September 26th, 2023

Written by: Sophie Liebergall

You’ve probably heard the term “brain waves” before, but I’d guess that you haven’t heard of a cortical spreading depolarization! Cortical spreading depolarizations (CSDs), also sometimes called just spreading depolarizations or, confusingly, cortical spreading depressions are an understudied brain phenomenon. But CSDs are actually the most dramatic “waves” that occur in the brain, and they are associated with a number of neurologic conditions including migraines, strokes, and seizures.

What is a cortical spreading depolarization (CSD)?

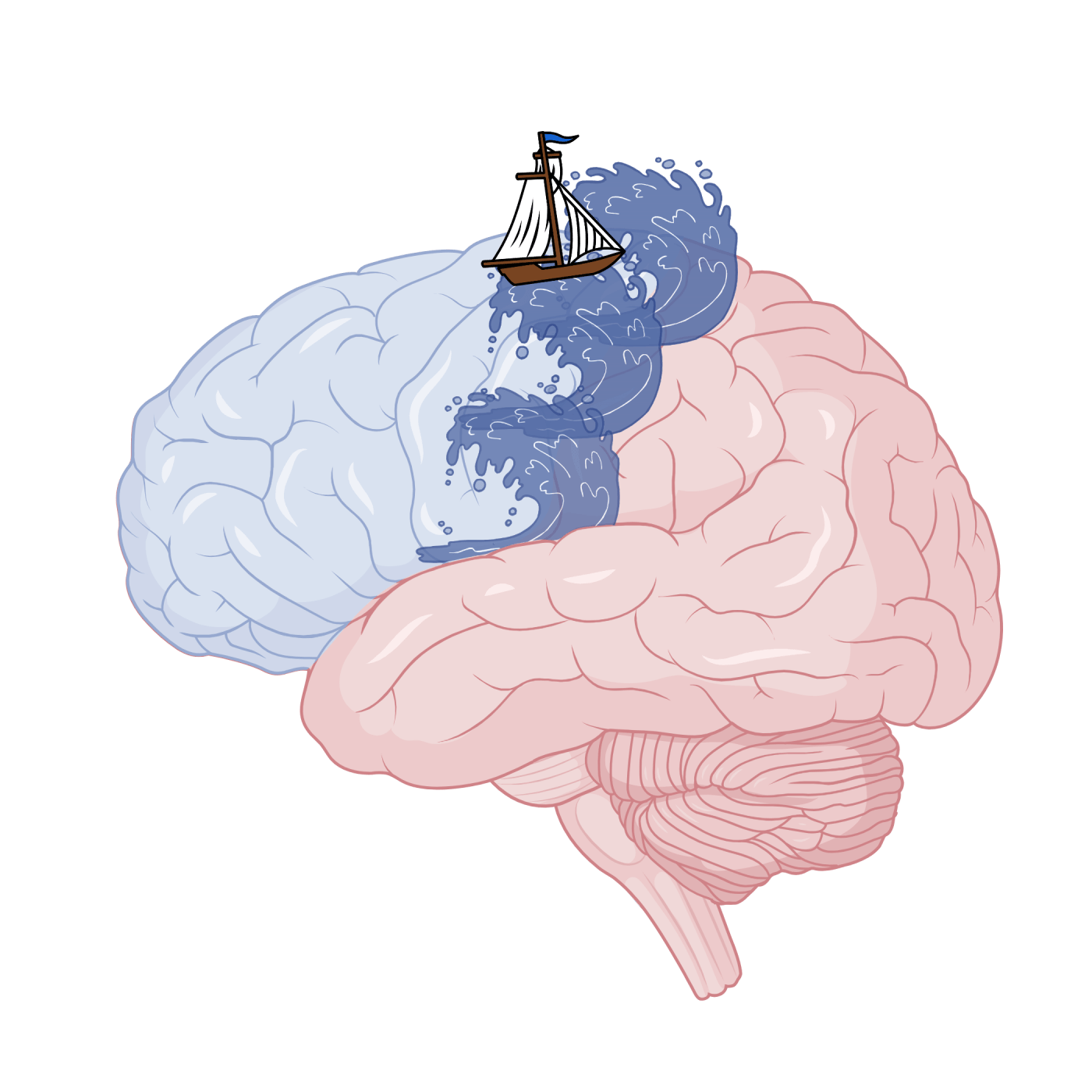

A cortical spreading depolarization (CSD) is a powerful wave of brain activity that slowly spreads across the surface of the brain.1 This wave does not follow along the connections that brain cells generally use to communicate, and it does not obey the boundaries between regions in the brain. It also moves very slowly – much slower than the typical speed at which information travels across the brain.

There is another interesting phase of a CSD that may be important to understanding why CSDs occur. Neurons that become highly active as they are caught up in the wave of the CSD seem to burn themselves out and become silent after the wave has passed. And even though the CSD makes neurons very active for a brief moment, they tend to stay quiet or even silent for a period that lasts much longer than the initial wave.

When do CSDs occur?

CSDs are challenging to measure in humans because they are invisible to the standard tool that doctors use to measure brain waves, the EEG. Additionally, they do not show up on commonly performed brain scans, such as MRIs and CT scans. However, when doctors use special electrodes that can detect CSDs, they have found them to occur under many different circumstances in humans.3

CSDs often occur after the brain has suffered some sort of trauma. An interruption to the blood flow of the brain during a stroke or a bleed in the brain can set off a CSD.4,5 Similarly, CSDs have been detected in most patients that have suffered a head injury.4,6 There is also a strong association between seizures, which are another instance of uncontrolled brain activity, and CSDs.4,7,8 CSDs have been found to occur before, after, and even during seizures.

CSDs may also play a large role in a common, yet extremely painful and perplexing brain condition: migraines. Around 30% of people who suffer from migraines experience an aura, which is a period of time before a migraine starts when a person experiences strange sensations, usually in the form of bright spots or flashes that disturb their vision.4,9 The leading hypothesis about what is happening during a migraine aura is that a migraine is a CSD that slowly spreads across the part of the brain that processes visual information. There are several reasons to believe that auras are indeed CSDs. For example, lab animals that have been engineered to have migraine-causing genes also have frequent CSDs.9,10 Additionally, scientists have also found that it seems to be easier to cause CSDs in female lab animals when compared to male lab animals.10 Similarly, migraines occur at much higher rates in female humans than male humans. Perhaps most strikingly, there is one case in which scientists were able to put a person into a special MRI scanner just before he started to experience a migraine aura (which he induced with his usual trigger of playing basketball for 80 minutes).11 When the person’s migraine aura started, the scientists observed a distinctive signal corresponding with the spread of a CSD in the region of the brain that processes vision.

What happens during a CSD?

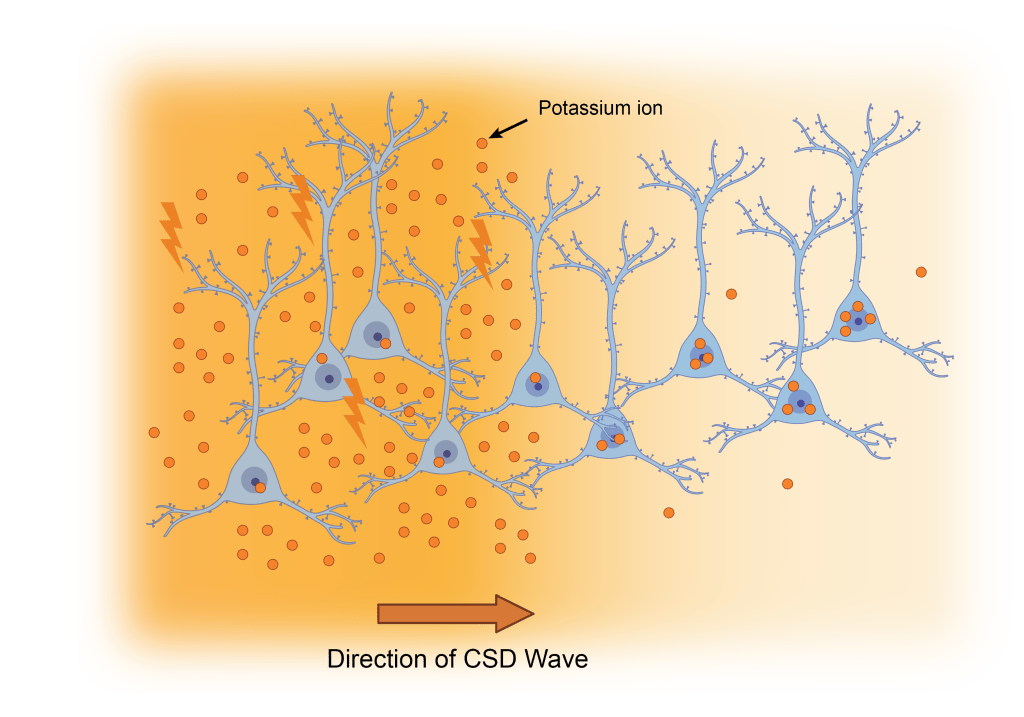

Neurons, which are the primary cell type in the brain, use the language of electrical signals to store information and communicate it to other neurons. To generate these electrical signals, neurons pass positively and negatively charged particles back and forth across their cell membranes (which you can think of as a cell’s skin). When neurons “activate” to send an electrical signal, they need a way to return to their baseline resting state. To do this they rely on one particular charged particle: the potassium ion. Neurons generally like to keep the number of potassium ions inside their membrane much higher than the number of potassium ions outside their membrane. That way, when they want to return to their resting state, they can just open up some channels in their membrane and a few of the potassium ions that they’ve stored will leak outside.

Some evidence suggests that the primary driving force of a CSD are dramatic changes in the amount of potassium ions outside of neurons.1,12 If a neuron opens the channels in its membrane, and there are too many potassium ions outside, none of the potassium ions want to leak out. That means that the neuron becomes highly “active” but cannot return to its resting state. When this happens in many neurons at the same time, it creates a “wave” of simultaneously highly active neurons that travels across the brain.

Though the concentration of potassium and other ions play an important role, there are other major changes that occur during a CSD as well. There is also widespread release of the molecular messengers that neurons use to communicate, as well as significant changes in the blood flow and even swelling of neurons.5,12 And it is still sometimes unclear what is setting off a CSD, and how exactly a CSD stops once it is rolling.

Why do we have CSDs?

Because CSDs are often associated with brain injuries or brain diseases, it has long been assumed that CSDs are something abnormal or harmful to the brain. For example, there is some evidence that CSDs that occur after a stroke expand the area of damage to the brain.4 But, CSDs have been seen in animals ranging from cockroaches, to rabbits, to mice, to humans.12 This means that CSDs have persisted over the long history of evolution, which suggests that they may actually serve an essential or protective function.

Recent evidence suggests that the silencing of brain activity that occurs in the wake of a CSDs may play a role in terminating a seizure or preventing a second seizure from occurring.13 There is also data that a CSD before a brain injury can lessen the damage from the injury. In one study, researchers initiated a CSD in a group of rats up to one week before they suffered a stroke. Rats that were given CSDs before their stroke had significantly less brain cell death during the stroke than rats who did not have a CSD.14 Researchers have also found that CSDs may stimulate the birth of new brain cells.15,16 It is still not clear, however, if these newborn neurons play any role in the brain’s ability to recover or learn new functions after injury.

There is still a great deal for us to learn about these perplexing waves, from their origins to their function in both healthy and injured brains. But if one thing is for certain, it is that CSDs are much more frequent and impactful than many doctors and scientists currently appreciate!

References

1. Kramer, D. R., Fujii, T., Ohiorhenuan, I. & Liu, C. Y. Cortical spreading depolarization: Pathophysiology, implications, and future directions. Journal of Clinical Neuroscience 24, 22–27 (2016).

2. Santos, E. et al. Radial, spiral and reverberating waves of spreading depolarization occur in the gyrencephalic brain. NeuroImage 99, 244–255 (2014).

3. Dreier, J. P. The role of spreading depression, spreading depolarization and spreading ischemia in neurological disease. Nat Med 17, 439–447 (2011).

4. Lauritzen, M. et al. Clinical relevance of cortical spreading depression in neurological disorders: migraine, malignant stroke, subarachnoid and intracranial hemorrhage, and traumatic brain injury. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 31, 17–35 (2011).

5. Ayata, C. & Lauritzen, M. Spreading Depression, Spreading Depolarizations, and the Cerebral Vasculature. Physiol Rev 95, 953–993 (2015).

6. Hartings, J. A. et al. Prognostic Value of Spreading Depolarizations in Patients With Severe Traumatic Brain Injury. JAMA Neurology 77, 489–499 (2020).

7. Aiba, I., Ning, Y. & Noebels, J. L. A hyperthermic seizure unleashes a surge of spreading depolarizations in Scn1a-deficient mice. JCI Insight 8, (2023).

8. Fabricius, M. et al. Association of seizures with cortical spreading depression and peri-infarct depolarisations in the acutely injured human brain. Clin Neurophysiol 119, 1973–1984 (2008).

9. Charles, A. C. & Baca, S. M. Cortical spreading depression and migraine. Nat Rev Neurol 9, 637–644 (2013).

10. Kudo, C., Harriott, A. M., Moskowitz, M. A., Waeber, C. & Ayata, C. Estrogen modulation of cortical spreading depression. The Journal of Headache and Pain 24, 62 (2023).

11. Hadjikhani, N. et al. Mechanisms of migraine aura revealed by functional MRI in human visual cortex. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 98, 4687–4692 (2001).

12. Spong, K. E., Andrew, R. D. & Robertson, R. M. Mechanisms of spreading depolarization in vertebrate and insect central nervous systems. Journal of Neurophysiology 116, 1117–1127 (2016).

13. Tamim, I. et al. Spreading depression as an innate antiseizure mechanism. Nat Commun 12, 2206 (2021).

14. Yanamoto, H., Hashimoto, N., Nagata, I. & Kikuchi, H. Infarct tolerance against temporary focal ischemia following spreading depression in rat brain. Brain Research 784, 239–249 (1998).

15. Urbach, A., Redecker, C. & Witte, O. W. Induction of neurogenesis in the adult dentate gyrus by cortical spreading depression. Stroke 39, 3064–3072 (2008).

16. Yanamoto, H. et al. Induced spreading depression activates persistent neurogenesis in the subventricular zone, generating cells with markers for divided and early committed neurons in the caudate putamen and cortex. Stroke 36, 1544–1550 (2005).

Cover Photo created with biorender.com

Figure 1 made by Sophie Liebergall, Zach Rosenthal, Ethan Goldberg (unpublished data).

Figure 2 adapted from Santos, E. et al. Radial, spiral and reverberating waves of spreading depolarization occur in the gyrencephalic brain. NeuroImage 99, 244–255 (2014). https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Cortical_spreading_depression

Figure 3 created with biorender.com

Leave a comment