September 12th, 2023

Written by: Kara McGaughey

You’ve probably laughed your way through one of the many collections of people who look just like their dogs, delighting in the surprising similarities between pets and their owners. While obviously staged, it’s undeniably fun to brush aside the fact that your version of a luxurious coat hangs in your closet and imagine you and your pet moving through the world as one and the same. What if you and your furry friend had more in common than you think? What if these similarities could impact human health and disease? In this post, we will compare and contrast how you and your dog perceive the world and explore how basic similarities between human and canine visual system function and dysfunction are helping researchers find a cure for blindness.

How do your eyes compare to your dog’s?

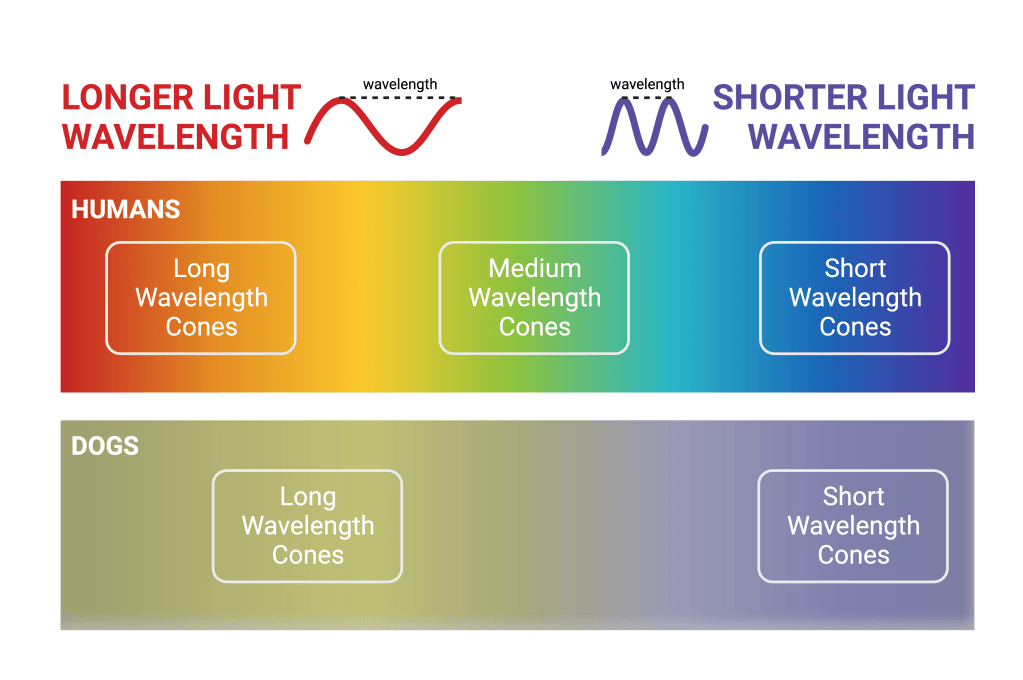

As you read this sentence, the light from your screen passes through the air and into your eyes. It continues traveling until it reaches the very back of your eyeballs (called the retina) where it makes contact with two kinds of light-absorbing cells: rods and cones.1 Rods, which are more sensitive to incoming light than cones, help us operate in dimly-lit conditions. When you tip-toe to the kitchen in the middle of the night, it’s your rods that help you distinguish the dark outlines of any obstacles in your way. As you tug the refrigerator open and its bright light floods the room, your cones, which require more light than rods and enable color vision, kick in. Suddenly, your blue pajama pants and red slippers transform, shedding shades of gray for their rightful color hues. Your pajamas and your slippers appear as these different colors because they reflect different wavelengths of light. Humans have three cone types in order to facilitate color detection across the range of visible light wavelengths.1,2 Long wavelength cones are most sensitive to longer wavelengths of light that appear red, orange, and yellow (Fig. 1). Medium wavelength cones are most sensitive to light that appears green and short wavelength cones support our perception of darker blues and purples.

In the last few decades, research into the anatomy and function of canine eyes has allowed us to more fully compare and contrast their visual machinery with ours. Like humans, dogs have both rods and cones.3 However, the proportion of these cell types is a bit different. Because dogs evolved as nocturnal hunters, their eyes are much better adapted to see well in the dark and they have many more rods than cones compared to humans.3 Having more rods to support vision in dimly-lit environments explains why your pup can much more easily navigate around your bedroom in the dark and doesn’t mind eating with the lights off.

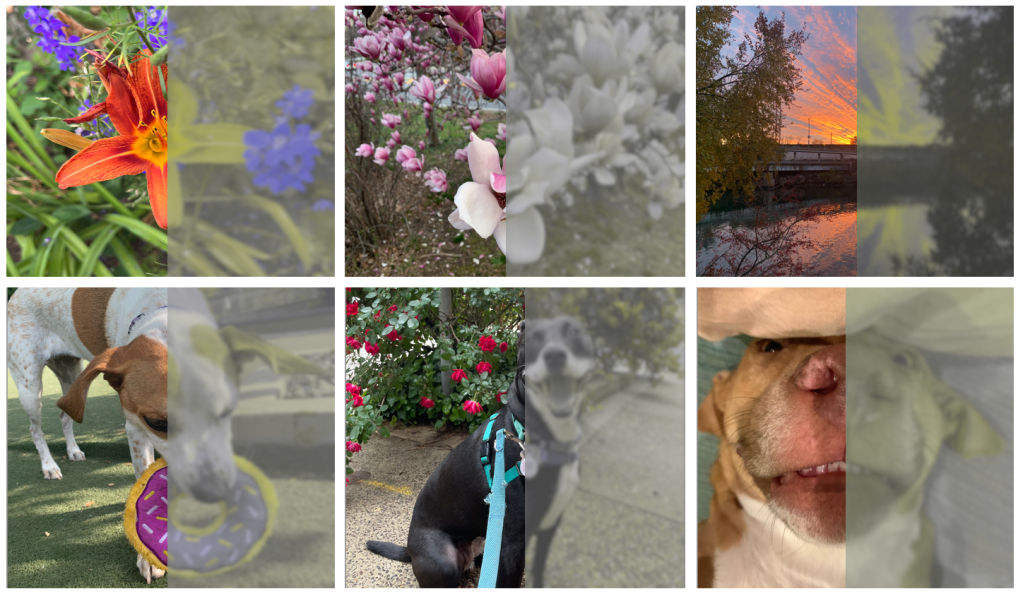

Another big difference between the canine and human visual systems is the number of cone types. Unlike humans and their three cones, dogs have only two cone types: long and short wavelength.3 Since the colors we perceive entirely depend on the combination of light wavelengths registered by cones, the world looks quite different to dogs whose cones register predominantly yellows, blues, and purples (Fig. 1). However, it’s important to know that just because dogs can’t perceive particular colors doesn’t mean that they can’t see objects with those colors. Rather, it means that while your blues and purples will look much the same to your furry friend, reds and greens become a yellowish gray-brown (Fig. 2). If your dog enjoys playing fetch, perhaps you’ve noticed it takes them longer to find and retrieve red and green balls. It’s likely not for lack of trying, and simply because their color vision causes the ball to fade into its surroundings.

While humans and dogs have different numbers of cone types that support different color experiences, their cones are distributed across the retina in a similar manner. In humans, nearly all cones are located in a central area of the retina called the fovea.1 The fovea is where our vision is sharpest. It corresponds to the center of gaze that we direct towards the objects of our attention, and it is what enables us to take in rich visual detail. Considered a visual feature unique to primates, other animals do not have a fovea. Although it is not technically a fovea, dogs, like primates, do have a majority of their cones packed tightly into a central point in their retina.4 “When we think about our vision and what’s important about our vision, it’s the fovea,” says Geoffrey Aguirre, a professor in the Neurology Department at the University of Pennsylvania. “A principle idea of human and primate vision is that we’ve got this fovea. Everything else is built around that.” Having a fovea-like structure means that dog vision is a lot more like human vision than originally thought.

How can dogs help us better understand the human visual system?

With many features of their visual systems in common, humans and dogs share many of the same types of genetic retinal diseases and present with many of the same symptoms.5 However, since dogs are inbred, retinal diseases that are rare in humans crop up more frequently. Additionally, different genetic mutations tend to occur in different dog breeds, making them excellent, naturally-occuring models of (or animals in which to study) different retinal diseases.5

William Beltran and Gustavo Aguirre, veterinary ophthalmologists and vision scientists at the University of Pennsylvania, run a research program that leverages these dog models to develop therapies that are ultimately used to cure disease in humans. The pair and their collaborators have studied more than 20 naturally-occurring canine retinal diseases that are similar to retinal diseases found in humans, including retinitis pigmentosa (progressive degeneration of the retina) and Leber congenital amaurosis, or LCA (progressive vision loss).6 For each retinal disease, the group is designing gene therapies that target its specific genetic mutation. Their efforts have led to an FDA-approved treatment for children and adults with LCA, an inherited form of vision loss that progresses towards complete blindness.7,8 This treatment is the first prescription gene therapy product to help patients with inherited retinal disease, and it requires just a single dose. While this is an incredible accomplishment in its own right, there are three more potential therapies in active clinical trials.6To design and refine these gene therapies, the group measures how they affect brain function using functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI). Geoffrey Aguirre, a neurologist at the University of Pennsylvania who specializes in this kind of brain imaging, takes precise measurements of activity in canine visual areas before and after treatment. “We’ve shown that in dogs with inherited retinal diseases that cause blindness, if you give them the gene therapy, you can restore responses to light in the brain,” says Aguirre. Ultimately, he wants to use brain imaging to push for gene therapy treatments that can recover not just responses to light, but also responses to color. Using yellow and blue light presented to healthy dogs, Aguirre has shown that he’s able to elicit and measure brain responses to light and activity in brain areas responsible for color vision. “In dogs with inherited retinal diseases, both these responses are gone,” Aguirre says. “Next step is to treat them, measure again, and see if we can recover the responses.”

While they are yielding exciting results, making these kinds of measurements is incredibly technically challenging. For one, the equipment required for these brain scans isn’t designed for dogs. Aguirre uses a piece of the MRI machine built to scan the human knee. Getting these scans, or snapshots, of activity in visual areas is further complicated by the dog brain’s small size. “What you see around the dog head is all muscle,” says Aguirre. “Then you have a thick skull. And then you get to a brain that is — best case — the size of a lemon.” Nevertheless, Aguirre has successfully scanned enough animals to create and compile a detailed anatomical map of the dog brain that has been downloaded and used by groups around the world.9

Aguirre also works applying many of these same measurement techniques to human subjects and their brains. We are able to take and transfer what we learn about function and dysfunction in the dog visual system to the human visual system (a process scientists call “translation”) because “dogs make great large-animal models for vision,” Aguirre says. In addition to providing insight into the perception of lower-level visual features, like light and color, ongoing work shows that dogs also have much more advanced visual capabilities, like face perception. Researchers at Emory University have used fMRI to measure the dog brain response to human faces and dog faces vs. everyday objects. They found that dogs, like humans, have a part of the brain that responds preferentially to faces.10 This to say, it’s becoming increasingly apparent that — despite our differences — dogs and their visual systems open up the door to translational vision science. “You really have to grapple with questions like: What is it that dogs can see? What is the organization of the canine visual system?” says Aguirre. “But we can apply that understanding to critical questions that are relevant for clinicians.”

So, the next time you notice your dog exploring the world, hopefully you can appreciate that while their perception of the world might be colored a bit differently, the basic structural and functional details of your visual systems have more in common than meets the eye. In fact, the key to understanding and treating blindness might be peacefully sleeping near your feet.

Interested in reading more? Check out our PNK archives for additional information on color perception, the amazing (visual and cognitive) capabilities of dogs, and how other animals, like praying mantids, can help us make sense of the visual system, too.

References

- Kandel E.R., & Schwartz J.H., & Jessell T.M., & Siegelbaum S.A., & Hudspeth A.J., & Mack S., (2014). Principles of Neural Science, Fifth Edition. McGraw Hill. https://neurology.mhmedical.com/content.aspx?bookid=1049§ionid=59138139

- Lamb, T. D. (2016). Why rods and cones? Eye, 30(2). https://doi.org/10.1038/eye.2015.236

- Byosiere, S.-E., Chouinard, P. A., Howell, T. J., & Bennett, P. C. (2018). What do dogs (Canis familiaris) see? A review of vision in dogs and implications for cognition research. Psychonomic Bulletin & Review, 25(5), 1798–1813. https://doi.org/10.3758/s13423-017-1404-7

- Beltran, W. A., Cideciyan, A. V., Guziewicz, K. E., Iwabe, S., Swider, M., Scott, E. M., Savina, S. V., Ruthel, G., Stefano, F., Zhang, L., Zorger, R., Sumaroka, A., Jacobson, S. G., & Aguirre, G. D. (2014). Canine retina has a primate fovea-like bouquet of cone photoreceptors which is affected by inherited macular degenerations. PloS One, 9(3), e90390. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0090390

- Miyadera, K., Acland, G. M., & Aguirre, G. D. (2012). Genetic and phenotypic variations of inherited retinal diseases in dogs: The power of within- and across-breed studies. Mammalian Genome, 23(1), 40–61. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00335-011-9361-3

- PennVet Division of Experimental Retinal Therapies. (n.d.). Our research. PennVet.com. https://www.vet.upenn.edu/research/centers-laboratories/research-laboratory/experimental-retinal-therapies/our-research

- Fischer, A. (2017, December 18). FDA approves novel gene therapy to treat patients with a rare form of inherited vision loss. FDA News Release. https://www.fda.gov/news-events/press-announcements/fda-approves-novel-gene-therapy-treat-patients-rare-form-inherited-vision-loss

- Aguirre, G. K., Komáromy, A. M., Cideciyan, A. V., Brainard, D. H., Aleman, T. S., Roman, A. J., Avants, B. B., Gee, J. C., Korczykowski, M., Hauswirth, W. W., Acland, G. M., Aguirre, G. D., & Aguirre, G. K. (2007). Canine and Human Visual Cortex Intact and Responsive Despite Early Retinal Blindness from RPE65 Mutation. PLoS Medicine, 4(6), e230. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.0040230

- Datta, R., Lee, J., Duda, J., Avants, B. B., Vite, C. H., Tseng, B., Gee, J. C., Aguirre, G. D., & Aguirre, G. K. (2012). A Digital Atlas of the Dog Brain. PLOS ONE, 7(12), e52140. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0052140

- Dilks, D. D., Cook, P., Weiller, S. K., Berns, H. P., Spivak, M., & Berns, G. S. (2015). Awake fMRI reveals a specialized region in dog temporal cortex for face processing. PeerJ, 3, e1115. https://doi.org/10.7717/peerj.1115

Cover Photo by Ruby Schmank on Unsplash

Figure 1 made with BioRender.com.

Figure 2 photos taken by Kara McGaughey and processed with DogVision.

Figure 3 shared with permission of Dr. Geoffrey Aguirre.

His name is Gustavo Aguirre

LikeLike