June 27th, 2024

Written by: Sophie Liebergall

You may be familiar with the common neuroscience myth that we only use 10% of our brains. This myth was the scientific basis of movies like Lucy and Limitless, and has been used to sell bogus “neuroenhancing” treatments. However, neuroscientists have spent centuries uncovering which regions of the brain control how we experience and interact with the world. And indeed, every area of the brain is responsible for an important function, whether it be sensing an object that we’ve touched, storing a memory of how that object felt, or telling our arm how to pick up that object. But there may be a kernel of truth contained within the 10% myth. When we zoom in on a particular part of the brain and look at the cellular level, the vast majority of individual brain cells appear to be mostly silent!

A minority of cells seem to bear the burden of the brain’s work

A main goal of neuroscience research is to try to understand how the electrical activity of brain cells called neurons translates into the many complex functions that are performed by our brain. And over decades of work, neuroscientists have discovered that within an area of the brain, individual neurons are responsible for different aspects of that brain area’s overall function. For example, within the part of the brain that is dedicated to processing sounds, individual neurons respond to particular frequencies of sound.1 Some neurons are only active during high frequency sounds, whereas other neurons are only active during low frequency sounds. In another example, within the part of the brain responsible for processing touch, individual neurons respond to sensations on different parts of the body.2 Some neurons only respond to sensations coming from your finger, whereas other neurons only respond to sensations coming from your nose. These “sensory maps” in the brain can be very detailed – in the region of a mouse’s brain that is responsible for sensing movement of its whiskers, there are neurons that only respond to movement of a particular whisker on the face.3

In the process of trying to map out which neurons are responsible for different aspects of a brain area’s function, neuroscientists discovered that only a small proportion of the neurons within a brain area could be mapped at all.4 At any given moment, most of the neurons in a brain area are completely silent. Why does the brain have so many seemingly silent neurons? Are they truly silent or do they serve some sort of function that we haven’t yet been able to measure? Would there be the effect on sensory perception if the “silent” neurons suddenly became active?

These questions were on the mind of Oliver Gauld when he began his PhD in Michael Hausser’s lab at University College London. During his PhD, Gauld and his colleagues would go on to shed some more light on silent neurons in a study published in the journal Neuron in May 2024.5

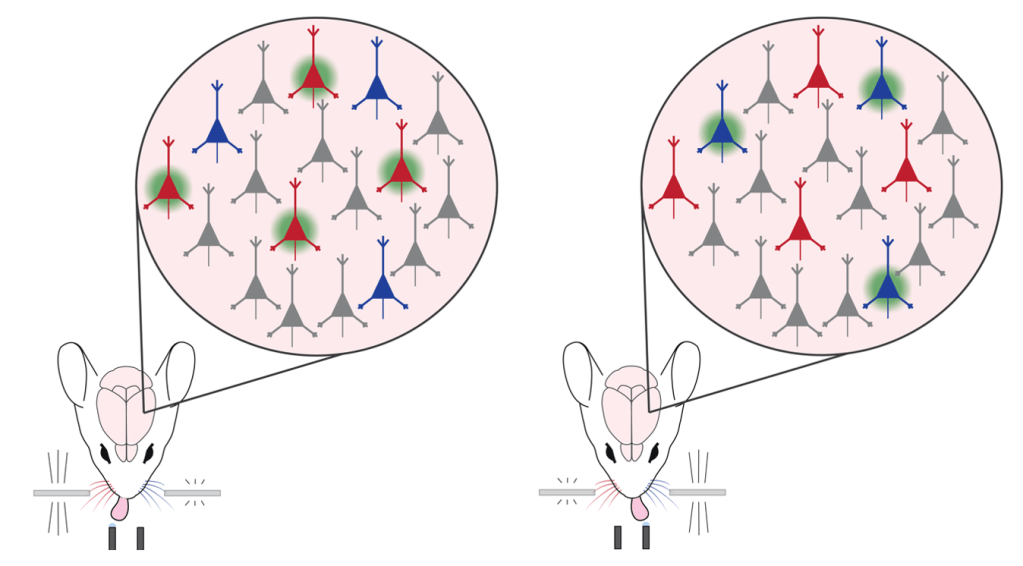

First, Gauld and his colleagues had to find a way to find and manipulate the silent neurons in the brain. They decided that they would use a combination of two techniques that would allow experimenters to both record and manipulate neurons at their will: two-photon imaging and two-photon optogenetics.6 In two-photon imaging, scientists modify the neurons of an animal so that they give off light when they are active (Figure 1). Then they can record the activity of these neurons with a specialized microscope, even while the animal is awake and behaving. In two-photon optogenetics, scientists perform an additional modification so that an experimenter can forcibly turn on a neuron when they flash it with red light. “The real breakthrough with this technology is that you can combine these two things simultaneously in the same experiment, which allows you to record activity from neurons but also manipulate the activity in the same neurons. It’s such a powerful tool that lets you do a bunch of cool, interesting experiments that we couldn’t previously do,” Gauld said of the combination of two-photon imaging and optogenetics, which was pioneered in the Hausser lab.

Training mice to tell us how they feel

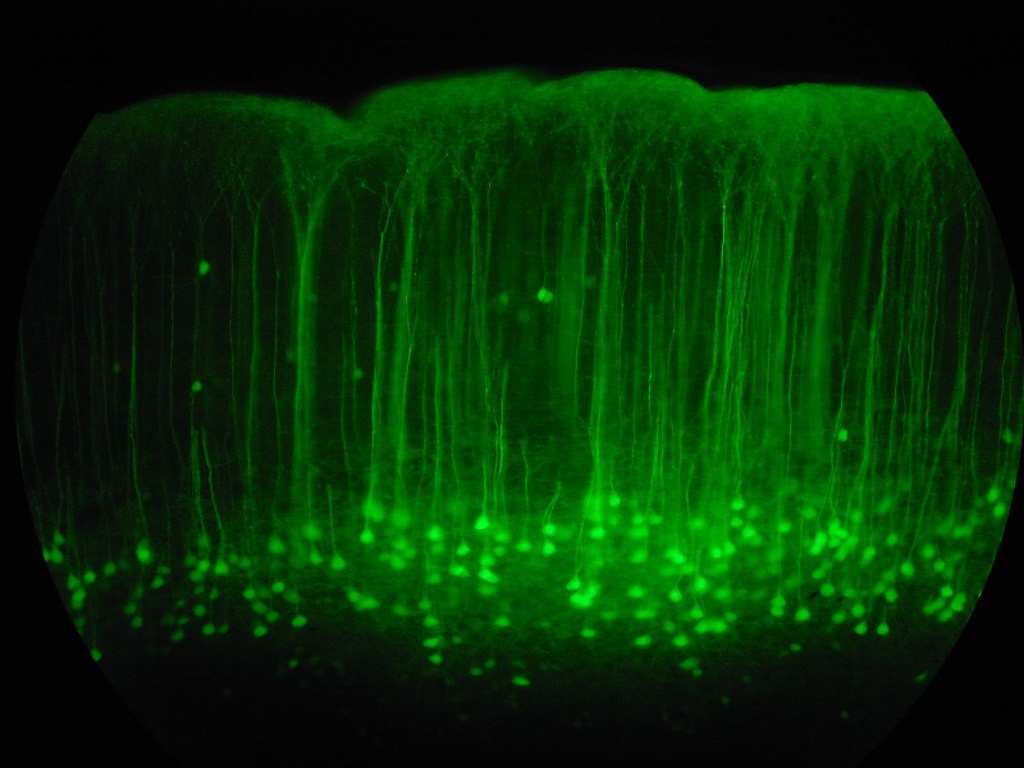

These powerful techniques have been optimized for use in mice, who are one of the mostly widely used animal species in neuroscience. But this means that Gauld and his colleagues had to come up with a way to test sensory perception in mice, who can’t simply tell us when they’re experiencing a sensation. Mice rely heavily on sensation with their whiskers as they navigate through tight spaces, often in the dark. Therefore, they devote a significant amount of real estate in their brain to whisker sensation, where there are particular neurons that are activated when the mouse’s individual whiskers are moved.3 To get a mouse to report their whisker sensation, the scientists trained the mice on a task where they moved the whiskers on both sides of the mouse’s face, then had the mice had to report whether their right or left whiskers were stimulated more strongly by licking one of two water spouts (Figure 2).

The mice became experts at accurately reporting whether their right or left whiskers were stimulated more strongly. Then the scientists measured the activity of the neurons in the brain while the mouse did the task. They found that in whisker sensing area there are three populations of neurons: neurons that were activated when the left whisker was stimulated more strongly, neurons that responded when the right whisker was stimulated more strongly, and neurons that remained silent when either whisker was stimulated.

Activation of “silent” neurons improves sensory perception

Now Gauld and his colleagues were ready to try to understand the function of the “silent neurons” by measuring any changes in perception when they forcibly “unsilenced” them. The scientists gave the mice a particularly hard challenge by stimulating the left and right whiskers very similarly while simultaneously activating the silent cells with two photon optogenetics. Then they assessed how their activation of the silent cells affected the mouse’s ability to determine whether the left or right whiskers were stimulated more strongly. To their surprise, they found that during activation of the silent cells, the mice were actually better at telling whether their left or right whiskers were being stimulated more strongly. In other words, unsilencing the “silent” neurons improved the mouse’s sensory perception.

There is still a great deal to learn about the role of the large number of silent neurons in our cerebral cortex. But this study has been an important first step in bringing attention to the potential function and power of these cells. “I think it would be nice to think that the ‘silent’ cells are available for function. This pool of neurons could exist as a resource which the brain can engage if it needs to increase its processing capacity or flexibly adjust the strength of a sensory representation,” Gauld says. He suggests that the next obvious experiments to do would be to see whether silent neurons have important roles in other brain areas or other behaviors.

The results from this study may also have implications for how we design devices that stimulate neurons in an attempt to improve cognitive performance or restore function after injury. “It challenges the viewpoint that you always need to manipulate the right neurons in the right task in the right brain regions [to improve function]. Some basic perceptual functions could be augmented or restored through more general manipulations which are technically a lot easier to do,” Gauld suggests. Perhaps scientists designing brain stimulation devices don’t need to go through the trouble of targeting the neurons that are thought to be specifically involved in a task. Instead, activating silent neurons, either through electrical stimulation or by using light (as the authors did in this study), may be a promising avenue for improving cognitive function.

References

1. Humphries, C., Liebenthal, E. & Binder, J. R. Tonotopic organization of human auditory cortex. Neuroimage 50, 1202–1211 (2010).

2. Wilson, S. & Moore, C. S1 somatotopic maps. Scholarpedia 10, 8574 (2015).

3. Erzurumlu, R. S. & Gaspar, P. How the Barrel Cortex Became a Working Model for Developmental Plasticity: A Historical Perspective. J Neurosci 40, 6460–6473 (2020).

4. Shoham, S., O’Connor, D. H. & Segev, R. How silent is the brain: is there a “dark matter” problem in neuroscience? J Comp Physiol A 192, 777–784 (2006).

5. Gauld, O. M. et al. A latent pool of neurons silenced by sensory-evoked inhibition can be recruited to enhance perception. Neuron 0, (2024).

6. Packer, A. M., Russell, L. E., Dalgleish, H. W. P. & Häusser, M. Simultaneous all-optical manipulation and recording of neural circuit activity with cellular resolution in vivo. Nat Methods 12, 140–146 (2015).

Cover Photo by Robert Cudmore on Wikimedia Commons.

Figure 1: Sophie Liebergall, Ethan Goldberg (unpublished data).

Figure 2: Created with Adobe Illustrator

Leave a comment