July 18th, 2023

Written by: Julia Riley

Have you ever watched a movie where a character’s thoughts are conveyed in a voiceover? Had spirited arguments with yourself in the shower? How about frantically reciting facts in your mind right before an exam so that they don’t have a chance to slip away?

Representations of inner speech are widespread in pop culture; it is a mental tool that we frequently use in everyday life. Neuroscientists have begun to uncover how people are capable of silently consulting themselves, how this might look different from person to person, and ways that people can leverage inner speech to better their lives.

How the brain talks to itself

In order to understand how our brains talk to themselves, we need to understand the significance of the different “regions” of the brain. The brain is segregated into spatial regions. Each region of your brain contains a group of cells that become active when you are trying to accomplish something, and different regions can collaborate to help you accomplish a task.

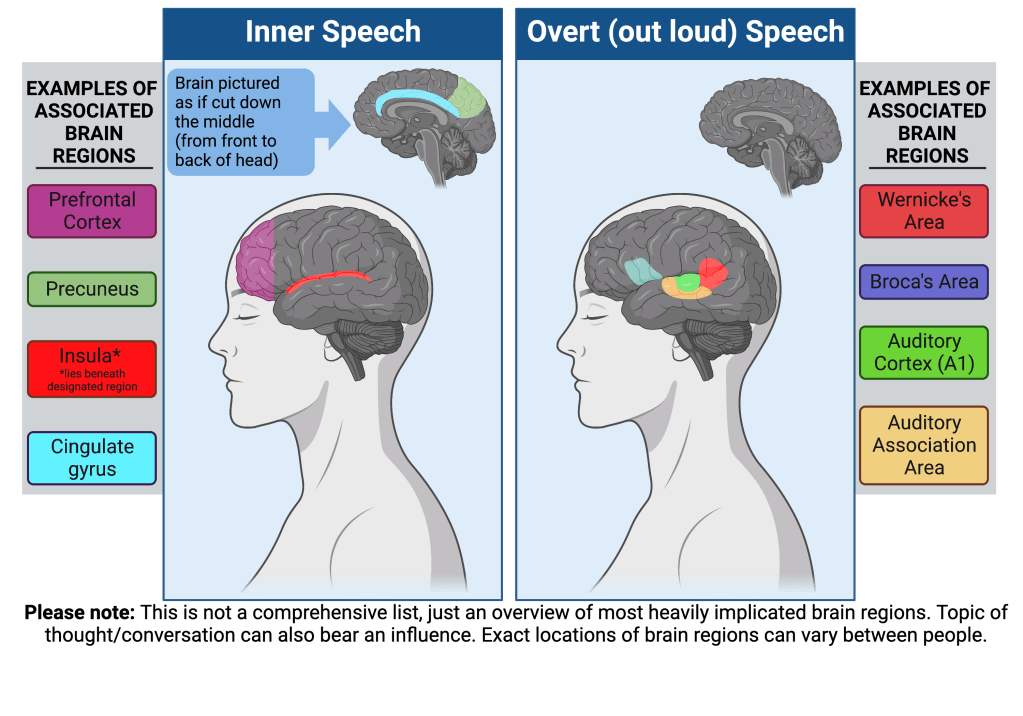

We have known for some time that there are several regions of the brain that give us the ability to speak out loud, also called overt speech1. You might expect that the areas of the brain that contribute to overt speech would be the same as those that control inner speech. Surprisingly, this is not necessarily the case (Figure 1). If overt and inner speech were produced by the exact same brain regions, then an inability to speak out loud would also mean an absent inner voice. Instead, researchers have found that people who have various forms of severe speaking disabilities, which are broadly named aphasias, often have active and functional inner speech. However, this is not a two-way street. Although people that cannot fluently speak out loud often retain their inner voice, people who struggle to produce an inner voice typically also have difficulties speaking out loud2. This leads us to a puzzling question- why would a brain that cannot coordinate overt speech be able to produce inner speech?

Currently, scientists think this might be because the brain regions that are major players in inner speech production are different from the brain regions involved in producing overt speech. We have yet to understand all the brain regions involved in creating inner speech. We do know of several smaller regions within a larger brain area that can participate. This larger brain area lies right behind your forehead and is called the prefrontal cortex. The prefrontal cortex is involved in intricate thought processes, like planning or learning. There is an area of the prefrontal cortex that becomes active when contemplating information about people, and another that is active when trying to regulate your emotions (for example, calming yourself down when upset). These areas are especially active during inner speech3. While we know that some brain regions tend to be particularly active participants in creating inner speech, there is no set cast list of brain regions involved in this production. Topic of thought likely plays a role in which regions participate; for example, we know that different brain regions can become active depending on whether you are reflecting on your own life or thinking about another person3.

Just as there are certain brain regions that become active to facilitate inner speech, there are others responsible for helping your brain make the distinction between the inner speech that you “hear” in your mind and speech that you actually hear coming from other people4,5. This ability to distinguish your actions from the actions of others is a phenomenon called corollary discharge. Corollary discharge occurs in a multitude of scenarios, including helping you recognize inner speech as your own thoughts 4,5. This is important because a particularly devastating symptom of some mental health disorders are auditory hallucinations, which are sometimes referred to as “hearing voices”. There is some evidence that these hallucinations occur when the brain fails to recognize one’s inner speech as their own4. If we can understand the teamwork happening between brain regions that allows us to produce inner speech and properly identify it as our own thoughts, it might help us understand why auditory hallucinations occur, and eventually lead to the development of additional methods for preventing them.

The different flavors of inner speech

Everyone likely has some method of communicating with themselves- it just doesn’t look the same for everyone! While inner speech that you can “hear” like a voice in your mind is likely the most common way people communicate with themselves, it is far from the only way. For example, someone who was born deaf might not hear an inner voice. Instead, they might picture words or sign language6.

This might make it seem like the way we choose to communicate with ourselves is as simple as switching on and off an inner voice, whatever that may look like for you. However, this is not true to life; the way we choose to communicate with ourselves is likely more nuanced. We might all have multiple “languages” that we use for inner speech, whose use depends on the scenario in which we find ourselves. Possibly the clearest example of this is inner speech in people who have near-fluent command of more than one language. While people who are multilingual are often capable of thinking in all the languages they know, they are far more likely to think in their native language7, especially if their thought process entails attempting to understand a complicated situation8,9.

Using inner speech to your advantage

Have you ever had someone come to you in the throes of a highly emotional situation to ask for advice? You probably had a more logical perspective than they did- it’s easier to be reasonable when you’re removed from an emotionally charged situation. Research shows that people can gain a similar perspective on situations in their own lives by referring to themselves in the third person (using your name to refer to yourself in your own thoughts, rather than “I”)8. By tricking your brain into thinking of yourself as if you were someone else, you see things more objectively10. This is effective in promoting tranquility and combatting impulsive decision making during emotionally fraught situations. It is also a method of trying to control your emotions that is very different from trying to force a sudden change in the nature of your thoughts. For example, if you were worried about taking a test, you could use this method to ask yourself what you can do to help your chances of success, rather than simply forcibly telling yourself to stop worrying.

Some scientists think that this may end up being especially relevant in helping people who struggle to control the amount of time that they spend either submerged in their negative emotions or mentally replaying the life events surrounding them. This pattern of thinking is very common in people with depression, which affects approximately 21 million adults in the U.S per year11 – that’s equal to almost 2.5x the population of New York City. This could also be a useful coping mechanism for children, who may have yet to develop impulse control and tend to have a lower tolerance for emotional discomfort than adults. Many children intuitively use this strategy by talking out loud to themselves to work through confusing or overwhelming situations8.

So, the next time you’re stressed about something, try forcing your brain to ask itself more about what’s going on- you might be pleasantly surprised with the outcome!

References

- UCSF Memory and Aging Center. (2023). Speech and Language Symptoms. Memory & Aging Center, University of California, San Francisco. Retrieved from https://memory.ucsf.edu/symptoms/speech-language

- Fama ME, Turkeltaub PE. Inner Speech in Aphasia: Current Evidence, Clinical Implications, and Future Directions. Am J Speech Lang Pathol. 2020 Feb 21;29(1S):560-573. doi: 10.1044/2019_AJSLP-CAC48-18-0212. Epub 2019 Sep 13. PMID: 31518502; PMCID: PMC7233112.

- Araujo, H. F., Kaplan, J., & Damasio, A. (2013). Cortical midline structures and autobiographical-self processes: an activation-likelihood estimation meta-analysis. Frontiers in human neuroscience, 7, 548. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnhum.2013.00548.

- Jack, B. N., Le Pelley, M. E., Han, N., Harris, A. W. F., Spencer, K. M., & Whitford, T. J. (2019). Inner speech is accompanied by a temporally-precise and content-specific corollary discharge. NeuroImage, 198, 170–180. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuroimage.2019.04.038.

- Ford, J. M., Roach, B. J., & Mathalon, D. H. (2010). Assessing corollary discharge in humans using noninvasive neurophysiological methods. Nature protocols, 5(6), 1160-1168.

- Bellugi, U., Klima, E. S., & Siple, P. (1974). Remembering in signs. Cognition, 3(2), 93-125.

- Pia Resnik (2021) Multilinguals’ use of L1 and L2 inner speech, International Journal of Bilingual Education and Bilingualism, 24:1, 72-90, DOI: 10.1080/13670050.2018.1445195

- “Inner Monologues with Ethan Kross, PhD.”Speaking of Psychology, Spotify. 3/5/2020.

- Panayiotou, A. (2004). Switching codes, switching code: Bilinguals’ emotional responses in English and Greek. Journal of multilingual and multicultural development, 25(2-3), 124-139.

- Orvell, A., & Kross, E. (2019). How self-talk promotes self-regulation: Implications for coping with emotional pain. In S. C. Rudert, R. Greifeneder, & K. D. Williams (Eds.), Current directions in ostracism, social exclusion, and rejection research (pp. 82–99). Routledge/Taylor & Francis Group. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781351255912-6

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. (n.d.). Major depression. National Institute of Mental Health. https://www.nimh.nih.gov/health/statistics/major-depression.

Figure 1 created by Julia Riley on BioRender.

Cover Photo adapted from an image created by balintseby on Freepik.