August 29th, 2023

Written by: Joe Stucynski

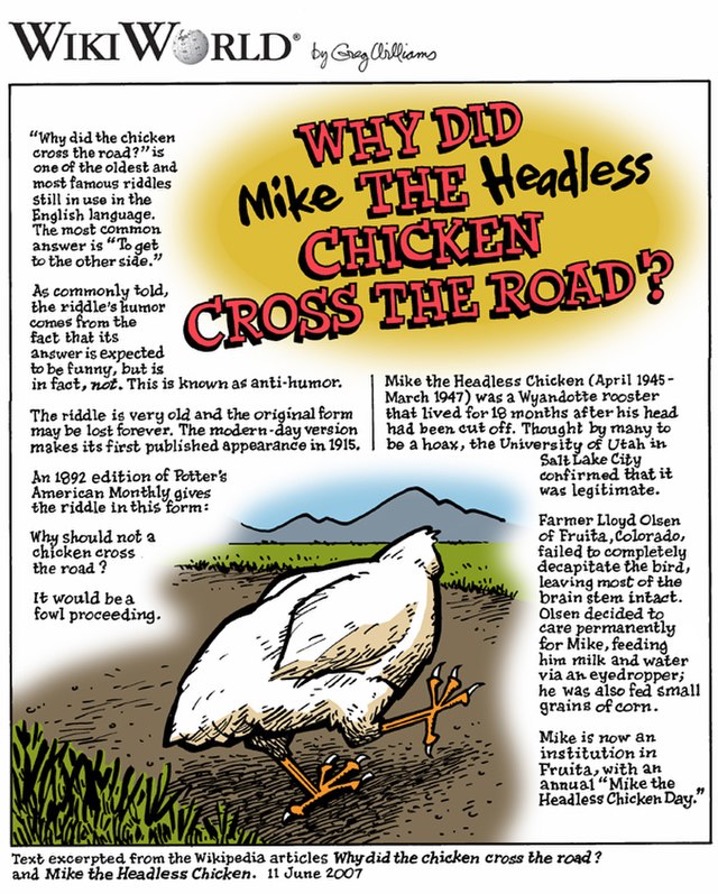

If you’ve ever heard the expression ‘running around like a chicken with its head cut off,’ you may have stopped to wonder if that is even possible. As it turns out, after being beheaded in the process of becoming someone’s dinner, chickens can sometimes move or walk briefly without a head brain. As bewildering as that sounds, there is one famously documented case of a chicken cheating death and continuing to live a surprisingly normal life without a head. Yes, you read that right… Mike the Headless Chicken became a nationally famous sideshow attraction in 1945, living for more than a full year after his encounter with a poorly aimed swing of the axe.1 Despite his grisly fate, the reason for Mike’s survival reveals striking insights into how the brain is organized, and parallels many of the early findings in humans that contributed to the birth of modern neuroscience.

Why Mike survived

In Mike’s case, when his head was chopped off, the very back of his brain remained attached to his body, including an area called the brainstem. As a result, he was reportedly still able to breathe, walk normally, and even attempt behaviors including pecking and cleaning.1 This is because many of the brain functions that support life and basic movements are controlled by neurons in the back of the brain. These vital functions can include breathing rate, heart rate, blood pressure, sleep, hunger, thirst, touch, and even pain. Furthermore, important movement behaviors such as walking or pecking are considered similar to reflex movements in that they do not require conscious thought to control. Reflex mechanisms can include neural circuits called central-pattern generators, such as those that control walking. In humans and chickens, the central pattern generator for walking is located purely in the spinal cord, so Mike’s intact spinal cord still allowed him to walk. While Mike couldn’t perform more complex actions like navigating around chicken coop or interacting with other animals, the set of actions he could perform based on those remaining spinal cord and brainstem central pattern generators allowed him to get along just fine.

The brainstem – anatomy, history, and why it’s worth studying

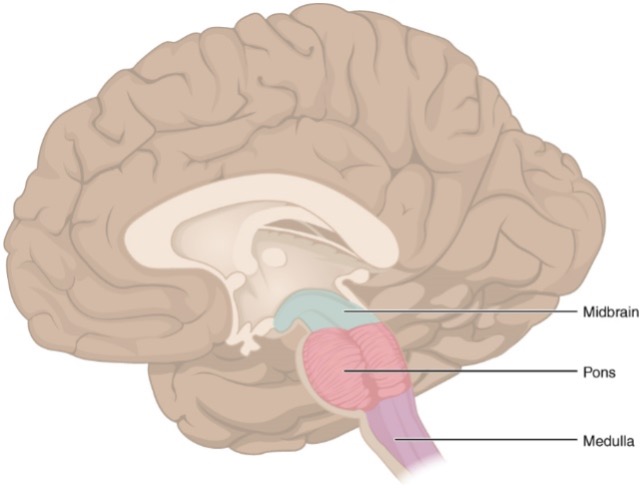

The brainstem is composed of 3 main areas: the medulla, the pons and midbrain, which sit at the base of the skull and function as the first stop in the brain from the spinal cord. Evolutionarily speaking, the brainstem is considered the oldest section of the brain since it developed first to conduct the necessary processes that support life.2 As nervous systems evolved to become more complex, new systems and functions developed on top of the brainstem including the parts of the brain involved in regulating emotions, planning, and complex thought.

Because most animals share many functions and behaviors that support life, like breathing and eating, the brainstem is an attractive area for neuroscientists to study. By understanding how the brainstem controls these vital functions in other animals, and because the organization of the brainstem has not changed significantly over the course of evolution, we can learn a great deal about how it controls vital functions in humans.

While the brainstem is much smaller than most other brain areas, it packs a lot of vital functions into its neurons. The brainstem contains many small but distinct populations of neurons that are highly intermingled with each other.2 Accessing and distinguishing these small populations can be challenging for neuroscientists attempting to understand their functions. Furthermore, because so many bodily processes are closely linked, the neurons in the brainstem often pull double-duty and help control more than one function. As an example, a recent study found that neurons in the lower part of the brainstem that help control blood pressure can also control sleep, and help regulate blood pressure differently during sleep versus wakefulness.3 This finding helps shed some light on why some patients experiencing heart disease can have different symptoms when they’re asleep compared to when they’re awake, and points to the complex role of medulla neurons in the control of blood pressure.

Missing, damaged, or inhibited brain areas can give clues to their function

The tale of Mike also supports one of the main tenants of modern neuroscience – that structure dictates function. In this case, most chickens lost their brainstem and died, but Mike’s brainstem was kept intact and he survived. Therefore, the brainstem is vital for sustaining life. Similar tales played out in early neuroscience that gave clues to which brain areas did what. In one famous example, a railroad worker named Phineas Gage experienced a catastrophic injury in which a railway spike lodged into the front part of his brain.4 Phineas survived but had a noticeably different personality afterwards, as well as an inability to control his anger, and trouble making rational decisions. This led scientists to believe that the frontal lobe of the brain contains areas important for emotional thought and decision making, which later experiments confirmed.

Following the same logic, neuroscientists often deliberately turn off areas of the brain to assess what they do. One such method is called Transcranial Magnetic Stimulation (TMS),5 in which an electromagnetic coil can temporarily disrupt the activity of neurons in the targeted brain region when it’s turned on. When the magnetic field is turned off, brain function returns to normal with no injury whatsoever, and decades of research have proven TMS to be a safe and effective way of reversibly turning off brain areas in humans.5 If, for instance, you momentarily disrupt areas in the temporal lobe, the person may momentarily be unable to speak. One conclusion would then be that the temporal lobe contains brain areas that control language or the ability to speak. This strategy has been extrapolated much further and is regularly used by neuroscientists to ask whether certain neural circuits, or even specific types of neurons, are necessary for certain behaviors. If you turn off some specific neurons in the brain and it affects behavior, then those neurons must be related to that behavior in some way.

All in all, while Mike may be famous enough to have his own festival in his hometown, neuroscientists remember him for teaching us important lessons about the vital nature of the brainstem. Your thoughts and feelings may reside elsewhere in the brain, but your life support system lives in the brainstem. And while there is still a lot to learn about how this area of the brain helps control all of the complexities of the body, it’s always good to remember what we know now because of the legendary Mike.

References

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mike_the_Headless_Chicken

- Angeles Fernández-Gil M, Palacios-Bote R, Leo-Barahona M, Mora-Encinas JP. Anatomy of the brainstem: a gaze into the stem of life. Semin Ultrasound CT MR. 2010 Jun;31(3):196-219. doi: 10.1053/j.sult.2010.03.006. PMID: 20483389.

- Yao Y, Barger Z, Saffari Doost M, Tso CF, Darmohray D, Silverman D, Liu D, Ma C, Cetin A, Yao S, Zeng H, Dan Y. Cardiovascular baroreflex circuit moonlights in sleep control. Neuron. 2022 Dec 7;110(23):3986-3999.e6. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2022.08.027. Epub 2022 Sep 27. PMID: 36170850.

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Phineas_Gage

- Hallett M. Transcranial magnetic stimulation: a primer. Neuron. 2007 Jul 19;55(2):187-99. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2007.06.026. PMID: 17640522.

Cover Photo by Thomas Iversen on Unsplash

Figures from Wikimedia Commons:

Figure 1 by Greg Williams on Wikimedia Commons

Figure 2 by OpenStax on Wikimedia Commons