May 7, 2024

Written by: Jacob Parker

In the 1950s, neuroscientists were facing a serious dilemma. After centuries of scientific progress, scientists had labeled virtually every part of the brain, identified which of them were required for specific functions like seeing or speaking, and revealed that specialized brain cells called neurons are the fundamental cells that carry out these functions. They had even developed a sophisticated understanding of how these neurons generate electrical signals and convey these signals to other neurons1. However, a fundamental, yet profound question remained aggravatingly elusive2,3 – how does the activity of neurons, especially those in the brain, actually enable us to do things like see, speak, or think?

To give an idea of the enormity and the complexity of this problem, modern estimates suggest that there are around 86 billion neurons in the human brain4 that form 100+ trillion connections with each other5. Taking human vision as an example of something neuroscientists would like to understand, let’s suppose that only 10% of neurons contribute to our ability to see (large portions of our brain are involved in vision, so this is likely an underestimate). That means neuroscientists would need to account for how 8+ billion neurons and the trillions of connections between them actually enable us to do things like perceive a tree as a tree (as opposed to a meaningless blob of green light). This might be like trying to know exactly how every single one of the 8+ billion people in the world behave and interact with each other!

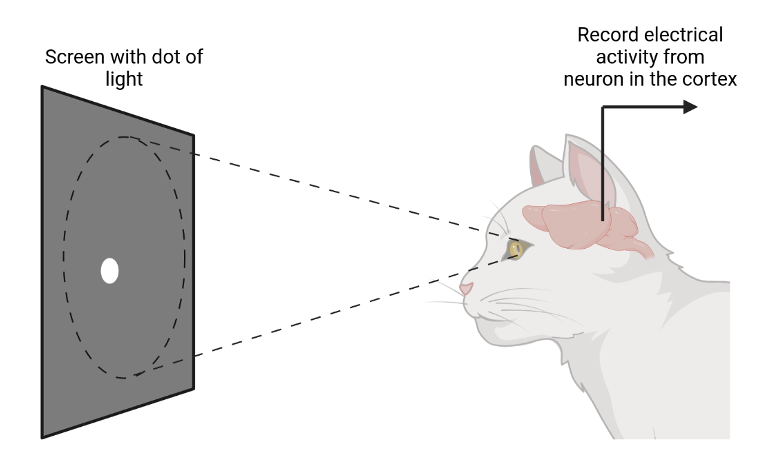

In the latter half of the decade, two young neuroscientists tackled this seemingly impossible challenge with a determination to match. In their experiments examining how the brain constructs our visual experience, David H. Hubel and Torsten N. Wiesel recorded the activity of neurons in cats while the cats viewed a screen that displayed small dots of light6,7 (Figure 1). By this point, other scientists had found that single neurons in the eye were strongly activated by a small dot of light displayed on a specific part of the screen3. Importantly, these neurons only responded when light was just within that specific dot – putting the dot of light somewhere else or making the whole screen light up failed to activate those specific neurons. Neurons responding in this way were also found within the thalamus, a structure deep within the brain that (in part) relays visual information from the eyes to the cortex, the large, wrinkled structure that covers the top of almost the entire brain. The cortex is where the most sophisticated processing of visual information occurs.

Figure 1. Experimental setup Hubel and Wiesel used to conduct their experiments.

Despite its massive importance to human vision, neuroscientists couldn’t find any patterns of light that reliably activated neurons in visual areas of the cortex like they did in the thalamus. Needless to say, it would be impossible to understand how the billions neurons of the brain constructed our visual experience without even knowing how a single neuron in the cortex contributed. And this problem was not just crucial for understanding vision. Scientists long knew that the cortex was essential for many of the functions and behaviors that make us human. It grants us a rich perception of the world around us in the form of sight, hearing, smell, taste, and touch. It allows us to effortlessly interact with that world by coordinating the complex movements of our body. It enables us to think about things we are not currently experiencing, whether they are in the past (memory) or the future (planning). Figuring out how the cortex and its neurons allow us to see would be a good first step to understanding all of this.

Unphased by many failed attempts by themselves and others to crack the neural code, Hubel and Wiesel continued trying out new patterns of light while recording from neurons in the cortex. They relentlessly tried pattern after pattern to no avail despite being warned this would happen8. One day they were going through the same process, swapping out slide after slide of different light patterns in the projector when suddenly the neuron responded very strongly while a new slide was being inserted. However, Hubel and Wiesel were perplexed because the neuron quickly fell silent. After experimenting some more, they soon realized that the neuron would go crazy whenever a new slide was inserted. Suddenly, they came to a realization. The neuron wasn’t responding to what was on the slide itself. It was responding to a slit of light formed by the edge of the slide8.

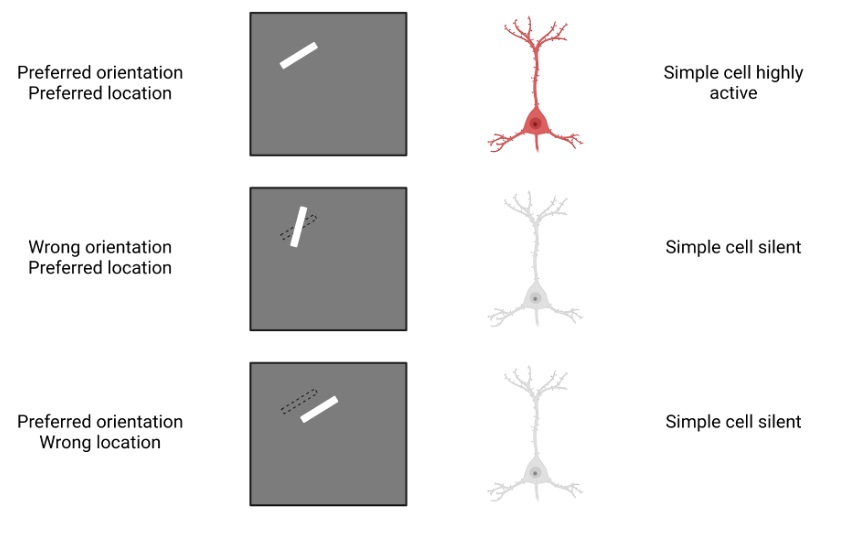

In a series of experiments hammering down this finding, they discovered that many neurons in the cortex responded vigorously when a rectangular bar of light oriented at a specific angle was displayed2,3,6–8. Each of these neurons, which are now called simple cells by neuroscientists, preferred different bar orientations and different locations on the screen. If a bar was shown either in the wrong location or at the wrong orientation, each simple cell would not activate (Figure 2). Between the countless simple cells in this region of cortex, all orientations and spatial locations are well represented. Hubel and Wiesel found another class of neurons in this region that are now called complex cells. For the most part, complex cells also prefer rectangular bars of light at specific orientations. In contrast to simple cells however, many complex cells respond strongly to the oriented bar over a wide region of space on the projector. Some complex cells are even only responsive if the oriented bar is actively moving in a specific direction. (Here is a video demonstrating the responses of these neurons in real time – the clicking sounds that can be heard is the sound of the neuron activating).

Figure 2. Response of a simple cell to various bars of light.

Upon cataloging these various visual neurons, Hubel and Wiesel began to realize what role this part of the cortex was playing in human vision. While neurons in the eye and thalamus detect the presence and location of spots of light in an image we see, these simple and complex cells highlight the presence and location of lines and edges. When we look at a scene, this helps us distinguish objects from each other and from the background as there are often distinct edges around each object. It also helps us perceive the form and contours of various objects, as simple and complex cells highlight the various lines that make up those objects6,7.

Perhaps most remarkable, Hubel and Wiesel provided an explanation of how simple cells in the cortex could detect these more complicated visual features7. Namely, they suggested that simple cells were wired to a group of neurons in the thalamus (the same ones mentioned previously) that each only respond to a small dot of light in a specific part of the screen. Crucially, the preferred light dot locations of these neurons fall along a straight line on the screen (Figure 3). Thus, a bar of light overlapping all of those individual points activates all of these neurons in the thalamus, which in turn all simultaneously activate a simple cell. Thus, it is by integrating the responses of several dot-selective neurons in the thalamus that simple cells in the cortex are able to detect bars of light (and thus lines and edges). Hubel and Wiesel similarly provided an explanation for complex cells. They suggested that complex cells are able to detect an oriented bar over a wide region of space because they are wired to a group of simple cells that respond to bars of the same orientation, but in different spatial locations. When any of those simple cells detects a bar, it responds and thus activates the complex cell.

Figure 3. How simple cells respond to specifically oriented bars of light.

Prior to these insights, neuroscientists had largely only characterized how single neurons in isolation responded to simple physical stimuli (small points of light, light touches of the skin, simple sound tones, etc). Hubel and Wiesel’s work illuminated for the first time how networks of many neurons wired together in specific ways could perform sophisticated computations, especially in the cortex. Indeed, based on these wiring principles, neuroscientists predicted and confirmed that additional regions of the cortex continued to combine these increasingly complex visual features9 until certain cortical neurons were responding to extremely specific and complicated patterns such as specific objects or faces10. Using these ideas as a scaffold, neuroscientists went on to discover that the cortex similarly constructed complex features for our sense of hearing11, organizing skilled movements12, and planning future actions13, among many other things.

Before 1959, the cerebral cortex and the brain at large was effectively a black box. Scientists knew what functions the brain was responsible for and cataloged extensively how humans and animals responded to various stimuli, but had virtually no understanding of how it worked. Hubel and Wiesel cracked open the black box for the first time and began the long process of inspecting its components. For this great service to neuroscience and human progress as a whole, Hubel and Wiesel were awarded the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine in 198114. While neuroscientists still have a long way to go before they finish illuminating the black box of the brain, they would certainly be far from where they are today without Hubel and Wiesel.

References

1. Hodgkin AL, Huxley AF. A quantitative description of membrane current and its application to conduction and excitation in nerve. J Physiol. 1952;117(4):500-544.

2. Wurtz RH. Recounting the impact of Hubel and Wiesel. J Physiol. 2009;587(12):2817-2823. doi:10.1113/jphysiol.2009.170209

3. Kandel ER. An introduction to the work of David Hubel and Torsten Wiesel. J Physiol. 2009;587(Pt 12):2733-2741. doi:10.1113/jphysiol.2009.170688

4. Azevedo FAC, Carvalho LRB, Grinberg LT, et al. Equal numbers of neuronal and nonneuronal cells make the human brain an isometrically scaled-up primate brain. J Comp Neurol. 2009;513(5):532-541. doi:10.1002/cne.21974

5. Pakkenberg B, Pelvig D, Marner L, et al. Aging and the human neocortex. Exp Gerontol. 2003;38(1):95-99. doi:10.1016/S0531-5565(02)00151-1

6. Hubel DH, Wiesel TN. Receptive fields of single neurones in the cat’s striate cortex. J Physiol. 1959;148(3):574-591. doi:10.1113/jphysiol.1959.sp006308

7. Hubel DH, Wiesel TN. Receptive fields, binocular interaction and functional architecture in the cat’s visual cortex. J Physiol. 1962;160(1):106-154. doi:10.1113/jphysiol.1962.sp006837

8. Martinez-Conde S, Macknik SL. David Hubel’s Vision. Sci Am Mind. 2014;25(2):6-8. doi:10.1038/scientificamericanmind0314-6

9. Tanaka K. Inferotemporal Cortex and Object Vision. Annu Rev Neurosci. 1996;19(Volume 19, 1996):109-139. doi:10.1146/annurev.ne.19.030196.000545

10. Tsao DY, Freiwald WA, Tootell RBH, Livingstone MS. A Cortical Region Consisting Entirely of Face-Selective Cells. Science. 2006;311(5761):670-674. doi:10.1126/science.1119983

11. Hickok G, Poeppel D. The cortical organization of speech processing. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2007;8(5):393-402. doi:10.1038/nrn2113

12. Wise SP, Boussaoud D, Johnson PB, Caminiti R. PREMOTOR AND PARIETAL CORTEX: Corticocortical Connectivity and Combinatorial Computations1. Annu Rev Neurosci. 1997;20(Volume 20, 1997):25-42. doi:10.1146/annurev.neuro.20.1.25

13. Miller EK, Cohen JD. An Integrative Theory of Prefrontal Cortex Function. Annu Rev Neurosci. 2001;24(Volume 24, 2001):167-202. doi:10.1146/annurev.neuro.24.1.167

14. The Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine 1981. NobelPrize.org. Accessed May 4, 2024. https://www.nobelprize.org/prizes/medicine/1981/summary/

Cover photo from Freepik.com

Figures 1-3 created by Jacob Parker with BioRender.com