September 19th, 2023

Written by: Lindsay Ejoh

Have you ever wondered why there are no perfect drugs on the market to treat any disease? No harmless, side-effect free treatments exist for heart or lung disease, cancers, or brain disorders like PTSD, epilepsy, substance use disorder, sleep disorders or chronic pain. To understand why, it is helpful to know the basic mechanism of how drugs work in the body to fight disease.

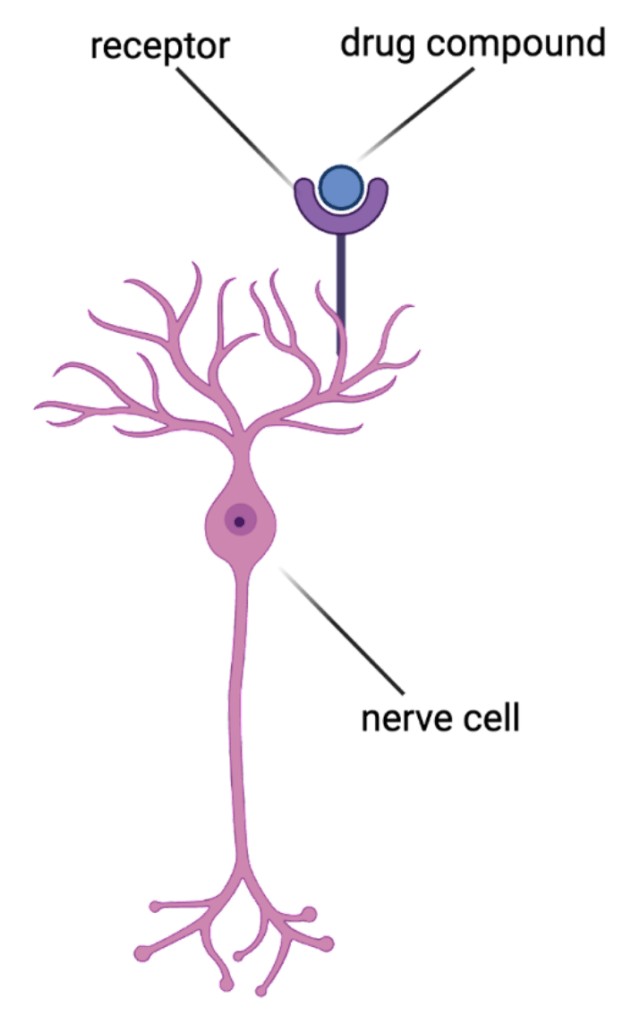

Drug compounds bind to special sites called receptors that are located on or inside of cells.1 They bind to these receptors to change the way that cells function and eventually reduce disease symptoms (Figure 1). Fortunately, a drug will not impact cells that do not have its matching receptor. In theory, this is useful for making sure drugs don’t act where they are not needed. However, many drugs have matching receptors in cells located throughout the body, making it difficult for them to act on a specific, diseased tissue in the body without affecting other tissues.

Let’s consider a specific drug: morphine. This is an opioid drug that is very effective at blocking short-term pain, and works by shutting down the activity of neurons that help process pain2. However, opioid drugs come with very harmful side effects, despite their effective pain-relieving qualities3. This is because opioid receptors are located all over the body- including the gut, liver, testes, ovaries, and the muscles that help you breathe4. Therefore, opioid use can disrupt the functions of these other organs and cause side effects like trouble breathing, constipation, nausea, vomiting, and mood swings. Many opioid receptors can also be found in the parts of the brain that contribute to addiction, leaving users at a higher risk for developing a substance use disorder5.

Morphine isn’t the only drug with these kinds of problems, and millions of people taking pharmaceutical drugs would benefit from drugs that have their intended use without any added unintentional harms. If drugs could target receptors only at the site of the disease, instead of its other receptors in the body, then there would be many fewer side effects.

Fortunately, scientists are developing a new technology that avoids most side effects by targeting drugs to a specific region of the body or the brain. This technology is called chemogenetics6, a type of therapy that treats diseases by reprogramming cells at the site of the issue to produce a “designer receptor” that is created by scientists and isn’t normally found in the body7. This technology takes advantage of the fact that ells can be reprogrammed with the help of viruses. These noninfectious viruses are designed by scientists to insert DNA into cells. A cell takes up this DNA, produces the designer receptor, and is now able to be impacted by a complementary “designer drug” that matches that receptor.

Now, for example, chemogenetics can allow doctors to target the pain-processing neurons that normally express the opioid receptor. Imagine a patient with stomach pain is administered a virus in the stomach, causing the neurons that normally make opioid receptors to produce a receptor of our design8. That designer receptor is matched with a designer drug that can shut the activity of these neurons down, blocking the pain signals in the stomach without affecting opioid receptors on other cells throughout the body9. Because the drug is designed to not bind anywhere in the body except the specific pain-processing region the virus went into, pain relief can occur only at the stomach, without the side effects typically associated with opioid drugs.

So far, chemogenetics research has been conducted in animals, but some companies are working toward expanding this for human use. Currently, chemogenetic drugs aren’t perfect either. They can also cause side effects due to the fact that these compounds eventually break down into smaller molecules that can bind to unwanted receptors in the body, which brings us back to our original problem of unwanted side effects. Therefore, more research must be conducted to produce the safest designer drugs, designer receptors and viruses for human use10. A world without drug side effects seems so close yet so far, but I believe that a future where we can help people get treatment for their diseases and conditions without compromising their general well-being is worth the fight.

References

- Salahudeen, M. S., & Nishtala, P. S. (2017). An overview of pharmacodynamic modelling, ligand-binding approach and its application in clinical practice. Saudi pharmaceutical journal : SPJ : the official publication of the Saudi Pharmaceutical Society, 25(2), 165–175. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsps.2016.07.002

- Listos, J., Łupina, M., Talarek, S., Mazur, A., Orzelska-Górka, J., & Kotlińska, J. (2019). The Mechanisms Involved in Morphine Addiction: An Overview. International journal of molecular sciences, 20(17), 4302. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms20174302

- A. (n.d.). What is the U.S. opioid epidemic? Retrieved March 09, 2021, from https://www.hhs.gov/opioids/about-the-epidemic/index.html

- Sobczak, M., Sałaga, M., Storr, M. A., & Fichna, J. (2014). Physiology, signaling, and pharmacology of opioid receptors and their ligands in the gastrointestinal tract: current concepts and future perspectives. Journal of gastroenterology, 49(1), 24–45. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00535-013-0753-x

- Corder, G., Castro, D. C., Bruchas, M. R., & Scherrer, G. (2018). Endogenous and exogenous opioids in pain. Annual Review of Neuroscience, 41(1), 453-473. doi:10.1146/annurev-neuro-080317-061522

- Campbell, E. J., & Marchant, N. J. (2018). The use of chemogenetics in behavioural neuroscience: receptor variants, targeting approaches and caveats. British journal of pharmacology, 175(7), 994–1003. https://doi.org/10.1111/bph.14146

- Scheller, E. L., & Krebsbach, P. H. (2009). Gene therapy: design and prospects for craniofacial regeneration. Journal of dental research, 88(7), 585–596. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022034509337480

- Qi, Y., Nelson, T. S., Prasoon, P., Norris, C., & Taylor, B. K. (2023). Contribution of µ opioid receptor-expressing dorsal horn interneurons to neuropathic pain-like behavior in mice. Anesthesiology, 10.1097/ALN.0000000000004735. Advance online publication. https://doi.org/10.1097/ALN.0000000000004735

- Thomas, Dr. L. (2019, February 6). What are dreadds?. News. https://www.news-medical.net/life-sciences/What-are-DREADDs.aspx#:~:text=%22Designer%20Receptors%20Activated%20Only%20by,cell%20activity%20in%20ambulatory%20animals.

- Manvich, D. F., Webster, K. A., Foster, S. L., Farrell, M. S., Ritchie, J. C., Porter, J. H., & Weinshenker, D. (2018). The DREADD agonist clozapine N-oxide (CNO) is reverse-metabolized to clozapine and produces clozapine-like interoceptive stimulus effects in rats and mice. Scientific reports, 8(1), 3840. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-018-22116-z

Cover image from Pixabay by mcmurryjulie

Figure 1 made in BioRender by Lindsay Ejoh

Leave a comment