeds grow into more trees. Eventually this chain reaction of growth, seeds, and new trees all started from one pinecone becomes an easily recognizable forest. This is exactly how PCR works, except the original forest is DNA and the pinecone is a small section of that DNA. Small fragments of DNA are hard to study or even detect on their own, but the PCR technique replicates them billions of times in a chain reaction so they become easily recognizable, like a new forest of trees grown from the same starting pinecone. DNA is a double-stranded molecule meaning there are two “strings” that are connected to each other (figure 1.1). For DNA to be replicated in a PCR experiment, these two strings need to be separated first, and a good way to do that is by heating the DNA (figure 1.2). But the problem is that heat kills off a lot of important things needed to replicate the separated DNA. Enter Taq polymerase. Scientists discovered a special DNA replicating protein in the hot springs of Yellowstone that they named Taq polymerase since it comes from a bacteria called Thermus aquaticus3. Unlike many forms of life, this bacteria lives and thrives in the really hot temperatures of hot springs, so the special protein (Taq polymerase) from this bacterium works well at hot temperatures too. Thus, Taq can survive and replicate DNA in the hot temperatures needed to initially separate 2 strands of DNA in a PCR experiment (figure 1.3). Taq polymerase was the missing piece that scientists needed to build a forest from just one pinecone; that is replicate a small section of DNA so that it can be detected through the process of PCR. Just 12 years after the discovery of Taq, a reliable PCR method using Taq polymerase was invented4 which still serves as the basis for all of PCR today. By giving modern science Taq polymerase, nature built PCR and provided a way to replicate and detect DNA in many forms from COVID-19 to meningitis.

Technology 2: Jellyfish and Green Fluorescent Protein (GFP)

The old saying “a picture is worth 1000 words” especially holds true in the neuroscience research community where microscopy, the discipline of using a microscope to take a picture of a specimen, provides valuable data every day. To make these pictures worth their 1000 words, scientists often color specimens in a variety of ways, including by adding a simple dye, or by adding glowing molecules to specimens that make them shine under laser light. One powerful way to color specimens is to not add any dyes or glowing molecules to the specimen at all, but to make the specimen itself glow. Scientists accomplish this by making animals that contain fluorescent proteins, or proteins that glow in a cell when laser light is shone at them. By using fluorescent proteins in brain tissue, scientists can easily see and distinguish certain neurons from other types. Fluorescent proteins can even be put in the brains of live animals, allowing scientists to visualize these neurons while the animal goes about its life. This provides valuable data that can be used to understand brain diseases. But where did these glowing proteins come from? Like Taq polymerase, we have nature to thank for providing us with these fluorescent proteins which initially came from jellyfish.

Today, scientists have a whole palette of colors of fluorescent proteins we use to visualize neurons. The first fluorescent protein to be discovered was green fluorescent protein, or GFP, which glows green in response to certain light. GFP was first isolated from a bioluminescent jellyfish Aequorea victoria in 19625, but it wasn’t initially clear how GFP might be used in research6 or if it would work in more common lab animals like the mouse. Could GFP from a jellyfish be built into other animals? That answer came 32 years after its discovery when a different research lab successfully made worms with GFP7, showing the first example of how GFP could be used to identify specific cells in other animals. Shortly after, a 3rd group of scientists made a brighter version of GFP6,8, thus making it practical to use with today’s common microscopes. With the help of multiple groups of scientists, after 50 years GFP developed into a valuable research tool that allows the visualization of neurons in many different colors across multiple different species.

Conclusion

It’s easy to be amazed by the natural world, and indeed many scientists take inspiration from nature to design their experiments and develop questions they then test in the lab. In some cases, as discussed today with Taq polymerase and GFP, nature literally provides a tool for research. With the field of neuroscience rapidly expanding and asking more difficult and complex questions, there is no doubt that new research techniques will be invented to answer these questions. Since nature has already provided us with some great tools, it’s likely that many of these future technologies might come directly from another plant or animal. So next time you experience the outdoors, you just might be standing by the next hottest technique.

References

1 Pavid, Katie. “Aspirin, Morphine and Chemotherapy: The Essential Medicines Powered by Plants.” Aspirin, Morphine and Chemotherapy: Essential Medicines Powered by Plants | Natural History Museum, Natural History Museum, 19 Feb. 2021, http://www.nhm.ac.uk/discover/essential-medicines-powered-by-plants.html.

2 DeBiasi, Roberta L., and Kenneth L. Tyler. “Polymerase chain reaction in the diagnosis and management of central nervous system infections.” Archives of neurology 56.10 (1999): 1215-1219.

3 Chien, Alice, David B. Edgar, and John M. Trela. “Deoxyribonucleic acid polymerase from the extreme thermophile Thermus aquaticus.” Journal of bacteriology127.3 (1976): 1550-1557.

4 Saiki, Randall K., et al. “Primer-directed enzymatic amplification of DNA with a thermostable DNA polymerase.” Science 239.4839 (1988): 487-491.

5 Shimomura, Osamu, Frank H. Johnson, and Yo Saiga. “Extraction, purification and properties of aequorin, a bioluminescent protein from the luminous hydromedusan, Aequorea.” Journal of cellular and comparative physiology59.3 (1962): 223-239.

6 Swaminathan, Sowmya. “GFP: the green revolution.” Nature Cell Biology 11.1 (2009): S20-S20.

7 Chalfie, Martin, et al. “Green fluorescent protein as a marker for gene expression.” Science 263.5148 (1994): 802-805.

8 Tsien, Roger Y. “The green fluorescent protein.” Annual review of biochemistry 67.1 (1998): 509-544.

Cover photo by Jennifer from Pixabay

Figure 1 made with BioRender.com

Leave a comment